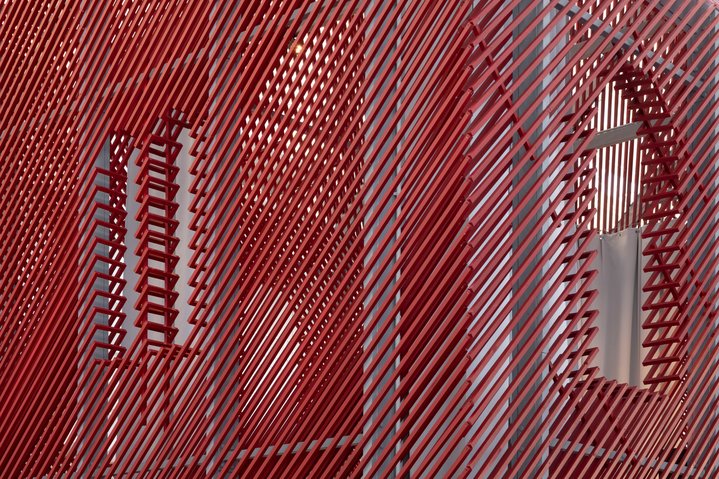

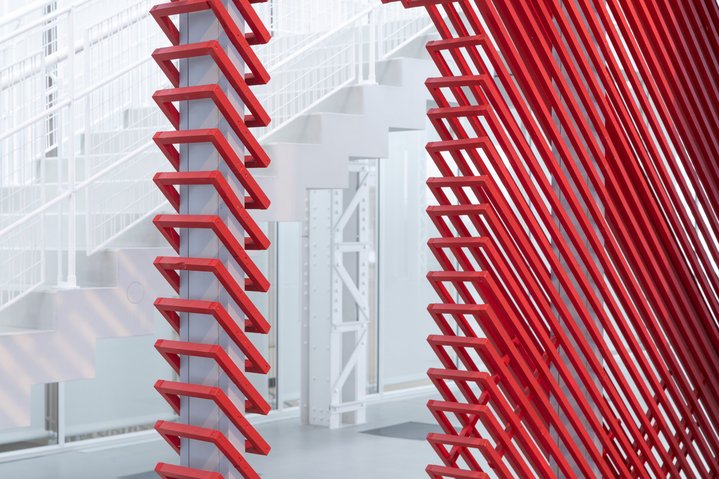

Alexander Konstantinov. House of Air and Lines. GES-2 House of Culture, Moscow, 2024. Photo by Daniil Annenkov. Courtesy of GES-2 House of Culture

Post-Minimal Art of Alexander Konstantinov on view in Moscow

GES-2 House of Culture and the State Tretyakov Gallery have joined forces to pay homage to the late artist Alexander Konstantinov.

Alexander Konstantinov (1953–2019) is hero of the hour both at the Tretyakov Gallery and GES-2 in a rare example of synergy between Moscow’s top museum of Russian art and the nation’s largest privately funded art institution which is developing contemporary art in Russia. The Tretyakov Gallery is showing sculptures, objects and works on paper created by the artist over more than three decades, from 1984 to 2019. In GES-2, two architectural objects, one of which was created in Austria in 2008 and the other in the United States in 2011, are re-created based on the artist's designs.

Konstantinov was an artist with a mathematical eye. This rather rare talent is a physical and even physiological tool of an artist: the ability to draw a perfectly straight line and the gift of accurately dividing a surface into equal parts. He turned this natural capacity into his main means of artistic expression.

In the Moscow art world, Konstantinov’s brand has affectionately become known as millimetrovki, which are ungraphed technical papers reproduced, scaled and modified by hand (although strictly speaking he made various different series all of which have different names, such as ‘Millimetrovki’, ‘Formulary’, or ‘Scales’). There is a simple charm of his even lines and repeating grids, and this distinguishes his work from those of his generation. It is hard not to see in his art a reflection of his first profession – a mathematician.

He is a rare example of a ‘maths professor with a passion for drawing’ who gradually became an ‘artist for artists’. Konstantinov was a full-time professor of applied mathematics, a Doctor of Mathematical Sciences, and never received any formal training as an artist. Throughout his career, he gained in recognition in part because he fitted in the underground artist circles. Artists such as Alexander Ponomarev (b. 1957), Francisco Infante-Arana (b. 1943), Vladimir Kupriyanov (1954–2011), and Vladimir Nasedkin (b. 1954) saw in him a member of their own ‘tribe’, a subtle master with his own vision.

This vision places Konstantinov as post-minimalist artist, a movement which was relatively exclusive in Russia. The first Russian post-minimalists were graphic artists who switched from works on paper to large forms: Alexander Yulikov (b. 1943), a graduate of the Moscow Polygraphic Institute, and William Bruy (b. 1946), a printer at the Experimental Workshop of the Leningrad Union of Artists. Konstantinov found his own path, independently, and gradually moved from works on paper to architectural projects on a large scale, which brought him closer to artists such as the artist duo Christo (1935–2020) and Jeanne-Claude (1935–2009). Konstantinov scaled his grids to monumental proportions.

The conceptual gesture of reproducing technical papers is to create two-dimensional spaces with their own mesmerising beauty. These works can be called dry, but they cannot be called immobile. In Konstantinov's ‘schemes’ there are shifts, constant impermanence, some equilibrium with a small error, that is, while seemingly identical, there are small changes in them, a vibration of form, on the verge of the noticeable, which creates a certain subconsciously felt tension in the viewer and makes them look closely at the (seemingly) repetitive works in search of differences, which are always there.

Konstantinov did not reproduce reality in the forms of reality itself. Although there is a kind of realism, it is the realism of a mathematician who sees the world through structures. And he reproduces that reality, which is always in his mind, graphically. Konstantinov's world is a space of animated formulas and models.

Konstantinov is one of the few Moscow conceptualists who is in no way connected with ‘Moscow romantic conceptualism’. His path to the idea did not come from late surrealism of Magritte, rather from minimalism. The classic ‘Kabakov’ version is not so much discursive as textual, not so much formal as figurative, not so much intellectual as social. Alexander Konstantinov did not work with text; his discursivity is the discursivity of mathematical analysis and spatial logic, not of Russian literature. His art does not require explanatory models that refer to the Soviet toilet or life in a communal flat. In the nineties and noughties, he gained international recognition with relative ease in Austria, Germany, Switzerland and the USA.

Konstantinov's solitary path was never easy. In terms of age, he did not belong to the dominant generation of non-conformists. Nor was he a member of any formal or informal Moscow art groups, nor did he enjoy the sympathy of their groupies. Throughout his entire life as a practicing artist, he was exhibited by only three Russian commercial galleries: once by the Moscow Collection, a couple of times by Segodnya Gallery in the 1990s, and three times by the Krokin Gallery, in the 2000s and 2010s. His work has never had a steady market in Russia.

Konstantinov became a museum artist even before the collapse of the Soviet Union. One of the first exhibitions of the first Centre for Contemporary Art on Yakimanka in 1990 was of Alexander Konstantinov together with Alexander Ponomarev. And the Tretyakov Gallery first presented his solo exhibition before he turned forty, in 1992, when solo shows by contemporary artists were still extremely rare in this museum. The market's neglect of him has been more than compensated for by the attention of Russia's leading art institutions.

“There are no collectors of my art in Russia,” Alexander Konstantinov used to say bitterly, as Yevgeny Ass, a friend of the deceased and architect of his exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery, recalls. Few of Konstantinov’s architectonic projects have been realised in Russia: one of them was the temporary facade of the Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val in 2006, another was the external superstructure of the walls of the dacha of gallerist Maxim Bokser. The largest of his architectural solutions was the ECCO power plant building in Luxembourg (together with BENG Architectes Associes, 2016). For GES-2, architect Ekaterina Vlasenko has recreated Konstantinov's works ‘The House Under the Lime Tree’ (2008, Hohenems, Austria) and ‘Blue Trees’ (2011, New York State, USA). Although designed for open spaces, they fit perfectly into the industrial building of the former Moscow power station, reconstructed by Renzo Piano, because GES-2’s central nave is a transparent-roofed city street, a new type of cultural ‘passage’. The house stands in the centre of this nave. And after the exhibition is over, both works will likely be moved to the new branch of the Tretyakov Gallery in Samara.

The exhibition opening at the Tretyakov Gallery brought together people who are not often seen together at any event nowadays, leading Russian curators and cultural strategists of the 1990s and 2000s, many of whom fell victim to the latest cultural policies: Leonid Bazhanov (who founded the National Centre for Contemporary Art, which was adopted by the state, losing its independence), Viktor Misiano (one of the initiators of the Moscow Biennale which no longer exists and the nomadic Manifesta Biennale), Andrei Erofeev (formerly organiser of the department of the newest trends and founder of the contemporary art collection of the Tretyakov Gallery), Zelfira Tregulova (former director of the Tretyakov Gallery), and Marina Loshak (former director of the Pushkin Museum) among others. All of them came to pay tribute to the memory of an artist with a paradoxical fate – in the limelight and under the radar at the same time.

Alexander Konstantinov. From Line to Architecture

Moscow, Russia

6 February – 26 May, 2024

Alexander Konstantinov. House of Air and Lines

Moscow, Russia

8 February – 26 May, 2024