Recapturing Subjectivity: Gender in Contemporary Kazakh Art

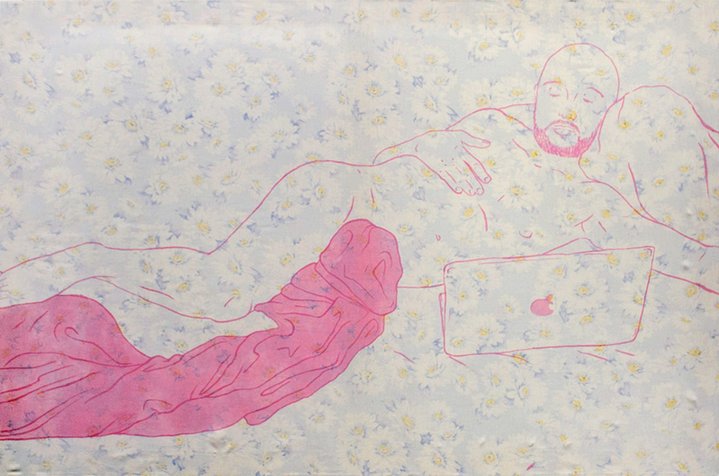

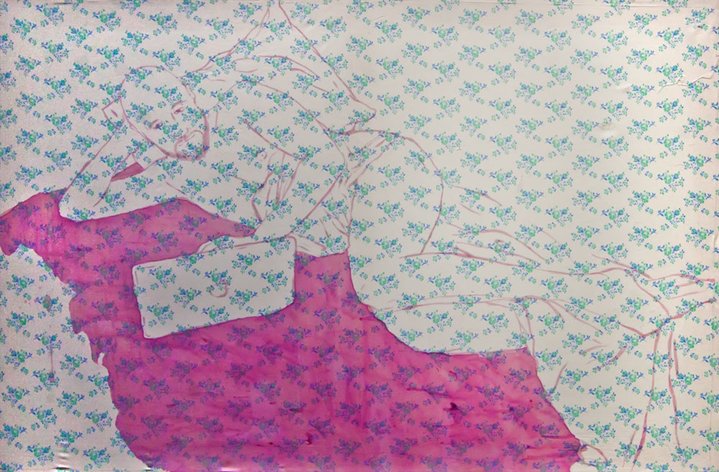

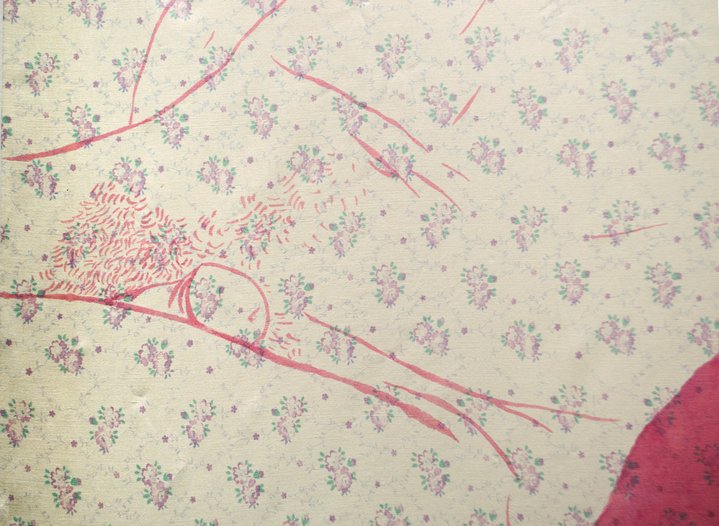

Madina Joldybekova. Mixed Feelings, 2021. Exhibition view. Dom36. Almaty, 2021. Courtesy of Dom36

Today gender issues are becoming manifest in the contemporary art of Kazakhstan where many women are now experiencing an identity crisis after centuries of unchallenged patriarchy.

In Kazakhstan domestic violence and sexual crimes are all too common yet the fear of public reprisals discourages many victims from coming forwards. In conservative families outside larger cities women are often still seen as voiceless and submissive wives, homekeepers and breeders. The post-colonial experience has now brought such problems of national identity into sharper focus. Women are often handed the gauntlet as guardians of tradition, unspoken standards to which they are expected to aspire. Today, against this background Kazakhstani women have become acutely aware of gender issues and they look for solutions.

Kazakh artist Aigerim Mazhitkhan's (b. 1986) installation ‘Beauties in Mourning’, first shown in 2019 at the landmark exhibition ‘Bad Jokes’ in Astana, is a moving statement about the all too common predicament of unwanted motherhood among young women in Kazhakh society. In this work the artist creates the illusion of a landfill where bins and bags overflow with what from a distance looks like rotten fruit yet go close and they contain stuffed fake breasts with pacifiers for nipples. This interweaving of the fate of mother and child implies a vicious circle of passing traumatic patterns down from one generation to the next. It references the many tragic cases of unwanted babies being discarded on rubbish dumps in Kazakhstan, yet on another level the title refers to a story by classic writer Mukhtar Auezov about a young widow whose rebellious body is taken hostage by traditional customs plunging her into years of mourning. Giving up unwanted babies can be seen as a desperate act of rebellion by a woman’s repressed subjectivity against her imposed social role. In Kazakhstan, single mothers are often still subject to social condemnation. In Mazhitkhan’s work, it is aggressive patriarchal models that are the object of her criticism. This work is a group portrait of women as objects, essentially breeding machines who have given away their youthful energies to perform what is seen widely as their maternal duty, and now they are no longer needed and are discarded.

The pacifier can be curiously seen as a knot, tying together the breast, which is like a ‘bag of stone’, a prison for repressed, undeveloped subjectivity. Zhanna Nugerbek (b. 1988) found a metaphor for this state at the exhibition ‘Ol kyz’ in Astana in 2022 where she presented a series of sculptures called ‘Women’. They are small cocoons made of soft foam rubber and fabric. The self of a woman, soft and submissive, repressed by her traditional upbringing, is imprisoned inside them.

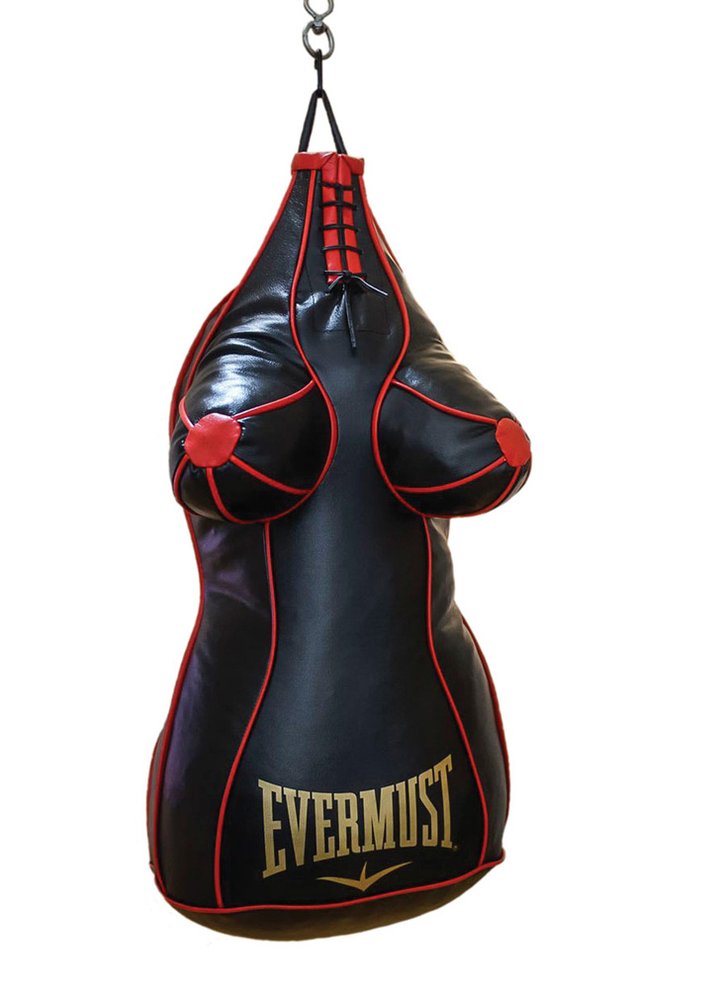

One of the manifestos of feminist art in Kazakhstan is ‘Evermust’ by Zoya Falkova (b. 1982), a piece which has been widely exhibited both in Kazakhstan and Europe. It is a punchbag in the form of a female torso; a portrait without a face. Associations with classical sculpture suggest the Venus of patriarchal society, a female deity stripped of her limbs so she couldn't fight back, her eyes so she wouldn't have her gaze and her mouth to be silent. The title of the work is a conceptual pun. Falkova associates the sports brand Everlast with the divine and traditional models of raising a boy and she turns this into ‘Evermust’ for women who in patriarchal families ‘always owe’ something to her husband. Like the woman-turned-chair heroine of Michel Gondry's episode from ‘Tokyo!’, the woman in the patriarchal family is gradually transformed into a punch bag, reduced to the purely utilitarian role of a weak-willed object, which also tragically allows her to be treated brutally. Yet here, there is a twist, unlike a real punch bag, the light weight of this work expresses feminine qualities of gentleness and vulnerability.

Criticizing the foundations of European patriarchal civilization, Falkova turns to antique black-figure vase painting. The vase ‘Her Own Guilt’ depicts the pursuit of a girl by male police officers who embody power. The title’s clichéd, cynical formula turns out to have been a constant fate over the centuries. Here on the vase this chase turns into what is a never-ending run around in circles. Traditional models dominant in society and passed down from generation to generation do not allow one to break free. The characters become prisoners of the chase, objects of tradition, like puppets or glove puppets moved by its invisible hands. In antique times, such vases filled with olive oil were handed out to the winners of competitions. For the heroine, the flight from repression also becomes a kind of competition, in which the prize is her recaptured subjectivity. But is it ever possible to win in an endless race around in circles?

In the series ‘#painting with borscht’, the artist herself plays out the role of a housewife-artist who is plagued by everyday worries and finds sanctury in her art. She uses sheets and duvet covers as her canvas, and borscht which the artist sees as a symbol of kitchen slavery replaces the traditional oil paints in works referncing classical art such as ‘Leda and the Swan’, ‘Venus before the Mirror’, ‘Olympia’. Here there is an institutional critique of art with the traditional distribution of gender roles. Falkova speaks of a ‘critique of the masculine viewer's gaze’, more accustomed to the depiction of the female nude. Here what seems to be important is a kind of recoding of roles with the housewife reclaiming her subjectivity through the process of the creative and reflective act.

One of the significant solo exhibitions of recent years was Madina Joldybekova's (b. 1991) ‘Mixed Feelings’, held in Almaty in 2021 dedicated to the theme of motherhood and its biased propaganda images. In Kazakh society, by imposing early motherhood people keep silent about the flip side. In a series of illustrations for a zine, the main theme is the merging of child and mother in the eyes of society. The image of the breast and its changes after childbirth become central in the rug series. The craft of carpet weaving traditionally associated with women's labour is a way to talk about female corporeality and personal experience. The artist juxtaposes the breast with dandelions, playing around with its ‘intoxicating’ milk, or with a chewed-up cassette tape, alluding to the tedium of breastfeeding, that gradually becomes a mechanical act. Thus Joldybekova also touches on the theme of estrangement of the breast, which it seems now belongs to the child rather than the mother. The triptych ‘Regular Star. Neutron Star. Black Hole’ deals with the transformation of the breast during the breastfeeding process and seeks to normalise it in society, as if to help women accept and assert themselves in this new round of life.

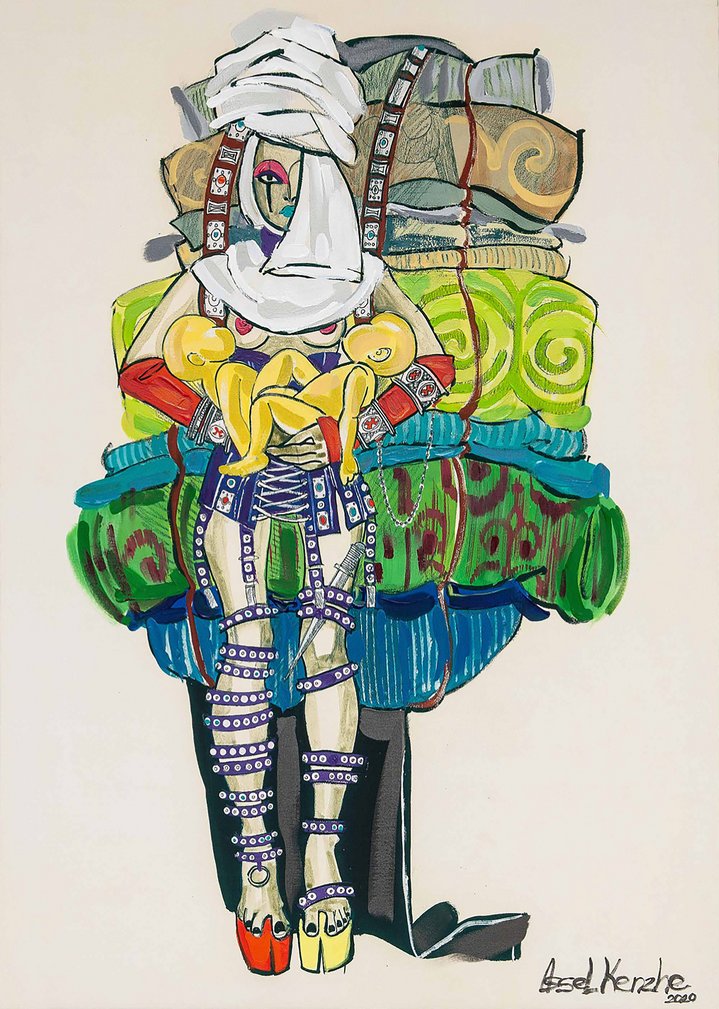

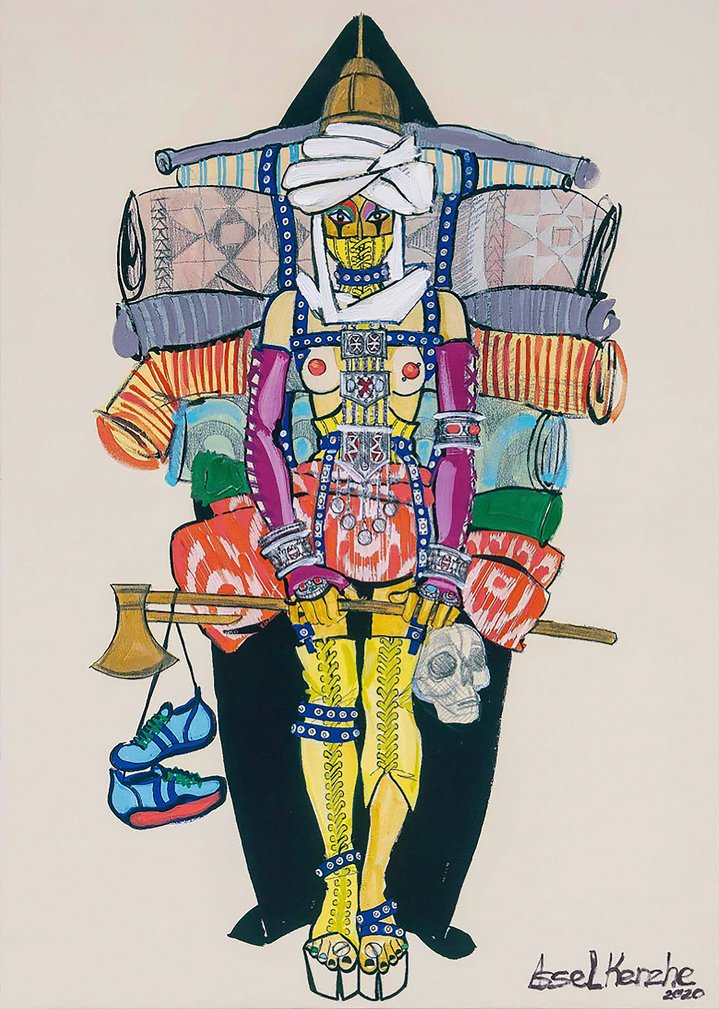

The series of works on paper called ‘The burning Kelin (zhasau)’ by Assel Kenzhetayeva (b. 1980) creates the polysemantic image of a Kazakh woman aged 30-50, to which society pays little attention. “There is always either a young girl or a wise old woman”, says the artist. “There's a gap between the two, and it is just seen as an age of becoming.” In this series Kenzhetaeva combines the style of glossy fashion magazines with Turkic traditions. Painted belts, bracelets and other national ornaments are made in such abundance that they seem to be a burden. Bracelets are reminiscent of shackles, and the mound of korpe (traditional blankets) in her hands or on her back evokes associations with a tortured pack animal. The artist shows us how women are constrained by conservative moral taboos and expectations of society, and finally, also how the overload with domestic work does not cancel out a woman’s duty to be seen as attractive by her husband. And then there are the trappings of a very different type: acid tights, highheeled shoes, the eroticism of the semi-naked body. There are sometimes weapons, knives on her belt, sometimes a sword or an axe suggesting that Kenzhetayeva's women are warriors and superheroines. In this context, the national tradition is fertile ground. "For me, it is important not only to show the 21st century woman, but also her free Turkic roots," says Kenzhetayeva, "Many Turkic women received a military education. Like the men, they took part in wars and campaigns. They played a very significant role in society.” This image of an independent and strong nomad woman is also traditional and could be a mainstay for a Kazakh woman today. The series does not only question the place of women in Kazakh society, but calls on her to understand herself and take her destiny in her own hands.

The art of Kazakhstan today that raises these thorny and enduring gender issues, in all its variety of media and individual themes, turns viewers to questions about human rights, the transformation of an outmoded hierarchical worldview, and the challenges of reclaiming subjectivity, the right of an individual to belong to him- or herself and to speak with one’s own individual voice. This problem is broader than just a gender agenda. The work and efforts needed to solve it are not only about self-realization and the building of horizontal forms of communication between people, but also engendering an environment of solidarity and empathy in Kazakh society. This means its ability to defend its rights and to develop.