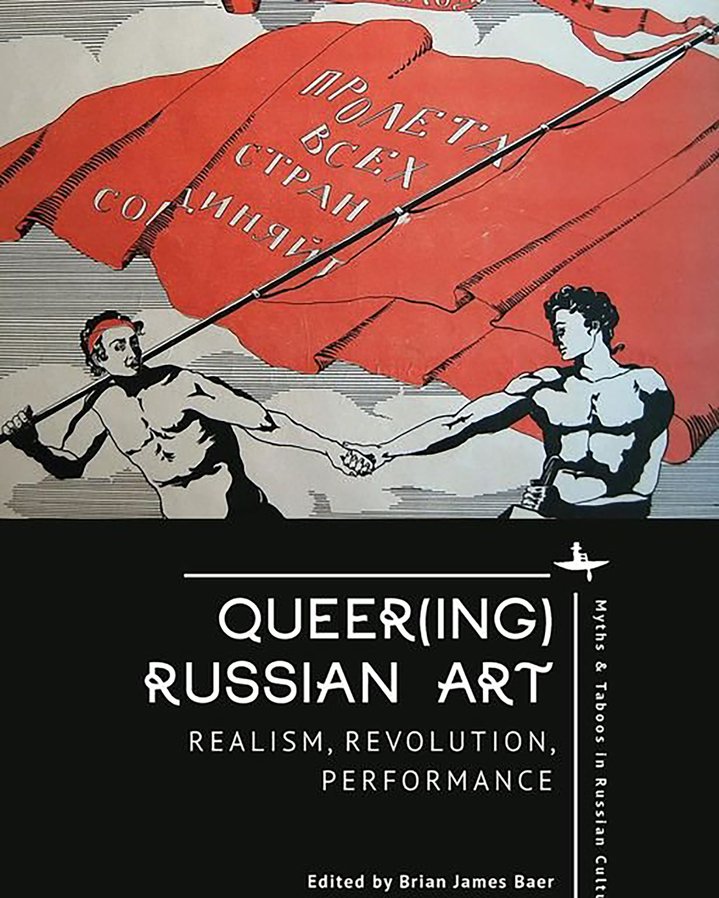

A New Book on Queer Art in Russia

Grigorii Mikhailov. Second Antique Gallery in the Academy of Arts, 1836. The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. Courtesy of Academic Studies Press and The State Russian Museum

A collection of essays called ´Queer(ing) Russian Art. Realism, Revolution, Performance´, recently published in the USA, is a much-needed compendium of LGBTQ+ themes and issues in Russian art both past and present.

One aspect of Russian visual culture which has been little explored and remains in the shadows, is that of queer art and queer themes. The recent publication of a collection of essays on the subject, compiled by Brian James Baer, Professor of Russian at Kent State University, and artist Yevgeniy Fiks (b. 1972), feels profoundly symbolic. Gender dissidence, to use historian Dan Healey's term, has traditionally been perceived in Russian art history as an awkward topic. It is considered too personal and therefore somewhat unimportant. This book is exceptionally timely: there is a new round of repression against queer people in Russia, which began with the ban on so-called ´homosexual propaganda´ first among minors, passed in 2013, then for everyone, from 2022, and this culminated with the recent ban on the activities of the international LGBT movement, which last month was officially recognised as extremist organisation in Russia

Although this collection of essays was in fact prepared for print some time ago, before the new legislation in Russia came into force, it still forms an indispensable general context. There are articles written by academics from across the world, and also interviews with artists such as Yaroslav (Slava) Mogutin (b. 1974), Maria (Masha) Godovannaya (b. 1976) and Yevgeniy Fiks himself. Some of the texts in the collection were written by the artists as their own independent projects or are scripts for them.

´Queer(ing) Russian Art´ draws on the definition of queer proposed by the Australian theorist Annamarie Jagose as ´the post-structuralist figure of identity as a constellation of multiple and unstable positions´. Queer is understood as a figure of questioning and resistance to the existing status quo based on gender socialisation and related ways of perception. The history of queer art in Russia may not have been written yet, but conversations about Russian queer art, as the book emphasises, should not be simply limited to the outing of artists and other protagonists in the nation's art scene. The aim of the book is to show how "the production, circulation, and reception of queer art [is possible] above and beyond the sexual orientation of the artist, although not excluding it". In addition, it aims to overcome what it identifies as the reluctance of art historians, curators and art dealers to see queer art as anything other than a highly subjective issue.

In addition to the notions of queer and queer art, the collection thematises notions of Russian art as a multicultural space united by a single imperial label. In addition to artists who live or have lived in Russia, the book includes other peripheral figures such as Babi Badalov (b. 1959), an artist of Azerbaijani origin who, although he worked for some time in Russia, now lives in France, and turned his uprootedness which underscores his artistic method into any context or language, and is consonant with the optics of the queer.

As in any such compilation, the articles do not form a coherent picture, but, taken together, they do form a chronological sequence from the art of the mid and late 19th century to Socialist Realism, the Soviet underground art, and then the art movements of post-soviet Russia, until the mid 2010s. With the exception of Brian James Baer's introductory article on queer beauty and Olga Khoroshilova's historical study of Images of Androgyny in Eighteenth-Century Russia, most of the texts focus on specific artists. Writer Nikolai Ivanov, in his analysis of Alexander Ivanov (1775–1848), discusses the artist's paintings of male nudes. Another article (also by Brian James Baer) is devoted to Konstantin Somov (1869–1939) and his frivolous Art Nouveau graphic vignettes, whose libertinage went way beyond what the era allowed but today remain heavily culturally mediated.

A detailed historical and biographical essay is devoted to the figure of Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948), whose homosexuality has been the subject of numerous researchers. Its author, Ada Ackerman, examines the director's own ideas about the nature of bisexuality as "a powerful dialectical unity of opposites and which he construed as a re-enactment of a primordial stage in one's evolution, before sexual differentiation". The subject of her interest, however, is not mere biography, but Eisenstein's drawings, many of which were openly homoerotic. Some of them were the result of his trips to countries with greater sexual freedoms, and on his return to the USSR they gave Eisenstein "an opportunity to revive scenes of sexual freedom" amidst the growing Stalinist terror.

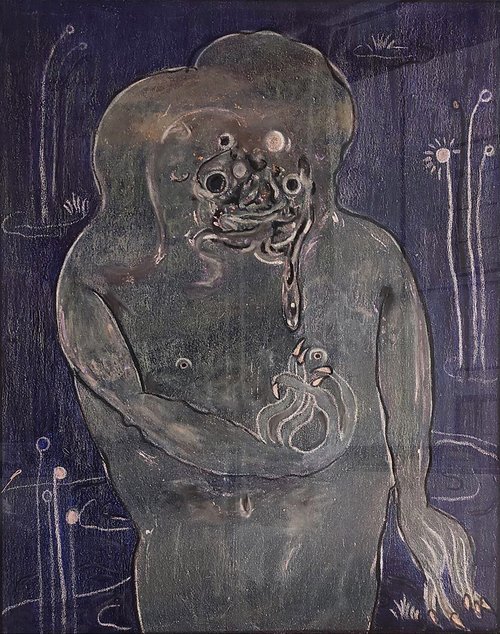

Almost one third of the book is devoted to Timur Novikov (1958-2002), the artists in his circle and the New Academy of Fine Arts which he founded. However, the hero of this chapter is not so much Novikov himself as three of his contemporaries: Georgy Guryanov (1961–2013), Bella Matveeva (b. 1962) and Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe (1969–2013). Within the utopia of "eternal and perfect beauty" proclaimed by Novikov, these authors appropriated and reinterpreted the aesthetics of Socialist Realism and Soviet culture per se, re-sexualising the Soviet body and the masculinity of the Soviet era.

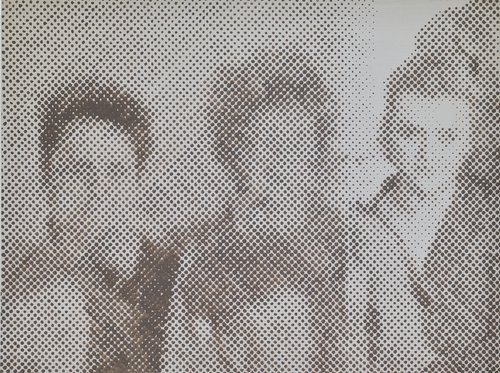

Bella Matveeva, as Helena Goscilo writes, de-heterosexualised her models in part through the arrangement of human bodies in couples. In her works there are not only male homosexuals, but, in the spirit of the times, also lesbians, the genealogy of which Goscilo traces back to Russian symbolism, but also to the broader context of popular culture, for example, the songs of the Russian pop band t.A.t.u. In an article comparing Guryanov and Monroe, Andrey Shental writes, on the one hand, about the latent homoeroticism of Soviet painting and cinema, scenes from which Guryanov appropriates and reinterprets. And, on the other hand, about the "encyclopaedia of gender norms" and the "normalised and commercialised codes of western drag culture" that Monroe confronts in his work.

The critique of gender normativity, according to Maria Engström, in Guryanov's case also manifested itself at the level of his lifestyle. His inherent dandyism and that of the artists in his circle served as an antithesis to the intellectual nonconformism of the Moscow scene, in which, to use a quote from Susan Sontag, interpretation prevailed over eroticism.

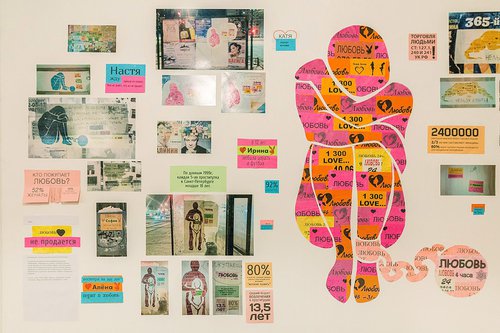

In the works of these artists the theme of sexuality was not completely silenced but was the subject of reticence and numerous metaphors. However, in the 2010s, as Seroe Fioletovoe emphasise, queer sexuality and its symbols came to the fore, not as a subject of independent reflection and an area of subjective practices, but rather as "a tool for opposing different power structures [and] political religious power discourse".

Fioletovoe´s article (who identifies as ´they´) is called ´The Battle over Names´, a title that emphasises the need to fight for the preservation even of one's own name/s and personal symbols in the predicament of forceful repression of everything that concerns the optics of Queer. In the context in which the book has been published today, this seems particularly relevant.

Queer(ing) Russian Art. Realism, Revolution, Performance. Edited by Brian James Baer, Yevgeniy Fiks

Boston, USA