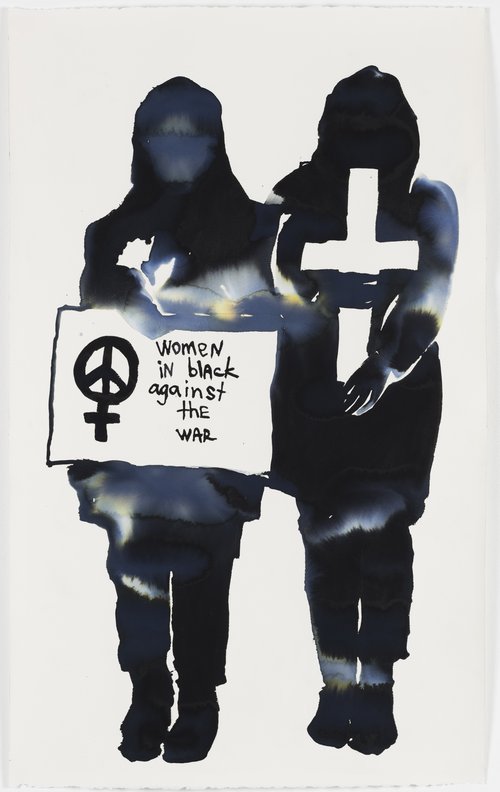

Ekaterina Muromtseva. Sleeting pellets, 2024. Northern Alps Triennale. Nagano Prefecture, 2024. Photo by Hirabayashi Takeshi. Courtesy of the artist

Ekaterina Muromtseva, a Russian Whistler in Japan’s Northern Alps

Russian artist and philosopher Ekaterina Muromtseva explores the intersection of Japanese storytelling and Western philosophical parables in her project for the Northern Alps Triennale in Japan. Through the use of narrative, shadow theater, and abstract watercolours, her work engages local communities, blending cultural elements with a deep sense of place.

While the press waits for their bento lunch boxes, the storyteller recites a local tale about a dragon and a water spirit. She reminds me of the Sirin bird, portrayed by Lidiya Vertinskaya (1923–2013) in the Soviet movie Sadko (1952). Each word is in its place, stitched together with the precision of her laced dress. For the Northern Alps Triennale in Nagano Prefecture, Ekaterina Muromtseva (b. 1990), a philosopher and artist of Russian origin, found one such storyteller in the city of Omachi. Reiko was flattered and gladly accepted the invitation to read three philosophical fables written by Muromtseva: ‘Sora’s Second Tail’, about a cat who dreamt of having two tails, ‘Whistling Mountains’, about a benevolent cicada, and ‘Monkey Catcher’, about magical monkeys, doppelgängers, and mirrors.

Muromtseva found herself inspired by her personal encounters with locals in Japan, and she transformed them into the magical animal protagonists of her fables, bringing to mind Vladimir Propp (1895–1970), a Russian theorist of the fairy tale. The details in her stories are drawn from the reality of Omachi City: small trains, singing cicadas, aggressive monkeys, and clever cats. However, the magical world she creates bears little resemblance to the mystical cosmos of Japanese folklore. Instead, it follows the taste and logic of Western philosophical parables. This synthesis might raise questions about how appropriate this practice is and whether the use of Japanese motifs in a European work of art strays into Orientalism, something which the project as a whole rebuffs. However, the rest of the project offers a resolution to this pressing issue.

“It is important for me that the hosts of these places are not only performers but also subjects of creativity, together with me” Muromtseva told me. She decided to divide the project into three parts. The first part is a narrative: on the stage of a Noh theater at Sasayaki a semi-abandoned Shinto shrine, there are three video installations called ‘Whistling Mountains’. In them, a storyteller retells Muromtseva’s tales in Japanese, while black silhouettes are animated on a screen. Local pianist Spannkosmo composed a musical score for Muromtseva, beautiful and reminiscent of the late Ryuichi Sakamoto (1952–2023).

The second part, a shadow theater ‘Three whispers’ is set in a calligraphy room in the same shrine. Spectators sit in a dim light on the tatami floor and create their own stories and tales. Surrounded by the twilight of a cedar forest, figures dance on walls made of thin rice paper, and along with them, ancient myths about shadows, caves, and their inhabitants emerge from the depths of the subconscious. It brings to mind Christian Boltanski (1944–2021), whose shadow works are featured in several parts of the same Japanese triennale ecosystem: in Setouchi and Echigo-Tsumari.

For the third part of the project, we descend from the mountains to the valley, where an akiya one of many abandoned traditional-style houses with a quirky structure is located in the city centre because a canal with clear water runs through the foundations of the building. The loud chirping of a mountain stream resonates with the rustling of precious French watercolour paper, stretched from floor to ceiling in a spacious room above the stream of water. On huge vertical sheets, Muromtseva has planted watercolour seedlings, which have sprouted into abstract landscapes called ‘Sleeting pellets.’

Storytelling holds an important place in Japanese culture. For example, the history of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is kept alive not only through the voices of surviving witnesses but also by the next generation, the witnesses of the witnesses, referred to as denshosha. They do not simply retell what they have heard from primary sources; they memorize the stories word for word in the hope that no one will ever repeat the grave and tragic mistakes made by the American air force in August 1945. Oral history is incredibly resilient. It helps people survive the apocalypse and come to terms with the past, with all its traumas, bringing meaning and understanding.

The Northern Alps Art Festival is a new event, only in its third iteration. It is centred in the small city of Omachi, nestled in a picturesque valley surrounded by two lakes, buckwheat, and rice fields. During the economic peak, the city experienced a tourist boom, followed by decline and depression. When the festival began in 2017, remembering the apocalypse of the economic crisis, locals initially met the organizers with suspicion. Moreover, among all the Japanese triennales, this one stands out for the labour-intensive involvement of local volunteers in the creation of artworks and it has been much criticized for this. This year, for example, locals helped Canadian artists Caitlind R.C. Brown & Wayne Garrett gather and bring 14,000 optical lenses to their art installation.

At the end of last year when I met Muromtseva after her month-long residency in the cold Northern Alps of Japan she told me that one of the principles of her work in Japan is site-specificity. As with her previous project for the local triennale, which Art Focus Now wrote about in 2021, the artist chose to work with cultural material. The form of parable emerged during her battle with COVID, Muromtseva recalled: “I felt the life force draining out of me, and the only thing I could do was follow my imagination.”

It was curator Fram Kitagawa who first came up with the idea of the triennale in Japan, who saw it initially as a healing remedy for the depression affecting Japan's depopulating rural areas. This remedy was called revitalization, but following the medicinal metaphor, sometimes vitamins are not enough, and a struggling organism requires some kind of therapy. Caitlind R.C. Brown & Wayne Garrett, Nikolay Polissky (b. 1957) and other guest artists who relied heavily on local volunteers offered labour therapy. In this context, Muromtseva’s project can be seen as a form of art therapy, incorporating elements of philosophy, the theatre, music and subconscious play.

Northern Alps Art Festival

Omachi City, Nagano Prefecture, Japan

September 13 – November 4, 2024