Exploring Immortality: Anton Vidokle’s ‘Citizens of the Cosmos’

Anton Vidokle. Immortality For All: A Film Trilogy on Russian Cosmism, 2014–2017. Exhibition view: Space Oddity, UCCA Dune, Beidaihe (7 March–20 June 2021). Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art

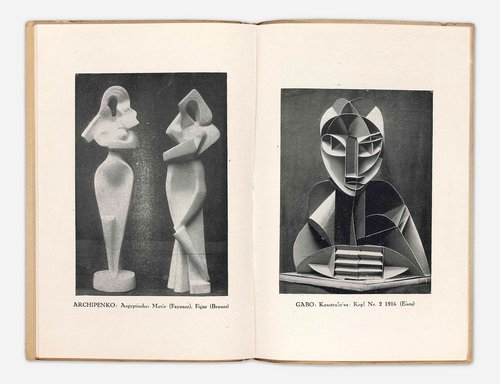

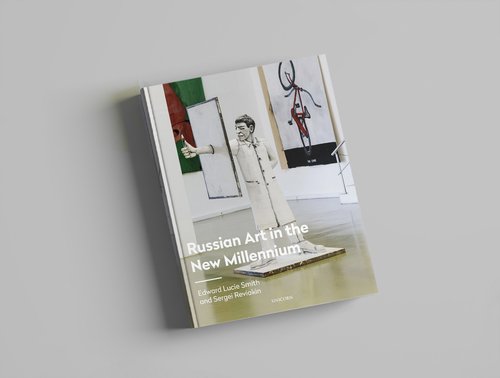

‘Citizens of the Cosmos’ by artist and e-flux founder Anton Vidokle was inspired by the cosmic vision of a Russian 19th century philosopher called Nikolai Fedorov (1829–1903). The book documents six films Vidokle made between 2014 and 2022, and features interviews, theoretical essays and film scripts.

‘Citizens of the Cosmos’ is a textual account of a six-film project compiled by Moscow-born, New York-based artist Anton Vidokle (b. 1965), which he has dedicated to Russian cosmic philosophy and the visionary philosopher Nikolai Fedorov. The book documents Vidikle’s own work and research which he undertook between 2014 and 2022 travelling around the world from the USA to Japan, Lebanon and Turkey to Russia, Ukraine to Kazakhstan. In an animated and engaging style, Vidokle takes us on a journey through cosmism addressing readers both knowledgeable and new to the subject.

The book starts and finishes with the transcripts of interviews. Vidokle’s first inteview is with British artist Liam Gillick (b. 1964) on the subject of ‘cinematographism’ and the vicissitudes of editing and sound design. The last interview with Indian art group Raqs Media Collective, resembles a performance script in which all members of the group participate. Packed between these interviews there are theoretical articles by art critics Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, Keti Chukhrov, Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Boris Groys and Daniel Muzyczuk, the curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lodz, Poland. They focus on selected aspects of Russian cosmism and how it relates to religious teachings, scientific knowledge, and the history of art, mostly that of the avant-garde.

The scripts of the six films in ‘Citizens of the Cosmos’ are published together in a separate block, interspersed with stills from each film which serves to give readers a good sense of the Vidokle project, even if they have not seen the films (there were several screenings at the 5th Urals Industrial Biennale in Ekaterinburg in 2019). The book is a good example of how art in new media and technology can be documented but there are shortcomings. There is no theoretical introduction or outline of the main ideas of the cosmist philosophers and the theoretical essays do not give a full picture of the movement.

Vidokle’s multi-part project was conceived long before the publication of his book when the world was very different and reading it today creates an inner tension. There are countries where the films were made which are at present in a state of aggression and Fedorov’s philosophy of cosmism and its ideas of universal brotherhood, immortality, and resurrection, do not sit comfortably with the current political situation of protectionism and isolation. Berardi presciently saw this contradiction in his essay, he writes: “Vidokle's return to Cosmism now is ... clearly situated at a moment when humanity is approaching the horizon of extinction. Confronting extinction from the point of view of immortality is a way to reactivate all the energies of imagination, of creation, and of struggle in contrast to the direction of the contemporary context of death.”

As interpreted by Vidokle and his co-authors, the seemingly idealistic utopianism of the cosmist view owes much to a contemporary scenario permeated by the threat of World War III and the fear of nuclear apocalypse. According to Berardi, the project can be viewed as “an exercise to continue along with the dynamics and phenomena of the catastrophe of our century, while aiming to revive the enchantment of modern revolutions, if along different principles of materiality.”

Finally, in his essay, Russian art historian and writer Boris Groys cements the artistic underpinnings of the philosophy of cosmism, noting that in Fedorov’s new order of things, “humanity must liberate itself from the power of nature that manifests itself in gravity, sexuality, and death.” Fedorov, Groys writes, wanted to turn the earth into a museum of humanity. “His way of overcoming the boundary between life and death does not bring art into life but transforms life into art. Human history becomes art history, because every human being becomes a work of art.”

The theoretical articles attempt to bring the idealistic, metaphysical ideas of today’s cosmists back down to earth, ideas which appear to be removed from contemporary reality. The book implies that Fedorov’s ideas and those of others like the scientist and mathematician Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935) should not be considered as a mirror of today’s world, but rather as an unquestionable reality in an antagonistic future on our planet.

Yet, a careful reading of the scripts of the six films reveal they are built on paradoxes. “The existence of the museum shows that there are no finished matters. For the museum, death itself is not the end but only the beginning,” a voiceover comments in a video sequence in which visitors in a museum are looking at skeletal remains of birds and taxidermy. “Death is responsible for the deepening roots of social injustice,” another voiceover says as a woman in a white lab coat presses her stethoscope to the trunks of bamboo trees and listens intently.

These are among the many actions, statements and interpretations which together form links in a chain of the ‘philosophy of the common cause’ that stretches from the posthumous publication of Nikolai Fedorov's similarly titled collection of essays in the 19th century to this contemporary publication of Vidokle’s ‘Citizens of the Cosmos’.