The Ill-Fated Poet of the Absurd: Remembering Kharms in St Petersburg

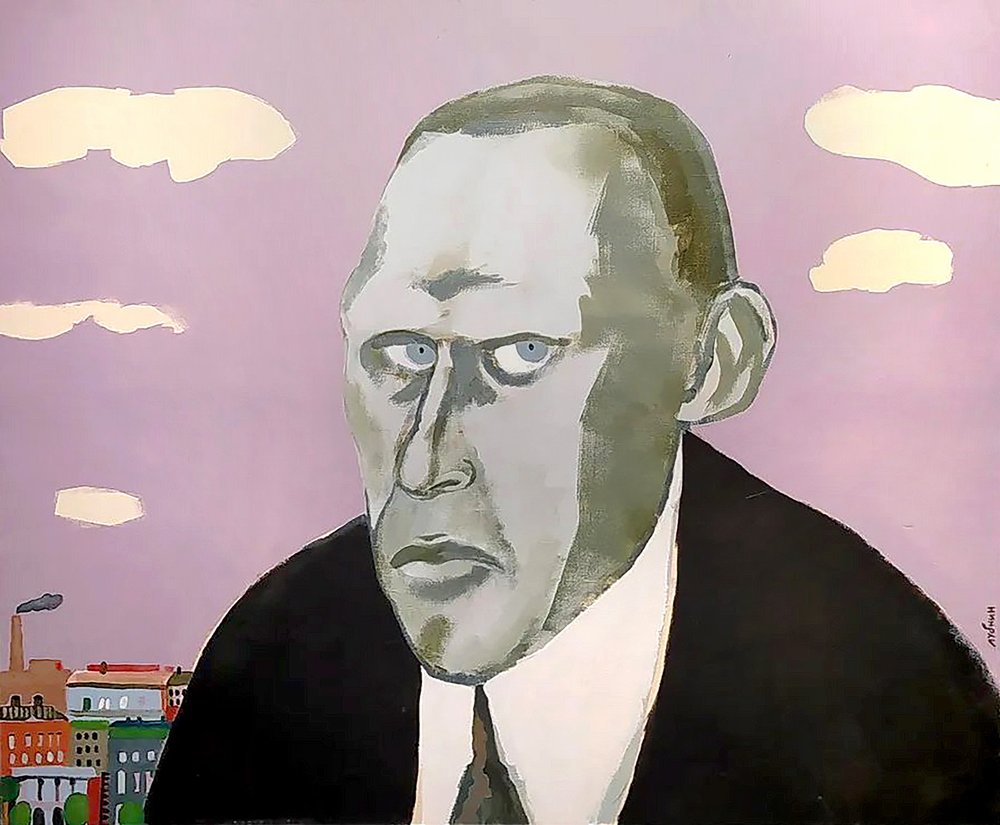

Gavriil Lubnin. Portrait of Daniil Kharms. Private collection, St Petersburg. Courtesy of KGallery

A fascinating exhibition titled ´Why, Why Am I the Best of All?´ at the KGallery in St Petersburg is dedicated to Daniil Kharms and his circle, and next year a literary and memorial museum is due to open in the former flat of poet Alexander Vvedensky.

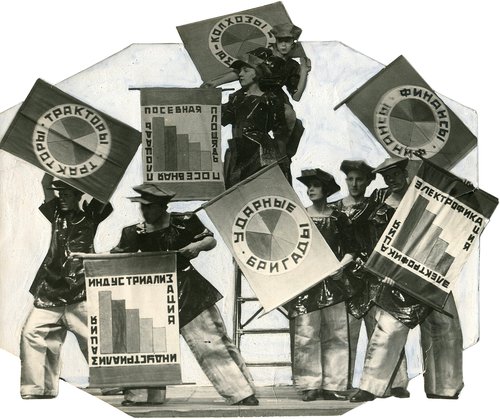

On 24 January 1928, a literary evening under the title of ´Three Left Hours´ took place at the House of Print on the Fontanka River. Writers Daniil Kharms (1905–1942), Alexander Vvedensky (1904 –1941), Nikolai Zabolotsky (1903–1958), and Konstantin Vaginov (1899–1934), together with their friends and collaborators, proclaimed the formation of a new artistic group called OBERIU, an acronym for the Society for Real Art. The poster for the event was designed by Lev Yudin (1903–1941) and Vera Ermolaeva (1893–1937), using typographic elements in a distinctive Futurist style. In the group’s manifesto Kharms wrote: “We don’t understand why Filonov’s school has been pushed out of the Academy, why Malevich cannot develop his architectural work in the USSR, or why Terentyev’s The Inspector General was booed so absurdly. We don’t understand why so-called leftist art, with all its achievements and merits, is regarded as hopeless junk — or worse, as charlatanry.”

By 1928, such questions in the Soviet Union were evidently rhetorical and filled with despair. Swiss literary scholar Jean-Philippe Jaccard, in his monograph ´Daniil Kharms and the End of the Russian Avant-Garde´, refers to OBERIU as “the last battle of honour of the Russian avant-garde.”

Kharms and his friends were the youngest representatives of leftist art: in 1925, when a close-knit group of like-minded artists formed, most of them had just turned 20. All were actively engaged in writing literature and sought allies within the artistic community — fittingly, the groups that preceded OBERIU bore names like ´The Left Wing´ or ´The Academy of Left Classics´.

On 9 April 1927, a year before OBERIU’s famous public debut, Terentyev staged Nikolai Gogol’s classic 19th century play ´The Inspector General´ in the same venue. Costumes and set design were created by artists of the Masters of Analytical Art school under Filonov’s direction. On stage large cupboards symbolized bureaucracy and some of the action unfolded inside them. One of these cupboards was later repurposed by the OBERIU poets for the ´Three Left Hours´ - pushed onto the stage with some difficulty, Vvedensky dangled his legs from the top, and Kharms read poems from the inside. One of OBERIU’s slogans — Art is a cupboard — pointed to the shared concreteness and inescapable reality of both art and physical objects.

Kharms believed that “Poems should be written in such a way that if you throw one through a window, the glass will shatter.” A debate which had been planned to follow ´Three Left Hours´ never materialised. Invited to take part were Malevich, Filonov, and Vyacheslav Pakulin (1900–1951), leaders of three major Leningrad visual art movements of the late 1920s: UNOVIS, the Masters of Analytical Art, and the Circle of Artists, respectively.

The poetry of Nikolai Oleynikov (1898–1937) and Nikolai Zabolotsky, with its focus on the biological microscopic world, can be viewed as an ekphrasis of Filonov’s art. Kharms, by contrast, was much closer to Malevich’s Suprematism, as evidenced by many of his drawings in diaries and notebooks — including the well-known ‘Self-Portrait Behind a Window. 20 May 1933,’ depicting a dark figure with a rhomboid face, lacking eyes or a mouth, behind the crossbars of a window frame, rendered in dense, multidirectional pencil strokes.

In the autumn of 1926, Kharms and his friends formed a theatre troupe called Radix and approached GINKhUK (the State Institute of Artistic Culture), directed by Malevich, to secure a rehearsal space for their play ´My Mum Is Covered in Clocks´, written by Kharms and Vvedensky (the script has sadly not survived). Malevich’s response, “I’m an old freak, you’re young – let’s see what happens”, was an enthusiastic yes.

Kharms was a frequent guest at Malevich’s home. According to the memoirs of writer Nikolai Khardzhiev (1903–1996), “Malevich’s mother, Ludwiga Alexandrovna, gave Kharms and me woollen ties she’d knitted, decorated with Suprematist designs. We wore them constantly, until they wore through.” In February 1927, Malevich inscribed a book for Kharms: “Go forth and stop progress”, gifting him a copy of ´God Is Not Cast Down: Art, Church, Factory´.

In 1932, Kharms sketched Malevich’s ‘Three Female Figures’ in his diary. The painting was then shown at the ‘Artists of the RSFSR: 15 Years’ exhibition at the State Russian Museum which was to be the last public display of avant-garde art for a very long time. The painting was exhibited in a lavishly gilded frame, an example of the “slightly flawed equilibrium” that Kharms found intriguing. He described this as: “An antique marble statue of Venus with a beautifully sculpted marble wart on her lovely leg.”

In 1935, Kharms composed a poem dedicated to Malevich, which he read aloud at the artist’s memorial service. The text reads like an incantation:

Of memories breaking the stream,

you’re looking around, your face having with proud distressed.

The name for thee — Kazimir.

You’re watching the wane of the sun of salvation for thee.

From beauty supposedly the mountains of your land are destroyed.

No basement to hold up the figure of thee.

Give me the eyes of thee! I’ll unblock the window on my head!

As an artist, Kharms stood firmly within the Futurist tradition. His notebooks, filled with sketches alongside drafts of texts and daily notes, are an inseparable part of his poetic legacy — they form a single entity with his literary work. In 2006, a book titled ´Kharms’ Drawings´ was published in St Petersburg. In their essay on Kharms’s notebooks, artist Yuri Alexandrov (b. 1949) and literary scholar Anatoly Barzakh wrote: “Kharms does not so much create something unprecedented or build a new world – as the avant-garde artists did – but rather constructs a collage from ready-made objects, much like the stationery notebook that contains them. And yet all this becomes a unified aesthetic object – endlessly fragmented, hideously chaotic – but nonetheless whole. And it is precisely the presence of Kharms’s ‘texts’ from within that holds this chaos together.”

In his notebooks, Kharms left behind film scripts which were almost fully developed, storyboards for graphic novels and comic strips, and ideas for art happenings and performances. The film ´Meat Grinder´, shown at the ´Three Left Hours´ evening (now lost), has been likened to contemporary video art and the ´parallel cinema´ of Gleb Aleinikov (b. 1966) and Igor Aleinikov (b. 1962-1994). Director Klimentiy Mintz (1908-1995) assembled found footage into a kind of pacifist montage with endless trainloads of soldiers passing across the screen at increasing speed. Kharms and artist Alisa Poret (1902–1984), a member of the Filonov school and his close personal and creative partner, collaborated on costumed portrait photographs reminiscent of work later done by Yasumasa Morimura (b. 1951), David McDermott (b. 1952) and Peter McGough (b. 1958), and Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe (1969–2013).

Alisa Poret was just one among a large circle of young artists recruited into children’s literature by the poet Samuil Marshak and artist Vladimir Lebedev (1891–1967). The children’s books and magazines Chizh (´Exceptionally Interesting Journal´, 1930–1941) and Yozh (´Monthly Journal´, 1925–1935) featured artists who are now considered the most important figures in 20th century Russian graphic art including Nikolai Lapshin (1885–1942), Nikolai Tyrsa (1887–1942) and Nikolai Radlov (1889–1942). The OBERIU writers were frequent contributors to these journals until the 1932 crackdown on the “anti-Soviet group of writers”, though their children’s work continued to be published throughout the 1930s.

Daniil Kharms, Alexander Vvedensky, Nikolai Oleynikov, and Nikolai Zabolotsky were all subjected to repression. Oleynikov was executed in 1937, Zabolotsky was sent to a labour camp in 1938 and released in 1956, Vvedensky was arrested in 1941 and died in Kazan en route to labour camp; and Kharms was committed to a mpsychiatric prison hospital in Leningrad, where he died in 1942.

It was children´s literature and humorous verse that saw the eventual revival of Kharms’ legacy. In the early 1960s, philosopher Yakov Druskin, a friend and ally of the deceased poets who had rescued Kharms’ manuscripts from his flat which was bombed out in 1942, began sharing his archive within a small group of academics. The aesthetic shock caused by these texts was such that uncensored Russian culture in the 60s and 70s could be called the era of Kharms and the OBERIU. One reader was artist Mikhail Chemiakin (b. 1943), who frequented Druskin’s home and painted his well-known portrait. In the Paris-based almanac *Apollon-77*, published by Chemiakin, major works by Vvedensky were printed with illustrations by the artist, alongside poems by Kharms and Konstantin Vaginov. These shared pages with verses by living underground Russian poets.

In the following decades, Kharms was embraced by non-conformist Russian artists both as subject and symbol. The OBERIU legacy was perfectly expressed in 1982 in ´Zero Object´ by Timur Novikov (1958–2002) and Ivan Sotnikov (1961–2015), who designated a rectangular gap in a display panel as an art object and, in the spirit of Duchamp, claimed authorship. As art historian Ekaterina Andreeva notes, “The decree of Novikov and Sotnikov to substitute the zero with a nought echoes Kharms’ essay ‘Zero and Nought’, which they had not read. A comparison of these texts highlights the ‘nullification’ of avant-garde infinity in the absurdism of the 1970s.”

The Kharmsian theme found vivid expression in the works on paper, lithographs and art books by St Petersburg artist Mikhail Karasik (1953–2017). He initiated the Kharms Festival in St Petersburg which consisted of theatrical processions, literary readings and conferences and was held five times, from 1995 to 1998 and then again in 2005. In 2003, under Karasik’s publishing project Kharmsizdat, books on the Russian avant-garde were printed in limited editions of 21 copies, each illustrated by prominent Russian artists, including Vladimir Kozin (b. 1953), Boris Kudryakov (1946–2005), Pyotr Shvetsov (b. 1970), Yuri Shtapakov (b. 1958), and Sergei Yakunin (b. 1955). From the 1990s onwards, OBERIU poetry and prose has become an organic and accepted part of Russian literature and a recognized dialect of art, with young contemporary artists today having “lived with Kharms”, a testament to Kharms´ legacy which was preserved and then transmitted by a previous generation.

Why, Why Am I the Best of All? Kharms and his company

St Petersburg, Russia

5 April – 5 July, 2025