Chernikhov’s Imaginarium

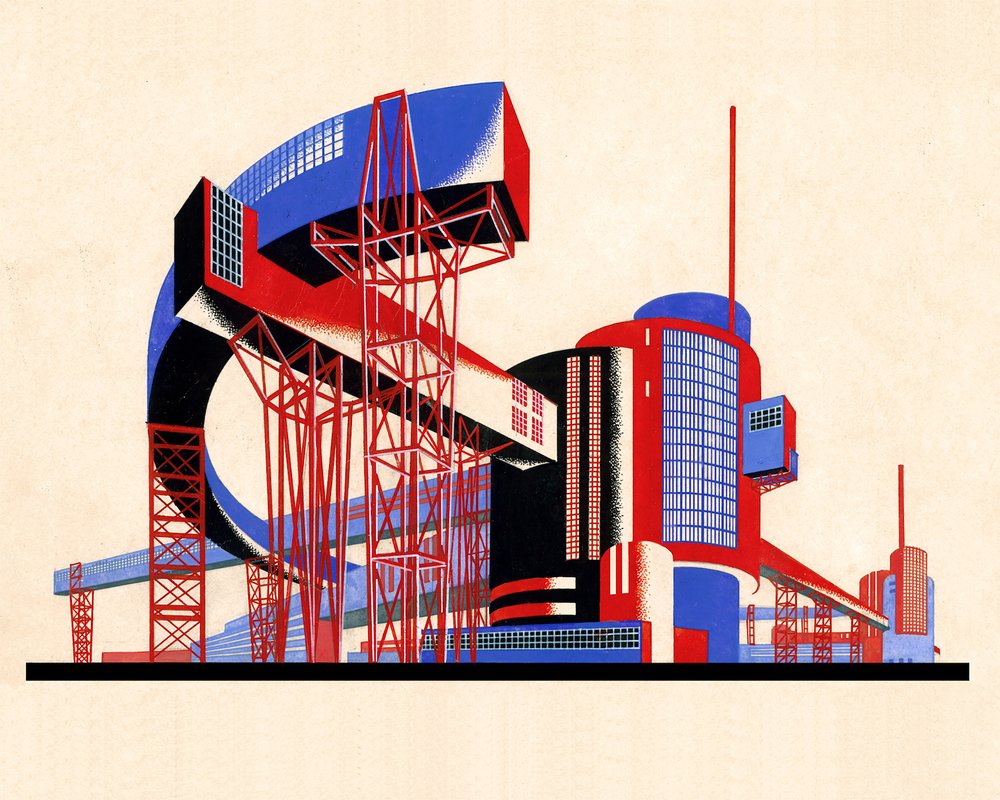

Yakov Chernikhov. Fantastical composition of the organization of space of complex in form and combination of elements of structure No. 28. From the ‘Architectural cycle’. Courtesy of Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre

Woven like a dream, an ambitious exhibition of the work of Yakov Chernikhov at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre in Moscow convinces viewers that the genius of this visionary avant-garde architect lies in his ability to remain a great mystifier, outwitting all the pseudo-scientific theorists of the creative process.

The art of Yakov Chernikhov (1889–1951) is embodied primarily in his works on paper and books, published in the late 1920s to early 1930s, with one posthumous book, ‘Construction of Typefaces,’ which came out in 1958. There is only one building he actually realised: the rope workshop with water tower at the Krasny Gvozdilshchik factory on Vasilyevsky Island, Saint Petersburg. This factory produced utilitarian metal goods such as bolts, wire, nails, and ropes and the exhibition includes a model of both the workshop and tower. Chernikhov's architecture is rather typical of good avant-garde industrial construction but his genius lies elsewhere: in the ability to weave the entire universe in a delicate graphic mesh.

Cascades of forms, figures, and lines flow through Chernikhov’s work like torrential rain. The curators of the exhibition, the grandson of the architect Andrey Chernikhov a professor at the International Academy of Architecture and Maria Gadas, head curator of the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, have brought together a collection of some five hundred items which they have divided into eight chapters. Under the excellent vision of architects Kirill Asse and Nadia Korbut, the collection is transformed into a dynamic, flowing stream of images which are projected onto the walls, immersing visitors in an atmosphere evoking video games and virtual labyrinths. It is an apt choice. The journey visitors make through the rooms of the exhibition includes space for frequent pauses and a material world which has been lovingly created. The interior of Chernikhov’s study in his house on the Griboedov Canal is brought to life, with quintessential St Petersburg domesticity marked by a green lampshade, a desk ornament, and views reminiscent of Mir Iskusstva (World of Art). Microscopes used by Chernikhov to observe how microbes from the Red Army Institute’s laboratory stretched into chains of abstract geometric shapes, in the spirit of Malevich, are also displayed. An excellent coda to the exhibition is an invitation to the discussion of how his World War II studies in military camouflage using “disruptive patterns” between object and background influenced the emergence of post-war abstraction.

One key concept in discussing Chernikhov’s life and work which the curators have aimed at putting across in this show can perhaps be best described as a “downpour of images.” Through his unrelenting creative will and reproduction of symbolic forms ad infinitum, Yakov Chernikhov was a prophet of semiotic algorithms, digital communication systems, and online psychedelia – from web design to virtual video game locations.

Through an encounter with Chernikhov’s images and as you read his quasi-scholarly notes you sense clearly that the bubbling life and physiology of symbolic form triumph over the pedantic classifier. To the point of obsession Chernikhov created catalogues, archives and tables. Yet it feels as if he systematised the chaos of uncontrolled growth of forms and shapes of life.

The strange schizoid splitting of Chernikhov’s world is partly explained by his biography. He was born in Pavlograd in the province of Ekaterinoslav, one of eleven children. As a youth and to earn a living, Yakov worked in a photographic studio as a retoucher, a loader, a joiner, and a wall painter – undoubtedly crafts which developed his phenomenal attention to detail and keen observational skills. Then in 1914, Chernikhov moved to Petrograd (now St Petersburg), first enrolling in the painting and then the architecture faculty in the Academy of Arts. For the avant-garde revolutionaries of the generation of Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) and El Lissitzky (1890–1941), this sounds as total nonsense. For the die-hard avant-gardists the Academy was a bastion of obscurantism, routine, and their fiercest enemy. Yet Chernikhov seemed to introduce the refined constructions of the Silver Age draughtsmen into his futuristic worlds. He was rightly called the Soviet Piranesi. Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) was a powerful 18th century avant-gardist. In his etchings, within the academic system, Piranesi tore architectural designs from their 3D bonds and launched them into a new orbit where form and function interact. For Piranesi, architecture became the ruler of the universe. It abolished subordination and became the lawgiver of spatial relations, enslaving people with their petty demands and limitations. Likewise, Chernikhov thought in a similar, total manner. He proposed a universal principle governing the birth and life of symbolic form, subordinating everything – from typeface design in books to factory buildings, houses, and planetariums. In Chernikhov Mir Iskusstva (World of Art – an artist association developing the principles of art nouveau style – Ed.) elegance and flexibility of lines inherited through the academic system combined with revolutionary ideas about constructing objectlessness and prioritising space over function. Chernikhov continued his education at the VkhUTEMAS-VkhUTEIN art school. In 1927 he founded his own studio in Leningrad, the Scientific-Research Experimental Laboratory of Architectural Forms and Graphic Methods, where he taught and worked on projects with students.

I quote from his first published book, ‘The Art of Drawing’ (Leningrad, 1927): “‘Object,’ as such, plays no role in all the presented material of the draughtsmanship course. The entire course is chiefly built on the principle of ‘objectlessness.’ Only sections dedicated to volumetric solutions give some notion of ‘certain’ objects. Nature is not applied in any case. The entire methodological basis of the draughtsmanship course, as considered in the present graphic material, rests on ‘combination,’ on the ‘union’ of line-plane and volume, outside of any object. Just as a corresponding combination of sounds gives us a piece of music, so we will build and compose such an image where lines are musically tuned. We will reveal the true beauty of the line and connect one curvature with another as notes are linked in music. We will apply this approach to plane and volumetric compositions alike.”

Chernikhov combines Malevich’s radical suprematism with the psychoanalytic spatial thinking espoused by the school of rationalist Nikolai Ladovsky (1881–1941). However, in his 1931 book ‘Construction of Architectural and Machine Forms’, Chernikhov emerges as a theorist of constructivism, opposed by the rationalists and Malevich. He rejects narrow pragmatic functional design and opposes “orthodox” VKhUTEMAS constructivism: “Constructivism for its own sake is a useless and meaningless stance. Constructivism should not serve ornamental ends, disguise the essence, or be a false cover of forms. Only constructive solutions that harbour essential functional, rational and purposeful intent make sense. Inventing construction for aesthetic representation is a sham. Exaggeration and highlighting construction is unnecessary flaunting and vulgarising it. Every constructive architectural structure, like every machine, must possess organic unity of all elements with functional and rational cohesion of individual constructions.”

It seems Chernikhov was synthesising all schools and methods – rationalism, suprematism, Mir Iskusstva-style pastiche, constructivism – to create a new, all-embracing universal textbook of form-making. Truly a Borges-like theme!

The exhibition at the Jewish Museum resembles a laboratory of eccentric scientists from sci-fi novels. It recalls Chernikhov’s abundant drawings and paintings of gigantic palaces of socialism in the 1930s and 40s, where rationalism and constructivism principles merge with the new Art Deco style, combined with the wise hierarchy of Gothic pointed arches and vaults. Such thickets and forested glades of geometric bionics grew in the laboratories of the visionary Yakov Chernikhov, becoming propylaea of the architecture of the modern era.

Yakov Chernikhov. Images of the Future. Architectural Fantasies of Russian Avant-Garde

Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre

Moscow, Russia

19 September 2025 – 11 January 2026