The Art of the Apartment Gallery

The exhibition of Alice Yoffe at Simon Mraz's apartment, 2015. Courtesy of RAAN

Major museums, top galleries and annual art festivals all influence cultural trends and in today’s Russia small apartment galleries are punching far beyond their weight. Artist Pyotr Bystrov (b. 1980) who co-founded an influential apartment gallery in Moscow nearly two decades ago looks closer at this phenomenon.

Since the 1970s, Russia has seen a broad proliferation of small apartment galleries, a tradition which is possibly without parallel elsewhere. Whereas in the 1970s and 1980s apartment exhibitions existed around the need for authentic, uncensored dialogue in intimate circles under conditions of total control over the ‘artistic word’, during the decades that followed this practice developed into more of a two-way dialogue between unofficial art circles and the public at large, which served to elevate the status of such apartment shows. This came at the cost of losing the authenticity of the message, deprived of soil. Then came a new round in which artists strove to make ´real´ independent art without approvals, curatorial selection, and dictate of the trends, once again in flats, dachas, and squats.

In November 2006, when Kirill Preobrazhensky (b.1970) and I founded the apartment gallery Cheremushki in Moscow, our focus was just in part on the intimacy of what was happening there, more on the latent confrontation between male and female worlds. Our exhibition debutant was Elena Kovylina (b. 1971), our choice intentionally expressed the inevitable conflict between a major figure in the official art space, such as the director of a museum, with an independent - even self-proclaimed - artistic authority, the female artist being here a kind of ‘housewife’ of subjective aesthetic perspective. The artworks in the show related to the implausible event of a boxing match between a woman and a man, referring to one of Kovylina's public performances, during which the artist invited people regardless of their gender, weight category and degree of training, to fight in a boxing ring, following all the conventional rules. Taking place in the Cheremushki apartment gallery space, in what was otherwise a non-descript, small 1960s residential housing block, the opening attracted the attention of respected museum directors of leading Western institutions, such as Peter Noever, then director of the Vienna Museum of Applied and Contemporary Art, who immediately selected several of Kovylina's works to be exhibited in the public space of the Austrian museum.

Today whether social, economic or professional, relations are largely built on the principles of merger and acquisitionbetween small and large, niche and fashionable, local and global, and the art world is no exception. The recruitment of an independent garage musician by a major record label, while undoubtedly opening up commercial and career prospects, at the same time deprives the sound of its original authenticity. Nowadays, an artist, musician or actor is perfectly able to set the right accent needed, even if sacrificing authentic creation, to engage with the public in an official setting if necessary for his or her career.

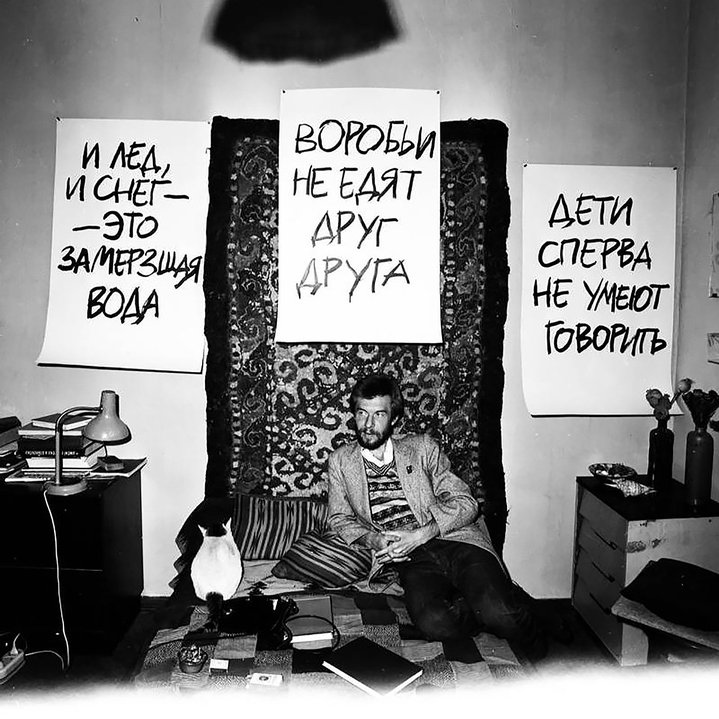

A classic, historical example within the tradition of apartment art is the APTART project by artist Nikita Alexeev (1953–2021) where the term itself is a blend of the English word for ‘apartment’ with ‘art’. Back then, in the early 1980s, organising exhibitions in your home was the protest of young and passionate independent artists against the shackles of the state, and the ethics and aesthetics of officialism. The artistic content itself was designed to accentuate this gap, instead of a beautiful and flawless socialist ‘tomorrow’, the focus was on street junk, rubbish, and waste.

Nowadays, it is no longer a conflict between the new officialdom and a free-thinking environment, but rather the identification of an object or a work as artistic or not. Thus, a viewer goes to a museum in order to see art, to encounter the beautiful, created by the cult of craftsmanship and the authority of the name (although nowadays you can often see junk in museums, it is a well-established trend). An apartment exhibition bridges the gap between art and life itself, forcing the visitor to abandon the myth of the work as something beautiful and separate from everyday life, in all its ordinariness. So, the tension which comes from the idea of the unattainability and a sterile ‘high ideal’ is released.

At the same time, these days apartment galleries do not need to be untidy, in a bad state, in an old attic or a cramped basement. There are many ways to create an atmosphere of intimacy. For example, a clean and bright environment a bit like in IKEA, which stages small room settings in which you might imagine living but cannot as the cleanliness and sterility will be gone with the first sign of life.

Art historian, blogger and art collector Ekaterina Kartseva recently opened the murmure gallery in Moscow, which positions itself as a home gallery dedicated to female art. The first group exhibition ‘The House I Live In’, which brought together textile works by Maria Arendt (b. 1968), photographs by Maria Innokentyeva-Chitaeva (b. 1985), and a ‘household’ series by Natalia Konyukova (b. 1977), manifested a new female space on the map of self-organised artistic venues in Moscow. Her second show presented Anna Orekhova's painting and installation ‘Migratory Birds’ which reflected on women’s need or desire to move from one place to another and be in a constant state of migration. After this was a solo exhibition of work by Sveta Isaeva (b. 1984), organised in collaboration with the Nikolay Evdokimov gallery, also an apartment project, in St. Petersburg. All three exhibitions were made as site specific events which risk losing colour and meaning when taken out of the walls of the flat.

In the early 2000s, the ‘Gallery of One Viewer’, which became a well-known location on the map of Moscow’s art world was founded by a group of artists in a squat on Novoslobodskaya Street. According to the rules of visiting the gallery, visitors found themselves face-to-face with a work of art that was available to view for them alone during the entire exhibition. The role of the viewer as an agent and sole witness of what happened in the space was radicalised. This was an attempt to overcome the alienation felt by the crowd of spectators at a major exhibition, where people often feel as though they are part of the flow, and that the art on show is not meant for them.

As a rule, the current state of affairs in the art world at any particular time acts as a starting point from which the home gallerist builds his or her strategy and expression of personal ethics. As before, these initiatives are connected with the rethinking of creative freedom and the search for new ways of reaching the audience. Hence, for example, the exhibitions characteristic of the Moscow gallery ‘Eto ne Zdes’ (‘It's Not Here’), which are staged in a window, both literally and physically on the border of what is inside and outside. Art is on both sides of the glass, as in a window; it is art for ‘here’ and ‘there’; art that can be seen through an open window, and life through the glass from inside the room.

Another kind of domestic art space is the salon apartment, which is always in a central, prestigious location, headed up by a charismatic owner. It could be the flat of a diplomat used as a meeting place for people drawn from different spheres such as fashion, media, or business, and very young artists, as in the case of the Austrian cultural attaché Simon Mraz, who lived in Moscow for many years and organised legendary art parties in his rented apartment with a view of the Kremlin. Alternatively, there is the Moscow flat of art historian Alexander Shumov, (where artist Oleg Kulik (b. 1961) used to have his studio), a decadent space for living and meetings, which eventually hosted exhibitions, performances, readings and concerts.

There are countless variations of the apartment exhibition. The geography, architecture and anthropology of contemporary art spaces are so broad, and artists, participants and organisers are able to move around virtually unimpeded, freely changing their identity, in which homebird becomes charismatic socialite, the renegade becomes the fashionista, the artist becomes the gallerist, multiplying possibilities and varying contexts, all in a fundamental rejection of rivalry, competition and mutual exclusion.

This article was first published in the November 2023 issue of The Art Newspaper Russia.