Russian rural inferno as seen by its millennial artists

Danila Tkachenko. Motherland, 2017. Photography. Courtesy of the artist

The fate of Russia’s villages that have existed in limbo between life and non-existence for many years, is a preoccupation of the first post-Soviet generation of artists.

For centuries artists have gone to the country in search of inspiration. Yet for Russia’s millennials this inspiration takes a somewhat darker tone in these most anxious of times. A recent and striking recurrence of this theme can be seen in Julia Kartoshkina (b. 1985)’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Folk and Naive Art in Moscow. Professionally trained, in her work Kartoshkina re-thinks the aesthetics of what is naive or outsider art. Her brightly coloured cityscapes and seemingly amateurish homages to classics, from the Russian realist painter Valentin Serov to Henri Matisse were sold literally in their hundreds by The Ball and The Cross during the pandemic.

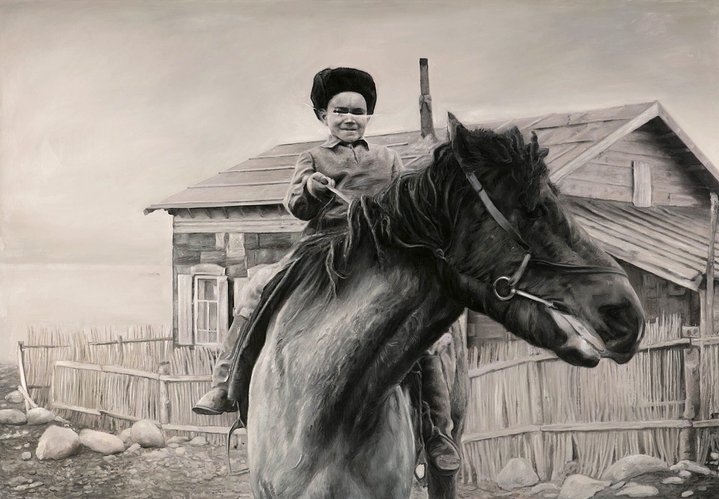

At her current exhibition ‘Hot off the Skillet’, Kartoshkina is showing earlier works from the mid 2010s which formed part of her ‘Peasant Series’. Seen by the public for the first time they are revelatory. These scenes of rural life, with old women wrapped up in shawls and cows being milked in an open field, are stripped of their mundane details, and plunged into darkness. Despite the innocent subject-matter, Kartoshkina’s works reveal life’s inner tragedy. Laconic and spiritually charged, these large drawings in pastel and acrylic on paper arrest the viewer’s gaze for their dark palette and solemn, static compositions. There are religious undertones in these works, yet they are not overt. There are subtle references to the art of the past, from ancient Russian church frescoes to the Soviet ‘austere style’ of the 1960s. Dark human figures become symbols of ill-fated humankind, in contrast with birds and animals which are rendered in red and white. She outlines the figures in bright colours, creating the impression of inner light permeating the darkness. “There is hope that overcomes the drama”, writer Elena Dunskaya has said of this body of work. According to the artist herself, these drawings, created during what was one of the psychologically darkest periods of her life, stemmed from her childhood memories of summers spent at her grandmother’s dacha in a typical Russian village on the outskirts of Moscow.

Unlike Kartoshkina, who finds spiritual power in the Russian countryside, Vasily Kononov-Gredin (b. 1990) focusses on its physical decay. His total installation ‘Russian Death’, first shown at the Art4 museum in Moscow comprised a burnt iconostasis from a village church, paintings based on enlarged negatives of snapshots made of village funerals and even a purring cat skeleton. He has photographed and filmed the exteriors and interiors of dachas in abandoned villages scattered all across the North and central-European parts of Russia. Countless villages in these great swathes of the country are slowly turning into ruins, because agriculture is economically unprofitable there, schools and medical care facilities are scarce and most of the villagers have left for the cities in pursuit of a better life.

Word Press Photo prizewinner Danila Tkachenko (b. 1989) is known for his even more radical approach to this subject. He burned down an abandoned village in his most controversial project ‘Motherland’. This Neronic gesture generated some exceptional photographs as well as a lot of public outrage, presumably one of the artist’s main goals in the first place. The village was already condemned to oblivion, there is a sense that at least its passing was a spectacle worthy of attention.

The projects by both of these artists go far deeper than merely documenting the collapse of old wooden huts, devoid of modern comforts and hardly livable in by today’s standards. It is not just the traditional architecture, which is disintegrating in front of us, but the patriarchal, community-based way of life and frame of mind. Historically a peasant country, it was once prevalent in Russia and now is coming to an end. This way of life was first undermined by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and subsequent ‘collectivization’, then by Nikita Khruschev’s reforms that drew the population away from small villages to a few larger settlements, and finally by the collapse of the Soviet system and economic crisis of the 1990s. As it disappears completely, what will take the place of this death and decay?

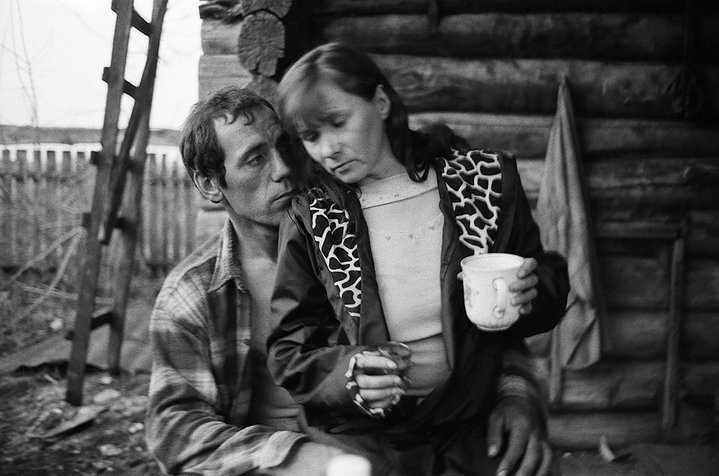

Alexandra Demenkova (b. 1980) from St. Petersburg turns her eyes and her camera lens to people rather than landscapes, and the results are not very reassuring either. She spends months in villages, immersing herself in the lifestyle of their inhabitants, whom she captures in black and white. She carries the torch of St. Petersburg’s Necro-Realists of the 1980s, a movement led by underground film director Evgeny Yufit (1961-2016) who was known for his macabre black-and-white imagery. Many celebrities of the city loved the exaggerated, carnivalesque aesthetics of his horror-packed fantasies and were keen to volunteer to star in his films. For Demenkova, even the simple, everyday routines of Russian villagers are an endless danse macabre. Movements are always frantic, faces are distorted by strong emotion (or chronic alcohol abuse), interiors are dilapidated and semi-dark, and even pets look like strange, hostile creatures ready to attack. In a life like that exaggeration is not necessary and hope is non-existent. Her dark, powerful aesthetics have brought Demenkova international recognition. Yet for the locals themselves, her vision is too accurate to please.

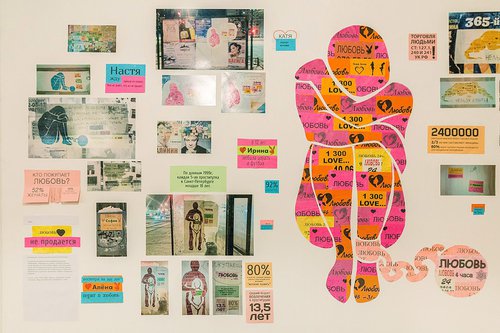

Artist Alisa Gorshenina (b. 1994), who goes by the name of Alice Hualice, a native of the small village in the Urals region, has one answer, although it is even more unsettling than the question itself. In her project ‘Russian Alien’ she manifests the intervention of eerie surreal entities (her own textile creations) into an otherwise peaceful, rural landscape. Crude hand-sewn masks that look like remnants of a grim shamanic cult and strangely clad female figures loom over the horizon or invade already abandoned houses. The artist poses in her own photos, styling herself as “a pagan goddess” as she puts it. When people leave and traditions shatter, chthonic, inhuman powers can take over.

Julia Kartoshkina. Hot off the Skillet

Museum of Russian Lubok and Naive

Moscow, Russia

January 2 – March 31, 2023