A Major Survey of Ukrainian Art in Dresden

Kaleidoscope of (Hi)stories. Ukrainian Art 1912–2023. Exhibition view. Dresden, 2023. Courtesy of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photo by Iona Dutz

Dresden’s Albertinum is staging an exhibition which explores the art of Ukraine from 1912 to the present. It is remarkable both for what it offers and what it lacks, says art critic Vladimir Dudchenko.

Many Ukrainian exhibitions have sprouted up around the world since early Spring 2022. The strength and honour of its people is drawing attention to their art. But museum shows normally are scheduled years in advance, demanding extensive research, complex arrangements with other museums and major collections, as well as the securing of funds; the large show at the Albertinum in Dresden appears to be the first in Germany. Offering over one hundred works by fifty artists from various regions of Ukraine, there is also an extensive events program, with lectures, concerts and special tours.

The Dresden exhibition opened in May, and in early June the Ludwig Museum in Cologne unveiled a touring show on Ukrainian Modernism called ‘Here and Now’ which will run until late September. It was first shown under a different title, ‘In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s’ at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid.

The political struggle that Ukraine is undergoing includes efforts in describing its own artistic history not as part of a larger imperial discourse, but an independent narrative. The latter includes artists born in Ukraine, those who have worked there and delivered a major influence, and those who have emigrated and later won international acclaim. Artists previously dubbed as Russian, French or Jewish are now perceived through a more subtle lens.

The curators in Dresden had an ambitious task in front of them. The preamble at the beginning of the exhibition space includes billboards with a take on the 112 years of Ukrainian art history that are the scope of the exposition, complete with screens and headphones. These are focused on certain dates, like ‘1927: Climax of Modernity’, ‘1937: Executed Renaissance’, ‘1968: A View of Freedom’, and so on. Some of these titles are already becoming brand names of their own. But then, the show itself is largely tilted in the direction of just the last thirty-two years of Ukrainian art, since the country has gained independence. The artworks are not placed in chronological order; the exhibition looks more like a set of extemporal cross influences. Four major themes are offered: ‘Practices of Resistance’, ‘Culture of Memory’, ‘Spaces of Freedom’ and ‘Thought on the Future’. This resembles the capsular structure that worked well recently, for instance, at the latest Venice biennale. But here the capsules are way less thoroughly outlined.

The first work that visitors encounter when entering the exhibition hall are the ‘Palianytsia’ (‘Loaves of Bread’, 2022) by Zhanna Kadyrova (b. 1981). The artist works a lot with stone. Here likewise, the loaves and slices are made from round river stones from Transcarpathia, serving simultaneously as literally ‘motherland soil’ and a symbol of life and love. These are surrounded by works by the classic Oksana Pavlenko (1896–1991), including her 1920 ‘Girl with Apples’. Pavlenko was a student of Mykhailo Boychuk (1882–1937) and inherited his line of modernism, infused with byzantine iconography. Next to it is the work ‘Shift Change’ painted in 1927 by another classic Viktor Palmov (1888–1929), adherent of Moscow’s LEF circle and inventor of his own style that he called Colourfulness. Next are a pair of stone boots by the young artist Mykola Ridnyi (b. 1985) called ‘Water Wears Away the Stone’ from 2013 - he actually sculpted these objects with a high pressure water gun. And so on...

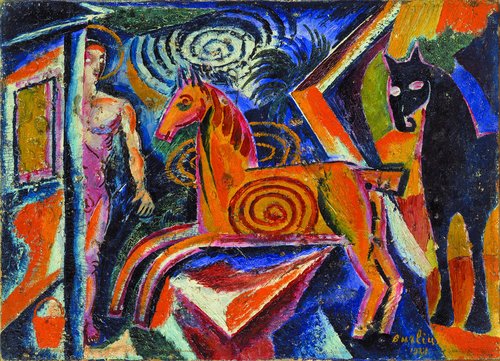

What is good about this exhibition is that the curators attempted to combine old with the new, making them work together. There are some names lesser known to international viewers which were introduced alongside the more acclaimed, like Boris Mikhailov (b. 1938), who has works in three different areas in the exhibition hall, including several pieces from the ‘Yesterday’s Sandwiches’ and ‘Crimean Snobbism’ series’ and a photographic portrait of a protester taken at Kyiv’s Maidan square in 2014. The other famous Ukrainian photographer is Sergey Bratkov (b. 1960), showing several of his earlier works and the installation ‘Quitting Smoking’ (1995–2022). These Kharkiv artists are accompanied or counterweighted by Andrij Bojarov (b. 1961) from Lviv and Sasha Kurmaz (b. 1986) from Kyiv. Kurmaz normally works with found imagery, and now has given us a striking example of how Russia’s military aggression can be shown in art in the form of a hand-made visual diary called ‘The Red Horse’, which since 2022 is ongoing.

Efforts to bring more Ukrainian names into the broader context must be applauded. The installation ‘The Possessed Can Also Witness at Court (Version III)’ by Nikita Kadan (b. 1982) created this year represents a series of shelves with small Soviet-era monuments and objects torn apart by bombings, which closely resembles the endless cases with small, labelled scuptures on the same floor of the Museum - both are references to cabinets of curiosities. Stas Volyazlovsky (1971–2018), who worked with biros on cloth, is represented by just one pillow-like object called ‘Identity Diffusion’, (2006–2016). There is sometimes the sense that the exhibition consists of works that were actually available.

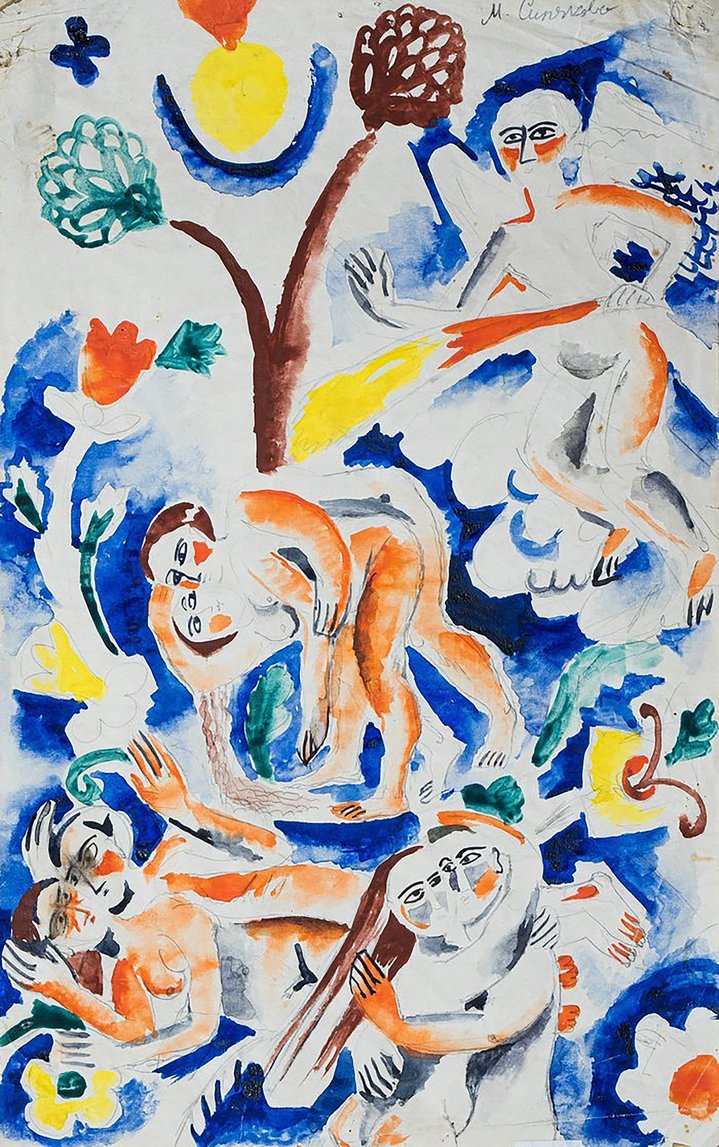

The distance between the texts and the exhibition itself is somewhat discouraging. There is no real connection with the historical periods set out for the viewer at the beginning, the artists named there and shown are largely different. Curators state their dislike for the role of the decorative arts ghetto that was assigned to Soviet Ukraine. They appeal to Oleksandr Bohomazov (1880–1930) and Mykhailo Boychuk. Ukrianian modernism and constructivism were heroic, true, only these parts are not on display. The preference is given exactly to the more decorative works, which actually look very convincing. Back in 2007 Moscow’s PROUN gallery opened with the exhibition ‘Peasants. Post-Suprematic Epos’ that clearly showed the Ukrainian ethnographic visual roots in Malevich’s works. So placing an emphasis on the decorative part of the avant-garde may be a big Ukrainian ‘thing’. Only it was not really reflected in the texts. The works by Oksana Pavlenko, Viktor Palmov, Vasyl Yermilov (1894–1968), Katerina Bilokur (1900–1961), Maria Siniakova (1890–1984) and Maria Prymachenko (1908–1997) would deserve as much.

There are certain Ukrainian brands in art, and more are being introduced with these new museum shows. One of the latest in the line was ‘Retrotopia. Design for Socialist Spaces’ in Berlin’s Kunstgewerbemuseum. It highlighted the tradition of stained glass design in Soviet Ukraine as an important and distinctive factor. These works are also the first to really bear the mark of destruction, both by time and by Russia’s bombings. Now it would only look natural to appeal to this school in general. Albertinum offers a glass mosaic of Anna Horska (1929–1970), the ‘Young Guard’, but does not reflect on the wider tradition.

On the other hand, a wall is given over to Odessan Conceptualism. It has been shown as a brand on various occasions in Ukraine for some years now. Artists that actually come from the city, including Yuri Leiderman (b. 1963) and Sergey Anufriev (b. 1964) are being conceptualized as a part of a school connected with the city.

There is an interesting view of the future evoked by the work of Feodosiy (Fedir) Tetyanych (1942–2007), who built science/art concepts of Biotechnospheres way back in the 1970s. His nearly abstract drawings and paintings are about different peoples settling across our universe, and resemble the designs of futuristic orbital stations from an era characterised by technological optimistism as well as contemporary works by Tomas Saraceno (b. 1973).

It is a pity that no catalogue has been published to accompany the exhibition and that no explanations are offered in English, only German and Ukrainian. This show actually lifts a veil off Ukrainian art as a living whole. It is made obvious just how much there is to explore and admire. These visual kaleidoscopes should be made known to as wide an audience as possible, and English texts would help. We can only hope that this exhibition is just the first step in the direction of a long-term presence of Ukrainian art in museums around the world.

Kaleidoscope of (Hi)stories. Ukrainian Art 1912–2023

Dresden, Germany

6 May – 10 September, 2023