A New Book Sheds Light on 1922 Exhibition of Russian Art in Berlin

A collection of essays on the ‘First Russian Art Exhibition’ in Berlin is particularly relevant today when ‘Russian-ness’ is being rethought and Berlin has become a new home for exiled artists from Russia.

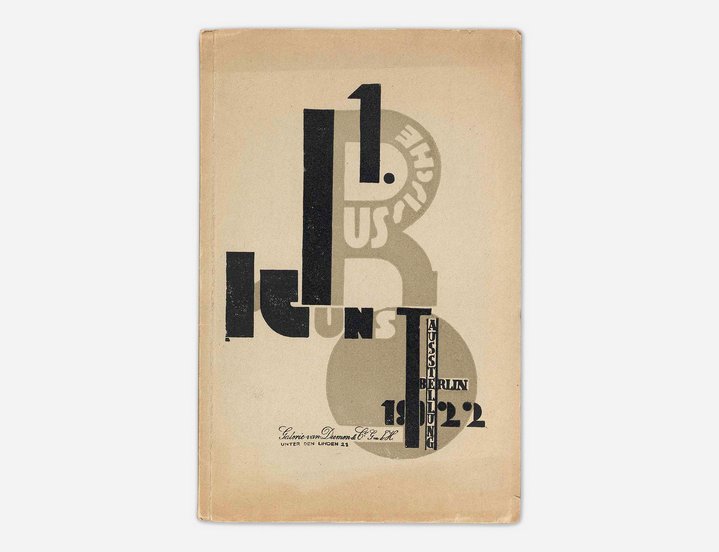

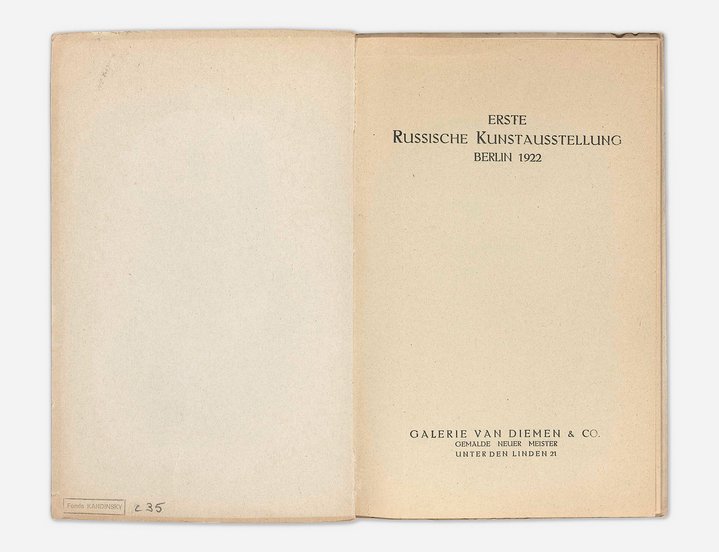

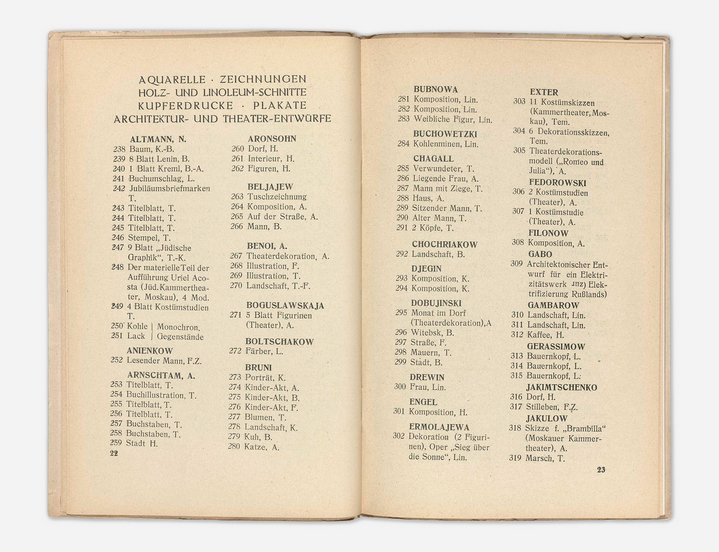

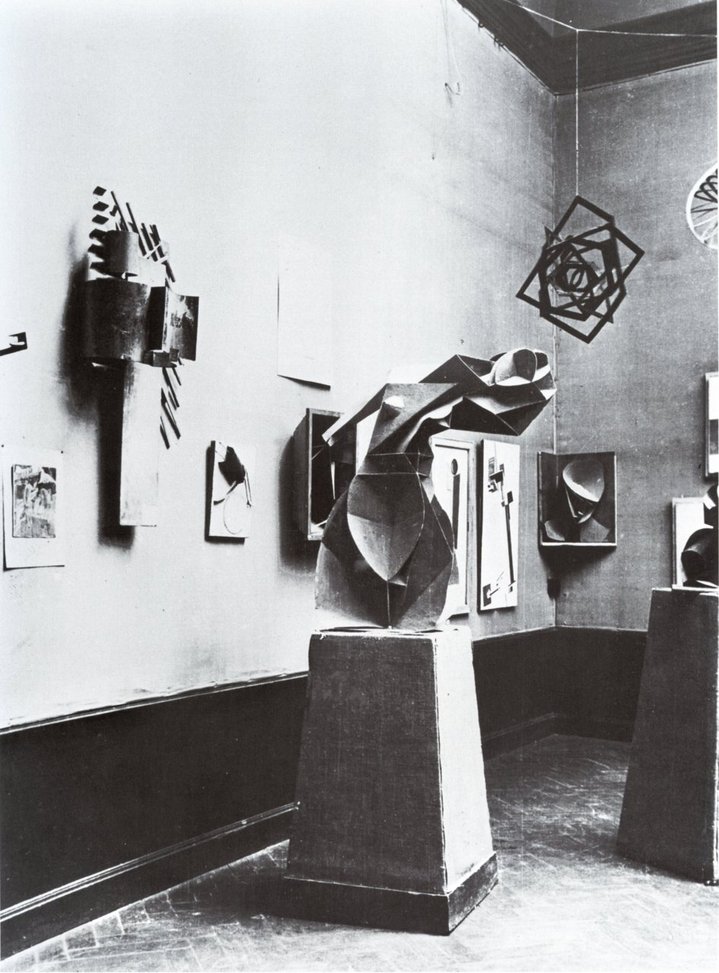

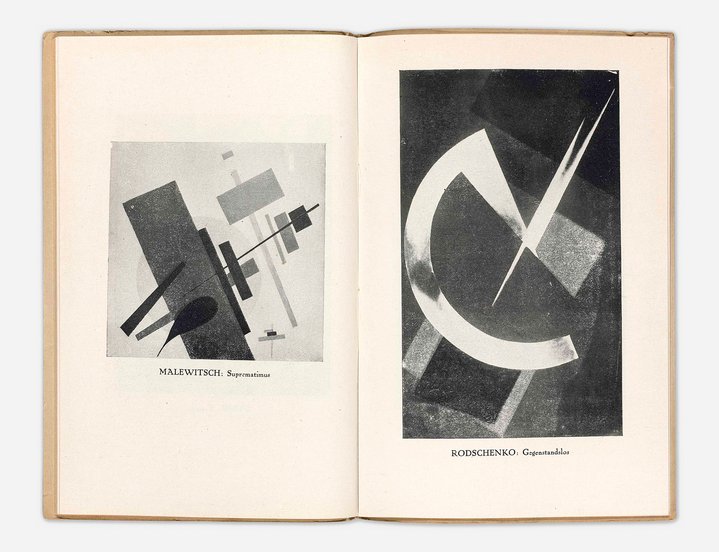

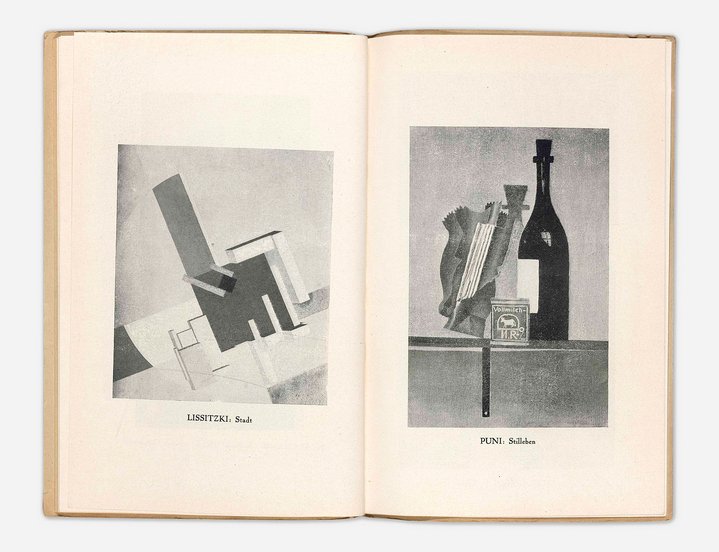

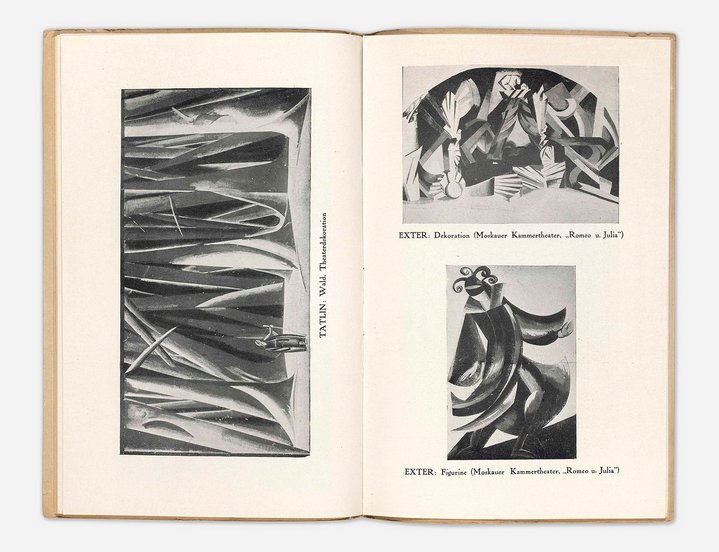

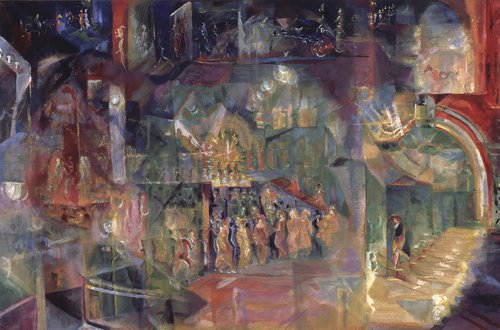

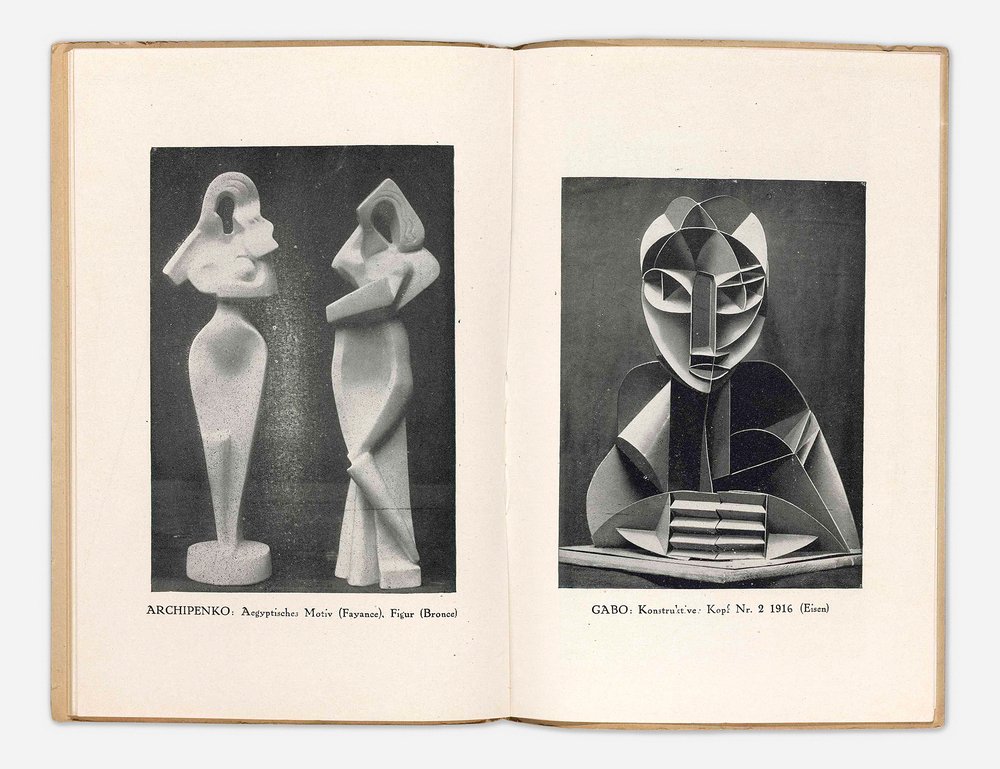

‘The First Russian Art Exhibition’ opened just over one century ago in Berlin on 15 October 1922 in the Van Diemen Gallery, an extremely ambitious undertaking which brought together over seven hundred paintings, drawings and sculptures, stage sets and architectural models. They were by artists from various countries that had once been part of the Russian Empire, but which by 1922 had merged to form the Soviet Union. Artists such as Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), Aristarkh Lentulov (1882–1943), Lyubov Popova (1889–1924), Nadezhda Udaltsova (1885–1961), Olga Rozanova (1886–1918), Marc Chagall (1887–1985) and many others took part in the exhibition. Some had already been shown to the German public at the Blue Rider group exhibitions and at Herwarth Walden’s Der Sturm gallery. However, this show of the avant-garde was on a completely different scale, some of the meanings behind it and the consequences that came from it are obvious and others are less self evident.

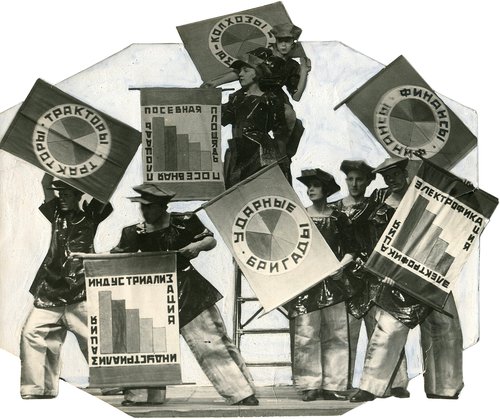

On the eve of the centenary of the exhibition's opening in October 2021, a conference was held at the Berlin State Library, which resulted a year later in a collection of articles, both thoughtful and problematic research publications written by experts from various countries, outlining the contours of this significant exhibition from many different angles. Important as a broad celebration of the art of the country of a victorious proletariat, as a gesture of cultural diplomacy and, additionally, as a crucial step towards an artist-led formation of the identity of the fledgling Soviet country abroad. Not least of all, though, as a counterbalance to the activities of the Russian émigré community in Europe, who were claiming that the revolution had destroyed art along with the old order.

Upon the question of identity, problems quickly arise around the exhibition's positioning as the ‘first Russian’. As Professor Miroslava Mudrak from Ohio University points out in her introduction to the book, the exhibition was assembled and staged not only by the participants but also by people from Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia and elsewhere. As Monika Ruethers notes in another text, many did not identify themselves as Russians, but as Jews, for example. Ulrich Schmied, in his polemical article ‘What did 'Russian' mean in the Early Twentieth Century’, notes that [in 1922] "'Russian' was perceived not in ethnic or cultural terms but as referring to the territory of the fallen Russian Empire. The blurring of national allegiances did not just apply to the exhibition itself, but also to some of the participating artists”. Nevertheless, at the very beginning of this collection of essays, a position is expressed which is consonant with the current debates unfolding over the past two years on the need to redefine the concept of ‘Russian culture’ and the ‘Russian Avant-Garde’. It’s an urgency which cannot be ignored today. These questions are outlined in the first group of articles in the collection, and a satisfactory answer has yet to be found.

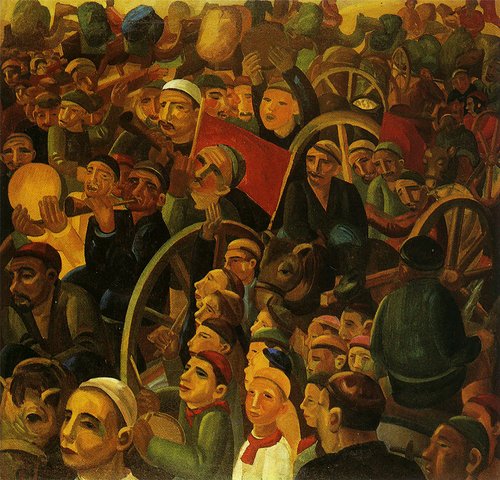

The exhibition was driven not just by questions of identity. There were pragmatic considerations: in the 1920s a devastating famine was raging across the Soviet Union and the exhibition was conceived as an opportunity to raise funds to give to the hungry by selling the works; it was not by chance that the venue chosen in Berlin was a commercial art gallery. The exhibition was preceded by a major solidarity campaign driven by German Communist Willi Münzenberg, who attracted artists to the cause like Käthe Kollwitz (1967–1945) and George Grosz (1893–1959).

Against this background, and because of the political decisions and jostling of agendas and interests during the preparation of the exhibition, it took on political overtones, becoming a tool for restoring relations between Germany and the Soviet Union. Academics Kasper Brasken and Ewa Berard address the politics behind the organization of the ‘First Russian Art Exhibition’ in their articles in the second section of the book.

The third section of texts is devoted to the reception of the exhibition and its aftermath. German critical reaction was mixed. The German magazine Das Kunstblatt called it a “disappointment”, claiming that the participants were more interested in ideology than in art and that “Russian artists ‘have more to say than to show’”. The pro-communist press criticized the exhibition for a lack of proper representation of working class art. After Berlin the works which remained unsold from the show travelled on to Amsterdam and there Dutch critics were even more harsh considering Russian art secondary to French and Dutch art and dubbing Russia “an art province of France”.

It was the Suprematists and Constructivists who attracted the most interest at the exhibition. They were noticed not only by the Hungarian Avant-Garde artist Lajos Kassak (1887–1967), but also by the German-American artist and curator Katherine S. Dreier (1877–1952), who bought several works directly from the exhibition and thus crucially paved the way for the Soviet Avant-Garde to enter North American museums.

The book concludes with scrupulous archival research by Iryna Makedon and Dilyara Sadykova, who trace the history of some works from the exhibition into Ukrainian art collections, as well as into the National Museum of Arts in Azerbaijan. Natalia Avtonomova has carefully studied the documents left over from the exhibition and helpfully offers alternative dating and attribution of some erroneously catalogued works in Russian collections. As an epilogue to the book, Ilya Doronchenkov writes about ‘The International of Art’ magazine, which was conceived in 1919 and never published; together with Tatlin's 1920 unrealised Tower project, it entered the archive of ‘utopian art’ at a time when, “the reality of the post-war artistic process denied the utopian expectations of the Russian Futurists. The international initiatives of the Left Front of Art (LEF) were much more pragmatic and politically charged.”

The book is richly illustrated and, in addition to the articles, includes a selection of archival materials which show what works of the Russian - or Ukrainian or Belarusian? - Avant-Garde were actually seen by the public in those years and how they were received by them. Collected under one cover, they will no doubt shed light on the perception of these works today and the kind of art history that can be written on their basis.

100 Years On: Revisiting the First Russian Art Exhibition of 1922. Edited by Isabel Wuensche and Miriam Leimer

Wien, Koeln, 2022