Valery Grikovsky’s Classified Life

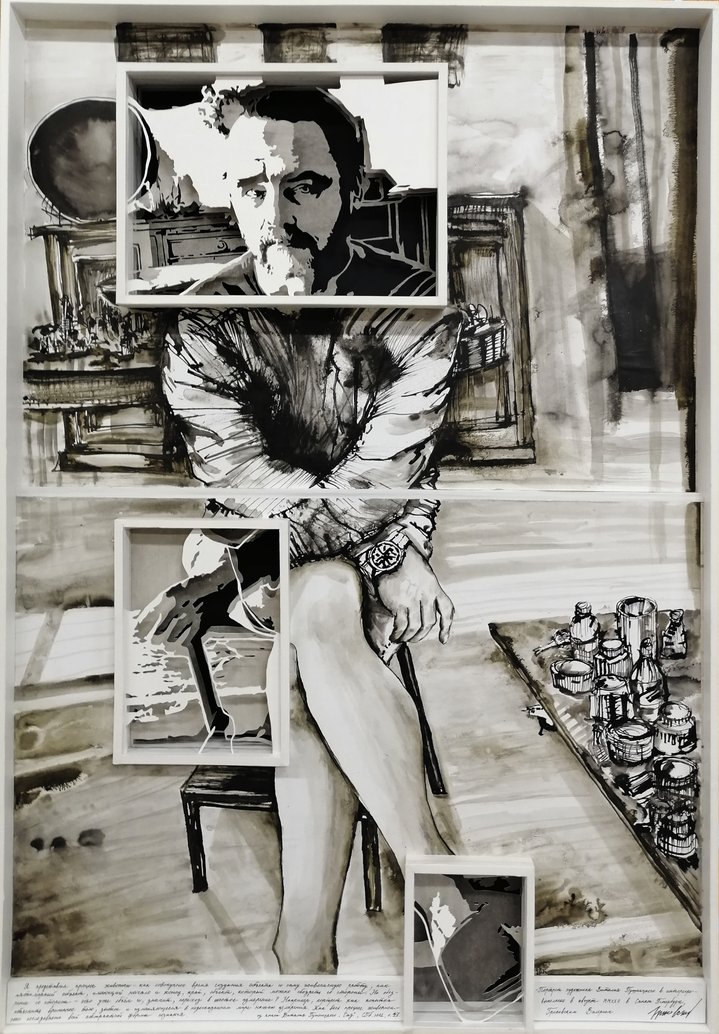

Portrait of Valery Grikovsky. Courtesy of the artist

As post-millennial informational networks may not bring us the stability we need as human beings, artist Valery Grikovsky tells writer Dimitri Pilikin how he manages to keep it all together as his latest solo show opens at the Ksenia Tarnavskaya Art Space in his home city of St Petersburg.

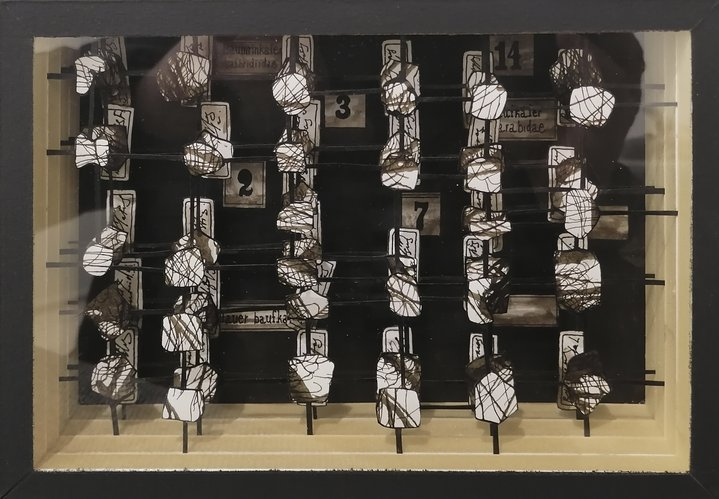

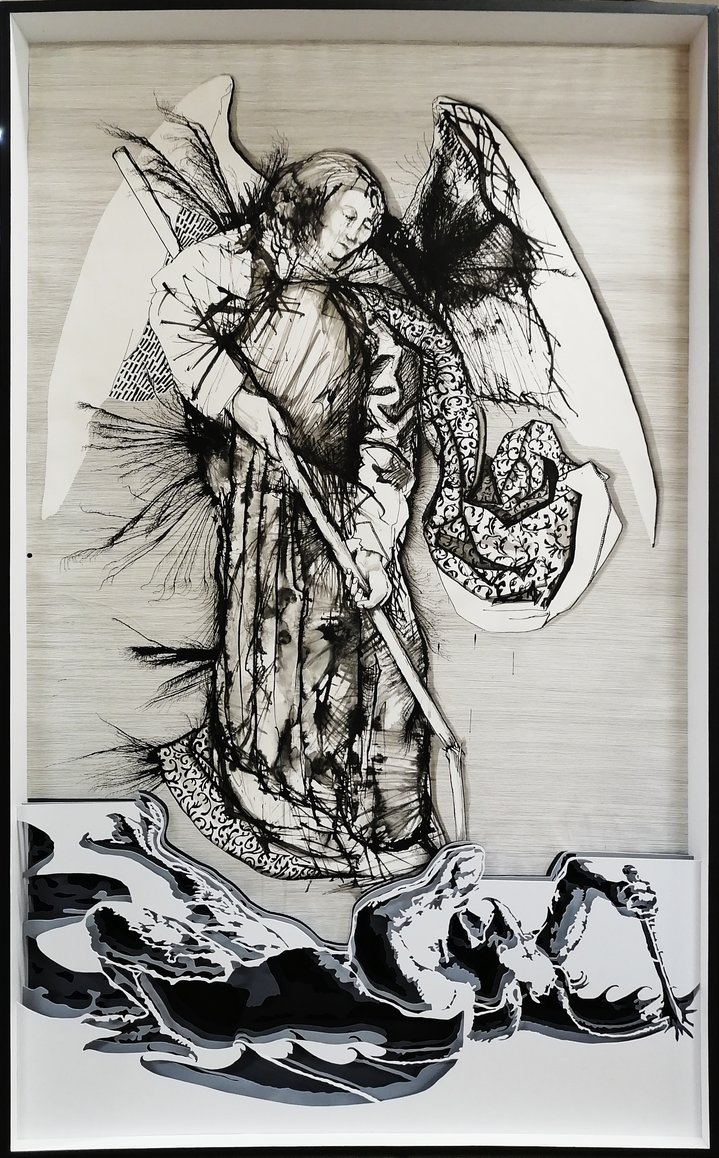

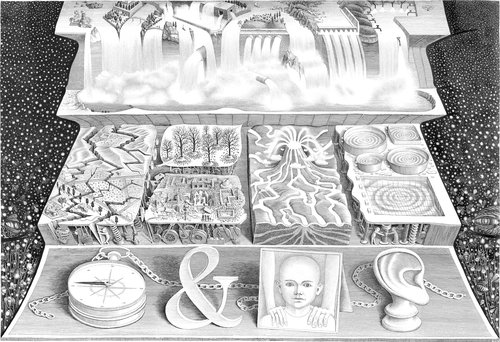

Here you can see works on paper with views of St Petersburg, sharp lines literally cutting the once familiar architecture into fragments and then rebuilding it, and drawings made into miniature 3D constructions. This is the work of 48-year-old St Petersburg artist Valery Grikovsky (b.1975) on view at Ksenia Tarnavskaya’s art space, a long-awaited solo show. The artist is having a moment in the Russian art world, almost in parallel, one of his large-scale installations ‘Scientific and Educational Collection’ is the centrepiece of a group show in Ivanovo, called ‘Congenial Interactions’. It consists of a collection of small objects and drawings which have been dissected and systematised as if according to science, yet it is art.

Written in the kind of calligraphy of traditional scientific labels, the titles of these collections he conceives and assembles are bizarre, such as ‘The Evolution of Mickey Mouse's Hearing Organs as a Result of Changes to His Image in Walt Disney Films’ or ‘Skin Changes and the Dermatology of Shrek’ or ‘Collection of Ash from Witches Burned for Heresy during the New Middle Ages’ and so on. Ridiculous you may think but ironically, the display and content of the collections is entirely sober, exuding a sense of scientific accuracy, and with visual appeal. And curiously most visitors did not just pass by, rather they stopped and spent time looking closely.

Grikovsky’s approach to art and life brings to mind Alexander Pushkin's famous phrase in the play ‘Mozart and Salieri’, ‘I measured harmony with algebra’ a reminder of the hopelessness of judging artistic creation using any fundamental, rational systems. But now, we live in fast changing times, there is a sense that we no longer understand our world, and Valery Grikovsky’s reaction to this experience of almost collective collapse is to systematise the world around him.

As the artists himself explains, "I have a medical background. I grew up with the foundations of traditional science, yet today the informational flows around me bring only fairy-tales and myths created by pseudoscientific knowledge. And people believe it! It should be about knowledge not belief. I see a cause of conflict today not only in the weakening of the role of science and education, but also in this moment of seismic transition for our entire civilisation. In general, civilisations all differ in the way they receive, collect, store and process information. It seems to me that our European (including Russian) civilisation, which was formed during the Renaissance, came to an end around the turn of the millennium. We have long been used to a model in which culture exists through a sense of continuity and consistency which reflects on and depends on history and in which all phenomena are somehow connected in ways we understand. But now, in my opinion, there is a new type of network style civilisation, in which there is no fundamental structured system of connections, and references easily get mixed up or twisted. Hence now we have a need for constant fact-checking and the need to quickly build evaluation criteria.

Everyday reality and our everyday environments now come and go much faster than the shift between one generation and the next, or the collapse of political regimes. Just take a look the contents of an antique shop or flea market in Russia or Western Europe to see how our domestic environments have been rapidly washed away by change as a result of revolution, war or huge social change. Long ago, our material world adjusted to the philosophy and practice of 'disposable objects'. What once was a respectable notion of the ‘collector’ acquired a less wholesome aspect in contemporary novels by John Fowles’ ‘The Collector’ or ‘Perfume’ by Patrick Süskind as well as a whole host of Hollywood horror movies. Personally, I think today the collector has partly come to personify psychosis. A first symptom is the presence of one's own scientific theory and the systematisation of one’s own individual worldview. Then, collecting is the passion of a gambler. The desire to possess a thing is the pursuit of an unattainable object of desire. You might think a collection which has been assembled is a dream come true, actually it is a nightmare. It turns out that the real aim of collecting is not a desire for systematisation, but an attempt to stop time, to tame reality and make it more predictable and safer. Yet unlike art, a butterfly, a flower, a shard, a fossil, a dried beetle are the most fertile objects for collecting, they lend themselves to systematisation and description, they do not argue or contradict the value judgements of a collector.

Grikovsky’s interest in collecting goes back as far as he can remember. "I have been collecting insects since I was a kid. I went to a club at the zoo, and as a student I wanted to study entomology at the Biological Faculty of the university. Later on, thinking more about my hobbies and what I liked doing, I came back to collecting. I have a large and decent collection of beetles, which is even mentioned on the website of the Zoological Institute. I collected and dissected most of them myself. I have exchanged some of them, and there are a few exotic beetles from tropical countries in my collection. The value of a beetle is not in its size or beauty, but in its rarity”.

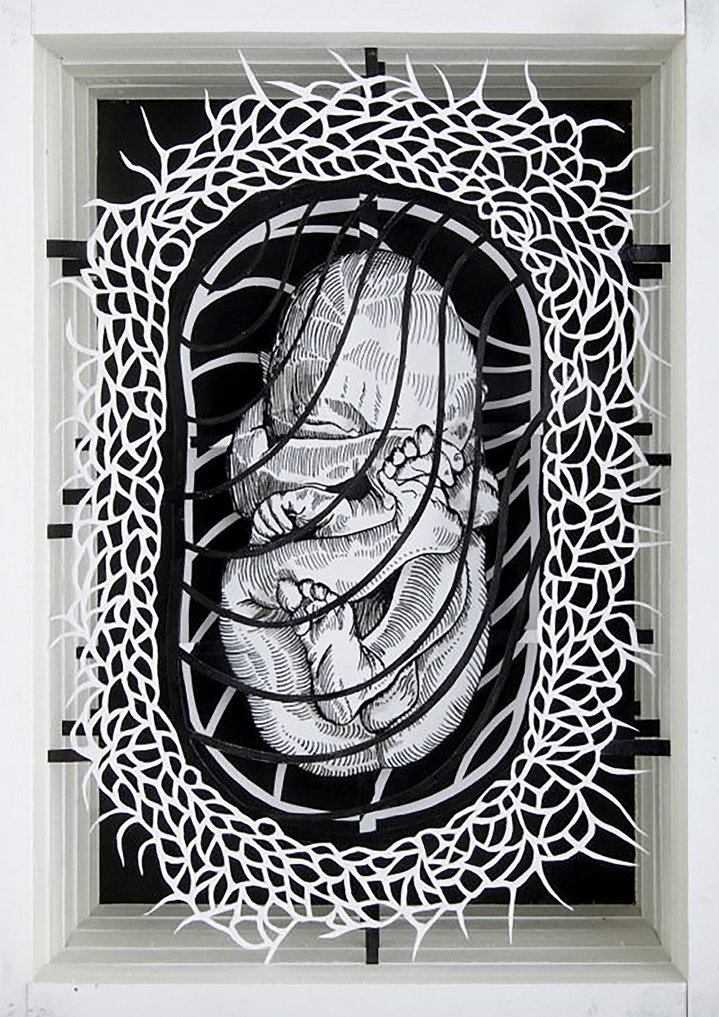

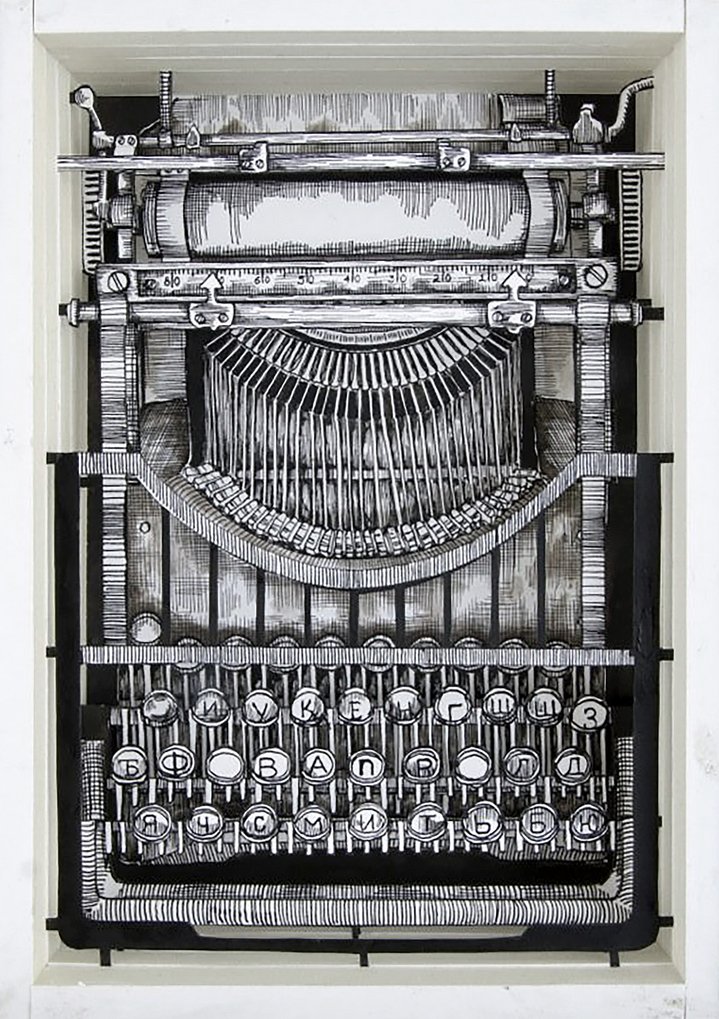

Beetles and art eventually came organically together, he recalls, “For many years as an artist I would paint pictures during the day and in the evening, I dissected beetles for my collection. However, there came a point in time when I decided to put that experience to artistic use and I began to think about creating three-dimensional objects rather than just painting. In the scientific profession we often joke about how an entomological or botanical collection is mostly just a collection of carefully written labels. Because a beetle, butterfly or plant only acquires scientific value if it is provided with accurately attributed scientific label. In a museum, an ugly looking beetle can be a valuable exhibit, while in the museum gift shop, a luxurious beetle in a frame is nothing more than a souvenir. This brings us close to the very problem of evaluating a work of art. The museum and its attribution create a frame of value for each object. But which attributes earn a work of art its place in Eternity? My drawing might be just a drawing, but if I cut it into a thousand pieces and make an object out of it, then the viewers and specialists will react differently towards it, so does it acquire some other artistic qualities? All these imponderables arose from a simple observation of a collection of beetles".

Grikovsky's signature works are graphic images divided into tiny fragments each systematically attached to a base with a pin. I think this practice comes from two sources, entomological collecting, and the art of the book. Observing them you can see that it takes literally schizophrenic powers of concentration, consistency and neatness to make them. And in addition to beetles, he also collects and meticulously restores rare, printed books. "When I was in the process of finding myself as a young man, I became fascinated with antiques and old editions of books. Mainly they were pre-revolutionary engravings, lithographs, headpieces, vignettes”. He tried and failed at working on a large scale but “for me working in miniature was like working with a petri dish, like an incubator”. He likened it to putting things inside a precious jewellery box, as he puts it, “You can't fit a landscape in there, but something scientifically collectible, entomological or botanical is quite possible”. So, a whole series appeared in a Kunstkammer format: a snail, a small rodent skull, a miniature, and then he did the same with his works on paper, cutting them into pieces. It reflected his own sense of falling apart at the time, “But my researcher's brain doesn't let this picture fall apart, I pin each piece down and reassemble it into a new total archive.”. For him it turned into a project about what he calls the fragility of culture.

Grikovsky lives in Kolomna district of St Petersburg by the Pryazhka River. The old historical centre in his neighbourhood is almost deserted and half-translucent, it seems that the city with its noise and crowds of tourists is somewhere else, and as though here nothing has changed since the 19th century. The city here rests at the mouth of the Neva River and the Gulf of Finland, the coastline is blocked by the huge industrial territory of the Admiralty Shipyards, from which the openwork tops of cranes stick out into the sky. These are the cityscapes he tirelessly depicts in his drawings. Often it is from the same view, but it is always varied. A square on Rizhsky Avenue, a path and bushes to the left and right. Paper, ink, streaks of paint. How do we look at architecture? How is it conveyed in drawings? You can hardly make out the architecture in Grikovsky’s ink shaded drawings, it seems to be covered by scaffolding. There is always a pattern hidden in this cityscape, in which basic details can be discovered and from this small fragment a new image of a whole world can be built up. In the end, it probably does not matter what is depicted, because the focus of the gaze is not on the final form, but on the process of its development. It is these cityscapes that form the core of his new exhibition ‘A Superfluous Detail’ at the Ksenia Tarnavskaya Art Space.

"I love landscapes and paint them a lot. But for me there is a clear distinction between painted landscapes and real landscapes. A painted landscape is a tree, a road or a lake. They are the protagonists. A real landscape is a square metre of land, which could be any square metre of land. And here what interests me most is a histological way of perceiving the world. Histology (ed. the study of structure and activity and development of the tissues of living organisms) is one of the most beautiful sciences, in my opinion. Tens of hundreds of different types of tissues and cells are described there, which are all evolving. Yet this diversity comes from just three embryos: ectoderm, entoderm and mesoderm. I apply a similar way of approaching landscape in my visual language where the surface of the Earth, the architecture of a cathedral or the biological tissue of a human being are contained in a single universe”.

In Grikovsky's personal archive he has a stack of albums with drawings made on his travels. He sees drawing as his real teacher, it replaced art school and allowed him to develop his own style. Early albums containing fragments of maps he has drawn, diary notes and mountain landscapes refect his passion for mountaineering and trips to the Caucasus and Altai. In other, later ones there are landscapes of Switzerland, Montenegro, Poland, Italy and Spain. On every trip he takes a notebook and drawing tools. It's a habit.

In Robert Musil’s ‘The Man Without Qualities’ the Austro-Hungarian Empire is crumbling, and as preparations are underway for the 70th anniversary of the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph I it is only the readers who know that Emperor Franz Joseph will not live to see the date and the whole narrative unfolds against the background of foolish attempts of Austrian pseudo-patriots to outdo their neighbours and rivals. During the most troubled of times, artists need to respond to the changing world and its complex questions and challenges. Grikovsky has his own thoughts about this and our present reality. "People are saying today that during wars and special military operations, art - especially contemporary art - cannot just sit on the sidelines, it must act. But it seems to me that art does not owe anyone anything. For me art is about cognition of the world and all the constituent parts of this world, including current politics, social problems, and our role as individuals in society. It is cognition, not the desire to please or to turn into a heated fighter on the barricades. We grew up on European culture, music, architecture, art, even its popular culture, Hollywood films and McDonald's, and suddenly, it has turned into ‘enemy contagion’. It is ridiculous! My world as an individual and artist is falling apart, shattering into pieces. That is why I fix each little piece of meaning I find with a pin in the hope that something new will form".

Valery Grikovsky

(open by appointment)

St. Petersburg, Russia

1 November – 31 December, 2023