A St.Petersburg Show Sheds New Light on 20th Century Sculpture

Interlinking of Forms. Russian Sculpture. 20th century. Exhibition view. St. Petersburg, 2023. Courtesy of the Press Service of The Manege Central Exhibition Hall

The ambitious exhibition ‘Interlinking of Forms. Russian Sculpture. 20th Century’ at the Manege exhibition hall in St Petersburg invites visitors to look at the country’s history through the lens of sculpture and cinema.

It may be an epilogue to the Manege’s recent comprehensive survey of 18th and 19th century sculpture but this new show brings together over three hundred sculptures by hundreds of artists from some forty-eight museums scattered all over Russia and numerous private collections. The word ‘show’ is fitting as the artworks are combined with documentary cinema footage. “The 20th century was the first to ever be captured in motion”, curator Elizaveta Pavlycheva explained at the exhibition opening. The connection between these two distinctive media is most obvious in the genre of portraiture, as the curated selection of footage includes many close-ups of those Soviet leaders and cultural celebrities whose busts gaze at the viewers condescendingly from a huge three-story shelf-like construction at the entrance. “Sculpture has its own inner dynamics and we wanted to contextualize it through the medium of cinema”, added Innokenty Ivanov, the exhibition’s co-curator responsible for the cinematographic side of the project.

Cinematography lies at the heart of the show’s structure. Spread over two spacious floors of the Manege, are chapters with titles like ‘Screenplay Plan’ which sets out the main social and historical milestones of the 20th century that influenced the development of sculpture; ‘Cast of Characters’ which comprises busts of prominent figures of the 20th century; ‘Starring’ which present models of monuments including those which were never realized; ‘Montage and Colour Correction’ which explores colour and abstract sculpture; ‘0+’ for children's images in the sculpture of the 20th century and ‘18+’ for nude sculptures, (the latter two referring to the Russian system of age-limit ratings for films and other cultural production). The final part of the exhibition, ‘Wide-Format’ is dedicated to the theme of labour, which is mostly expressed in statuary groups or populous bas-reliefs.

Although the exhibition took two years to research there is the sense that Elizaveta Pavlycheva and her team of co-curators were unsure which pieces to show until the very last moment as on the opening night many artworks still lacked labels. Looking at the sheer scale of research undertaken, you might expect to see a vast array of masterpieces here, but the focus is not on timeless beauty rather the bizarre, the unknown and the unexpected. It is one of the exhibition’s strengths that it has avoided the stiffening embrace of the Socialist Realist canon that dominated Soviet sculpture for the best part of the century. Where the choice of artworks at times raises eyebrows this valiant effort to look beyond the propaganda grandeur of Soviet classics is worthy of recognition.

The coloured sculpture section includes amusing examples of naive art such as brightly painted wooden bas-reliefs by Alexey Pichugin (1909-1999) which re-create 19th century grand neo-classical Russian paintings such as ‘The Last Day of Pompei’ by Karl Briullov (1799-1852) and ‘The Appearance of Christ before the People’ by Alexander Ivanov (1805-1858). Tiny, rarely shown sculptural caricatures of celebrities were unearthed from remote corners of museum vaults. Oddly and unexpectedly, subdued wry humour pervades the whole exhibition, affecting even the layout of the chapters. Models of monuments are placed opposite the Nudes so ‘Lenin’ by Veniamin Pinchuk (1908–1987) stares intensely on Nikolay Silis’ (1928-2018) wooden driades ‘Morning, Day, and Evening’. A step away Yuri Orekhov’s (1927-2001) brooding dissident Andrei Sakharov stares disapprovingly at Lev Kardashev’s (1905-1964) sultry nude.

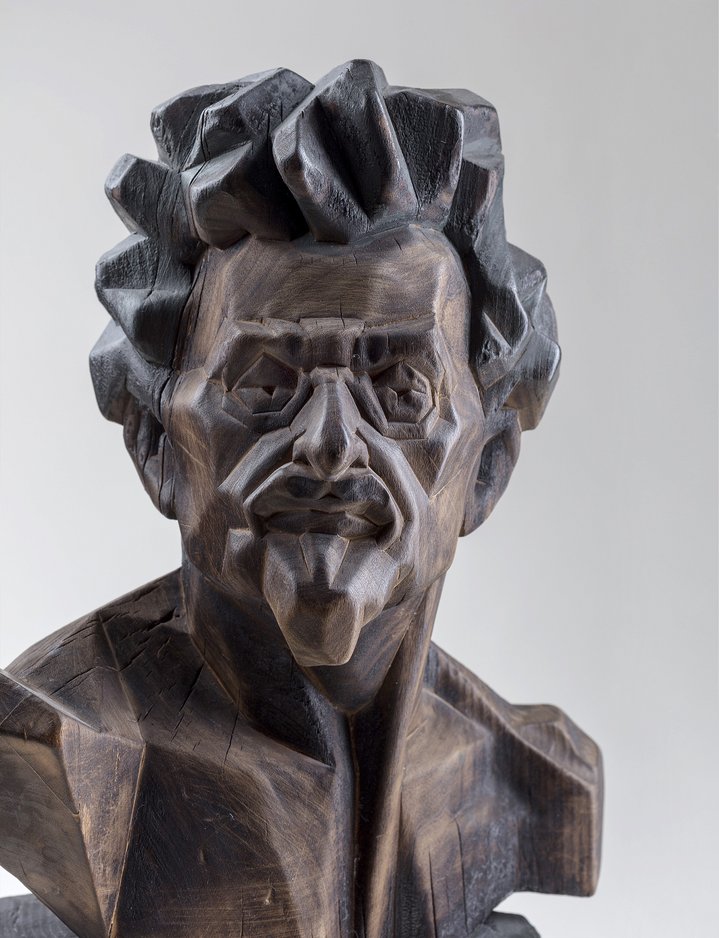

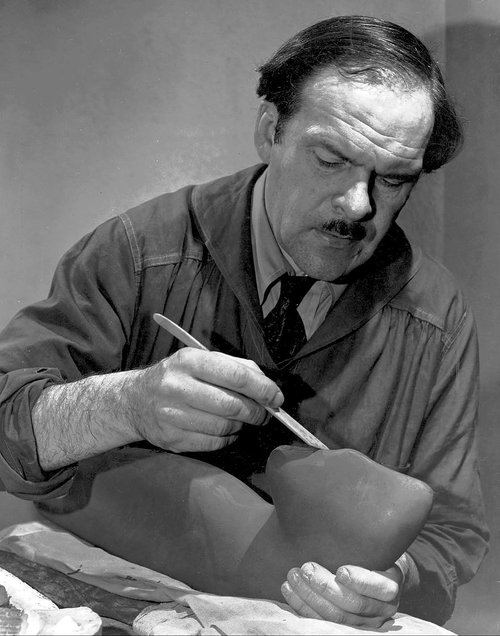

The curators challenge both time and space, eschewing a traditional, chronological approach which even spills over to the architecture of the building, a neo-classical former riding school. The exhibition design is by native architect Ingmar Vetvitsky, who turns the Manege in a kind of no-space stripping away any existing context. Podiums are covered in beige fabric and the existing interior architecture is hidden behind temporary beige walls. “We stripped the space of every architectural element, to let sculpture speak for itself, because in the 20th century sculpture does not speak – it screams!”. The show’s most powerful section ‘Special Effects’, featuring works of Anna Golubkina (1864–1927), Sergey Konenkov (1974–1971), Ernst Neizvestny (1925–2016), Stepan Erzya (1876–1959), and Ivan Shadr (1881–1961) is dedicated to their attempts to depict wild motion and loss of balance in sculpture, almost defying the very laws of physics in their desire to overcome the static nature of their craft.

Sculpture, perhaps the most powerful tool of visual propaganda before television, is intimately connected with history and the show is punctuated by works that, stripped from the ideological context of their respective eras, give contemporary visitors food for thought rather than any answers. The show opens with a 1937 work by Nina Bass-Goldman’s (1893-1990), a bas-relief portrait of Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861), a former serf and an avid patriot of his oppressed homeland, included in the Soviet pantheon of ‘progressive’ 19th-century writers and poets. A 1920s model of a modernist monument to Leo Trotzky by an unknown sculptor is placed side-by-side with a life-like Socialist Realist portrait of Genrikh Yagoda, a founders of the Gulag, arrested and shot in 1937. He is depicted studying the map of Belomorkanal, an infamous Soviet construction project on an epic scale, where 12,000 prisoners tragically lost their lives due to hunger and inhumane work conditions. Both Trotzky and Yagoda were both architects and victims of the Communist regime, once deemed worthy of monuments and later erased from history books or scratched out of group photographs of the era. Indirectly, the exhibition shows how historical concepts and narratives constantly change over time, even when they are carved in stone.

Interlinking of Forms. Russian Sculpture. 20th century

Manege Central Exhibition Hall

St. Petersburg, Russia

12 October – 3 December, 2023