Levan Chogoshvili and Georgian Modernism

A solo exhibition of this classic Georgian painter has opened at Atinati’s Cultural Center in Tbilisi. Russian critic Artem Dezhurko who has recently moved to Georgia, tries to decipher the complex network of cultural references, as elegant and cryptic as Georgian alphabet itself.

In the centre of Tbilisi, behind the Parliament, is the Atinati Cultural Center, where Levan Chogoshvili's (b. 1953) exhibition ‘Interling’ is currently on view. The tinted glass windows obscure the bright southern sunlight coming in from the street and the paintings are dark, some simply nailed to the wall. Atinati is a non-profit organisation to promote Georgian classical and contemporary art, they are active on social media, posting articles about medieval temples and frescos in English for an international readership. Levan Chogoshvili himself promotes Georgian cultural heritage in his contemporary paintings, so he seems the perfect ambassador for Atinati’s own institutional ethos.

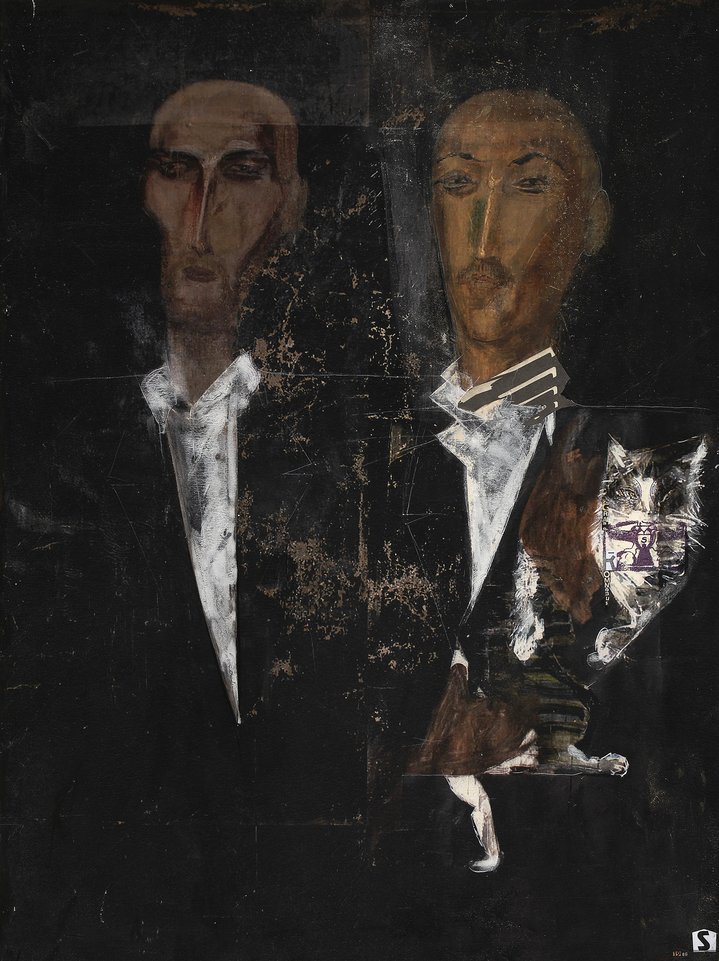

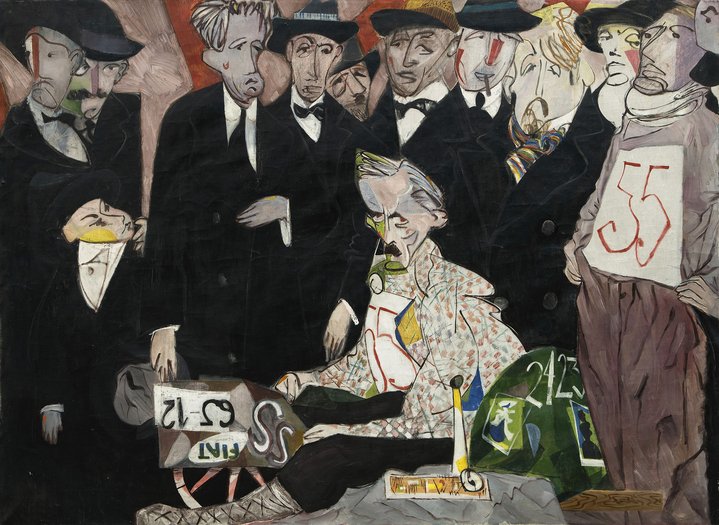

Levan Choghoshvili belongs to the generation of the 1970s, studying at the Academy of Arts in Tbilisi from 1970 to 1976. Chogoshvili's early paintings mainly belong to two series: ‘Venus and Mar(k)s’ (an erotic buffoonery with characters from the Soviet heroic pantheon) and ‘Destroyed Aristocracy’, based on group photographs of Georgian noble families in the early 20th century, many of which the artist sourced from his own family album. These works were never included in official exhibitions and until the mid-1980s, Chogoshvili was a semi-underground artist, taking part in apartment exhibitions, but at the same time he was well known and respected among Tbilisi intellectuals. In 1985 he painted a series of portraits of Kakhetian kings for the castle in Gremi, the old capital of Kakhetia.

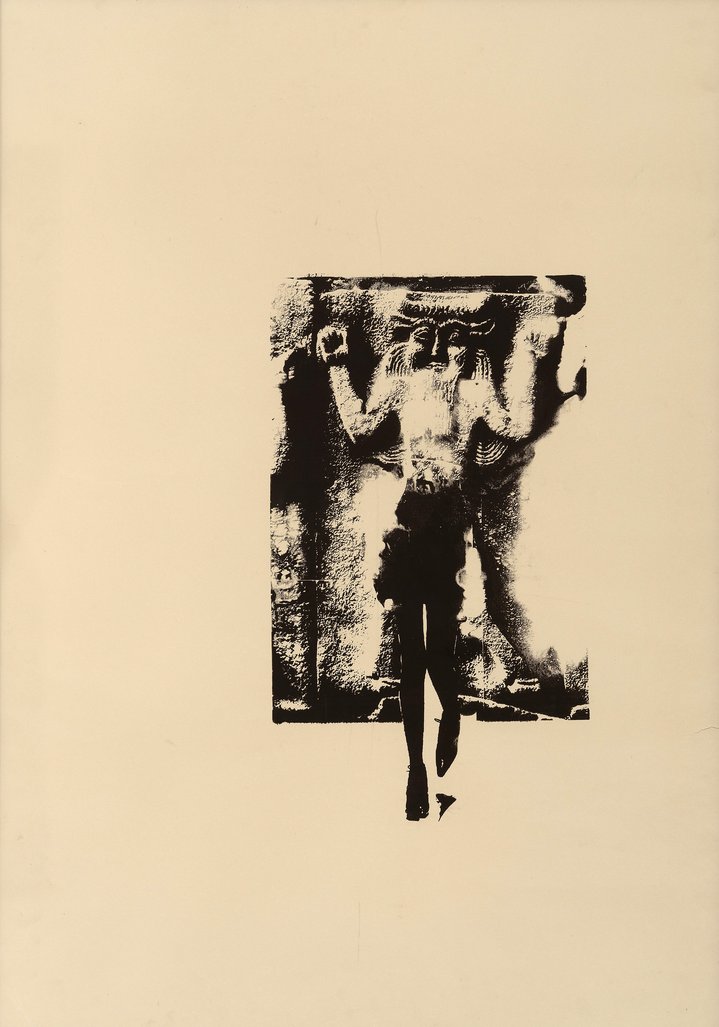

In the 1990s, Levan Chogoshvili often worked with his brother Archil and they staged performances and made videos together. Since the beginning of the 1990s, he has frequently exhibited outside Georgia, in France, Switzerland and occasionally in Moscow. Chogoshvili published the Iliazd - as the most important artist of the Georgian avant-garde of the early 20s, Ilya Zdanevich (1894–1975) called himself - and organized several exhibitions abroad devoted to the Zdanevich brothers, their legendary ‘Fantastic Cabaret’ and publishing house ‘41°’. The neologism interling, which became the name of the current exhibition is a distortion of ‘interlink’ with a hint of linguistics and was coined by the Chogoshvili brothers back in the 1990s, imitating the Iliazd’s wordplay.

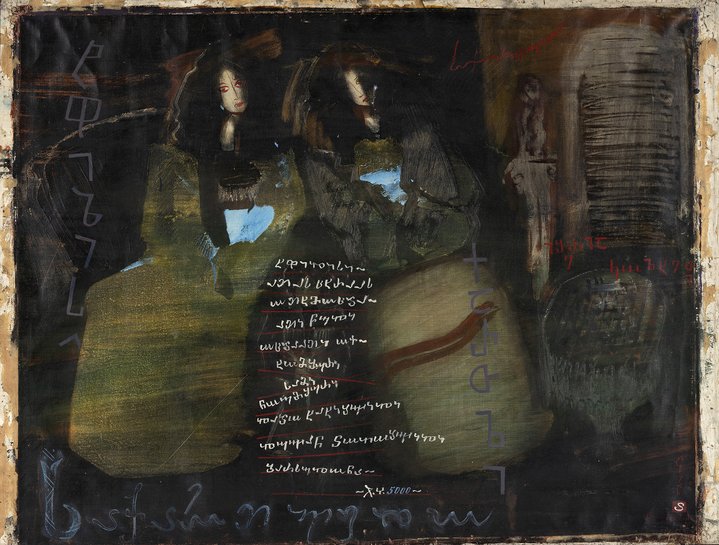

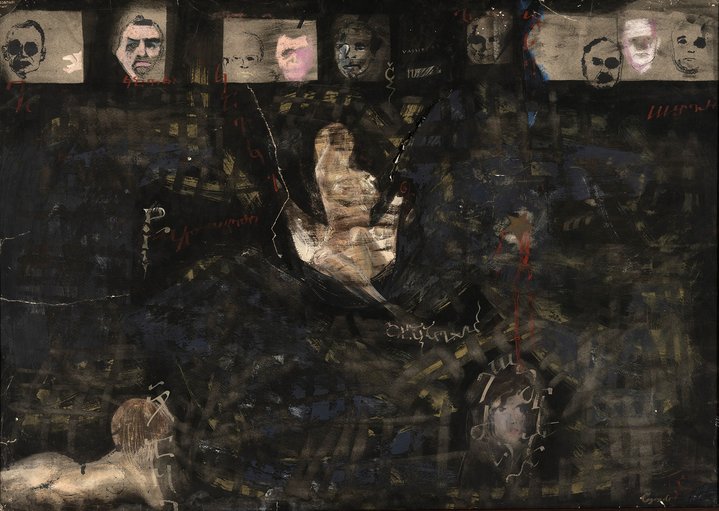

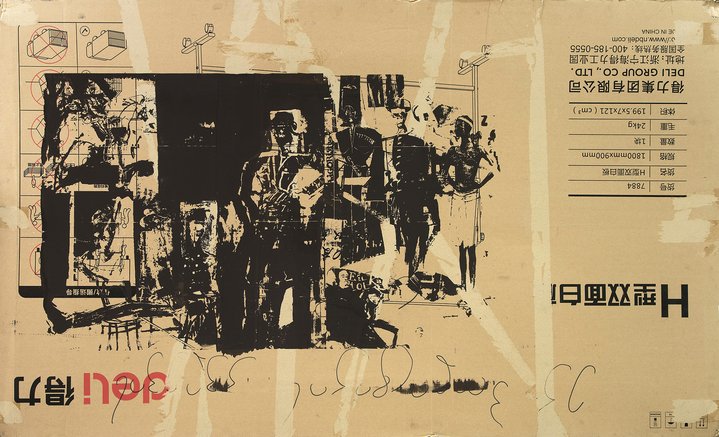

The exhibition at Atinati features 40 paintings and drawings from various years, from the early 1970s to the late 2010s, and there are five video works. Instead of the artist biography you usually find published on the exhibition walls, there is simply a table with a pile of documents and pages from old magazines displayed in glass cabinets. The texts are often incomplete with the pages overlapping each other. Levan Chogoshvili often uses a similar technique in his art using sandwich-like collages to compose his canvases. The most notable work in the exhibition, which is also featured on the poster, is a large panel made for the 2018 Kunsthalle in Zurich for the exhibition ‘Georgian Modernism: The Fantastic Tavern’. The exhibition was a historical survey about the work of Iliazd and the artists of his circle, and Chogoshvili's panel summarises its content. There are no images on it, only letters put together into words or scraps of words, sometimes they are written clearly, sometimes they are barely legible, and scattered around the surface randomly, in the spirit of the visual poetry of the Futurists and Dadaists. He also loosely reproduces fragments of Zdanevich's posters and typographic compositions.

The multilayered, patchwork structure of Chogoshvili’s work is similar to the way memory is constructed: it is fragmentary, the images flow into one another, and visual memories are mixed with snippets of overheard phrases. The faces in Chogoshvili's portraits are distorted, as if half-forgotten or seen in a dream. Through his deep interest in the Soviet 1970s as well as the era before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the artist reconstructs not the past itself, but how he remembers it.

Chogoshvili used to restore medieval frescoes and it is probably thanks to this that he learnt the ancient art of Georgian calligraphy and combined text and image in a single plane. Letters are drawn even more clearly and in more detail than the faces in his paintings. And when he is drawing he works with a pencil more like a calligrapher: he uses lines instead of building up form or shading in. His interest in graphic text brings Choghoshvili closer to his ‘protégé’ Iliazd, who was the first to leave his mark in history as a typographer.

Levan Chogoshvili's works seem difficult for the international art loving public to fully understand, because they were always intended for a Georgian audience immersed in its own culture. But, on another level maybe he had no interest in painting for others, his work more a calm, coherent, rational study of the self, where the process is more important than the result.