Costakis: Art Above Politics, From Catholic Monastery to Tobacco Factory

Kazimir Malevich. Female Portrait, 1910 – 1911. Courtesy of The Russian Museum Collection, Malaga

Established in 2015, a branch of the Russian Museum housed in a 1920s tobacco factory in Malaga faced near closure in 2022 when EU sanctions forced the return to Russia of the artworks which were on display. Since then, successive exhibitions of private collections of Russian art formed by international collectors have kept the flame alive, and now 450 works belonging to the legendary George Costakis are on view.

During the perestroika era people often spoke of art being above politics, of how art is a cultural bridge between nations, but the 1990s was a decade of rapprochement and these were easy words to use, they went with the grain. These days I have not heard cultural influencers speak about using art to bring people together, it seems this communication channel has broken down. As both individuals and institutions in the West, we shy away now from Russian artistic projects because we are afraid that this outspokenly aligns us with a certain political stance or values at a time of armed conflict and painful divisions.

So, on the face of it, to mount a huge exhibition of Russian art in Western Europe during the worst conflict since World War II might be seen as an audacious step. This exhibition, ‘Utopia and Avant-garde’ of Russian art from the Costakis collection at MOMus in Thessaloniki, acquired from the family by the museum in 2000, brings over four hundred works by Russian artists to the westernmost shores of Europe. The exhibition is the result of a collaboration between two European city museums, the type of institutional collaboration which has become even more common in the wake of the world financial crisis as museums everywhere are cash strapped yet have audiences with ever demanding interests as well as the need to reflect changing values. There is no obvious geopolitical agenda lurking behind the show.

The Russian Museum branch in Malaga is part of a group of art institutions in the city which includes the Casa Natal de Picasso. As part of a cultural exchange, an archive featuring drawings, prints, ceramics and letters between Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and his friend the barber Eugenio Arias owned by the Casa Natal since 2017, is being lent to MOMus in Thessaloniki, while over a third of the entire Costakis Collection in its holdings is being lent out to the Russian Museum in Malaga until Spring next year, if not longer. It is impossible to imagine this collection being exhibited at present in one of Western Europe’s major capital cities, like London, Paris or Madrid.

Although Malaga’s cultural status has grown over the past decade, now with the Pompidou Buren ‘Cube’ on the waterfront, and the city attracts vast numbers of visitors, its art infrastructure is still evolving, and the opening of the exhibition did not attract the international art community; it was entirely a local affair. I took the train from Madrid to Malaga for the private view on the first night where I found the spacious, yet dark rooms packed with an enthusiastic, apparently open-minded local crowd of cultured Malagueños of all ages, who seemed less interested in small talk and more focussed on the extraordinary art on the walls, peering, pointing, gesticulating with what appeared to be genuine curiosity. There is nothing ordinary about the Costakis collection, each work is a masterpiece in its own way, from small canape sized pencil sketches by Ivan Kliun (1873–1943) to the prescient and stark ‘Suprematist Cross’ by Ilya Chashnik (1902–1929) a white cross on black ground, the cross dividing the picture surface into nine back and white squares, one of the standouts on view. And not to mention the exceptional works by Liubov Popova (1889-1924) one of Costakis’ favourite artists.

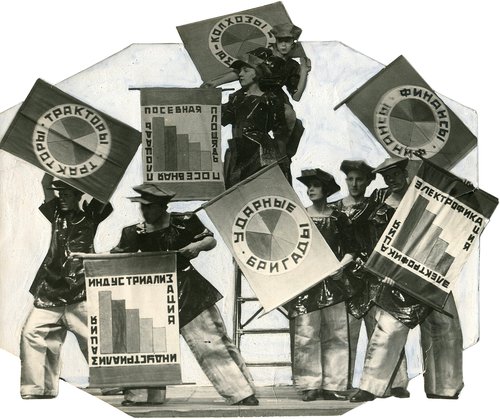

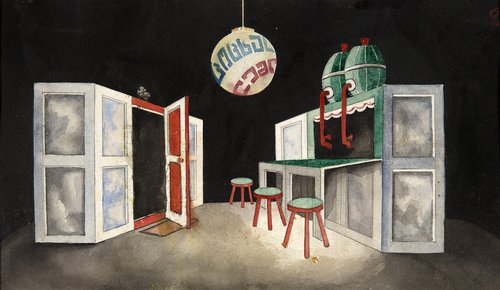

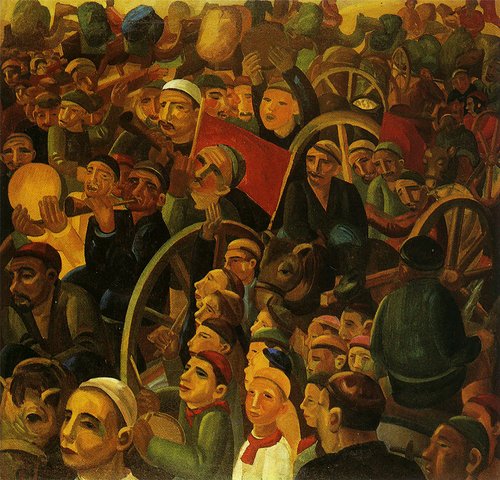

It strikes me as ironic that despite the pioneering, revolutionary works themselves, this is a show curated to be unapologetically conventional. Starting in the first room, it takes your hand and walks you through the Russian avant-garde, from its roots in French Post-impressionism and European Symbolism, to Russian Cubo-futurism, and eventually to Suprematism and Constructivism, peppered with other parallel trends, like the Analytical school and Cosmism, the last room a small showing of figurative works by lesser known artists, the coda is in some ways invisible after the feast.

‘Utopia and Avant-garde’ aligns itself with one of the main goals of MOMus: to use the Costakis collection to educate the public about the Russian avant-garde. Parts of the collection travelled extensively throughout Europe from as early as the late 1970s, and since 2000 (once acquired by MOMus) there have been a considerable number of projects co-curated together with Western European and Russian state museums ensuring the collection is being seen by a wide audience. Just within Spain, there was ‘Building the Revolution’ at LaCaixa in Madrid and Barcelona (also London’s RA and in Berlin); and ‘Rodchenko-Popova: Defining Constructivism’ at the Reina Sofia in Madrid which also showed at Tate Modern in 2009. A year later there was the ‘Cosmos of the Russian Avant-garde: Art and Space Explorations in Russia’ at the Botin Foundation in Santander (2010–2011). It is a generous, open, expansive and liberal approach to sharing a collection which otherwise is permanently housed in the old Lazariston Monastery in Thessaloniki.

Some will be disappointed that there is no attempt made to reclassify artist nationalities, or present the Russian avant-garde as a more fluid, transnational, inclusive movement, controversial at a time where people across this geography are searching for a deeper sense of their national identities, both in Ukraine and Russia. Costakis himself criticised Camilla Gray’s famous book ‘The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863 to 1922’ stating in an interview in the New York Times in 1975 “It is not correct to call it ‘the experiment in Russian art … it would be more appropriate to call a book about this movement ‘The pioneers of Avant-garde in the 20th Century’. Yet the story of the Costakis collection itself is intimately connected with the Moscow art world of the 60s and 70s. His three-apartment co-joined white walled Vernadsky Prospect home hosted not just Western luminaries the likes of Ted Kennedy or the writer Bruce Chatwin but more importantly Russia’s underground artists for whom encounters with the art on the walls were invaluable, creating a movement which became known as the ‘second avant-garde’. More than this, Costakis wove a thread through the 20th century, the finished tapestry far more important than a personal legacy. Who has not wanted to enter the hallowed rooms of his apartment, hung floor to ceiling, and not felt for an instant a longing to have been there, and to become part of the bigger narrative Costakis represents of salvation in the face of destruction by a dictatorial state. Who cannot either sympathise or identify with this? Showing a core group of works from this collection, to tell the simple story of how this complex art came about, and what made it special and different, this message is timeless.

In Malaga the tourists will vote with their feet. Those that do make it over to the Tabacalera will have a treat in store because this show is a blockbuster exhibition, possibly the best ticket in town this summer, worthy of being staged in any capital city, a well-rehearsed story by an institution that has carefully nurtured the collection over quarter of a century on what is still an often-overlooked chapter in world visual culture. The Tabacalera itself is a fitting place for the collection, a reminder of George Costakis’ father Dionysius who was a tobacco merchant on the Greek island of Zakynthos, before he moved to Moscow where he joined a large tobacco firm which he later owned. And his grandfather on his mother’s side had been a tobacco merchant in Tashkent.

Utopia and Avant-Garde. Russian Art in the Costakis Collection - MOMus

Malaga, Spain

4 July, 2024 – 1 May, 2025