Dmitri Lion: An Oeuvre Turned into a Holocaust Memorial

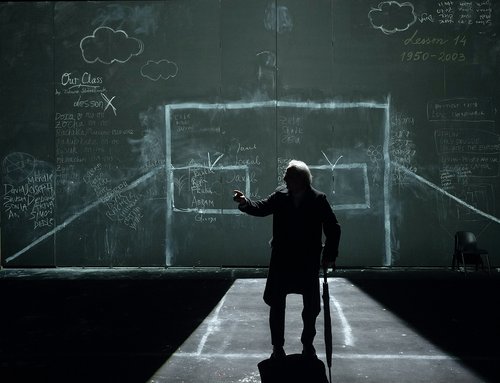

Dmitry Lion. Procession. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2026. Courtesy of Moscow Museum of Modern Art

At the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Dmitri Lion’s centenary exhibition brings his haunting Holocaust graphics back into view. Marching figures dissolve into strokes and stippled constellations, eroding the boundary between figuration and abstraction. The result is an imagery of witness – spare, relentless, and quietly devastating – descending into the darkest registers of suffering and grief.

This solo exhibition of Dmitri Lion (1925–1993), marking the centenary of his birth, has long been anticipated and carefully prepared. Its curator, Elena Kamenskaya, began developing the project in the 2010s, following the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts’ receipt in 2014 of a gift of eighty graphic sheets by the artist. Ultimately, the exhibition – intimate in scale yet considerable in weight – was organised in partnership with the Russian Jewish Congress and opened at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art as part of Moscow’s “Week of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holocaust” programme.

Lion occupies a distinctive position within the intertwined spheres of Soviet official and unofficial art. He supported himself largely as a private tutor, preparing schoolchildren for entry to the Polytechnic Institute, and was granted only one solo exhibition during his lifetime. In 1990, the Central House of Artists in Moscow presented “Procession,” accompanied by a modest catalogue featuring an introductory text by Yuri Molok and excerpts from the artist’s notebooks.

Lion was born in Kaluga, some 200 kilometres from Moscow, into a lawyer’s family. After graduating from Moscow Art School No. 1, he entered the graphics department of the Moscow Architectural Institute. A veteran of the Second World War, he spent ten years in the Soviet Far East and, after demobilisation, enrolled at the Moscow Polytechnic Institute in 1953. It was there that his language began to crystallise: the Holocaust as an unwavering subject, and a graphic vocabulary pared down to essentials. Lion himself could not pinpoint when he first learned of the Catastrophe – Soviet official ideology did not, as a rule, distinguish Jews from other wartime victims – yet the fact of it became a private, permanent metric. In Moscow he pinned a sheet above his bed with the number 6,351,000, written in his own hand: the count of Jews murdered by the Nazis.

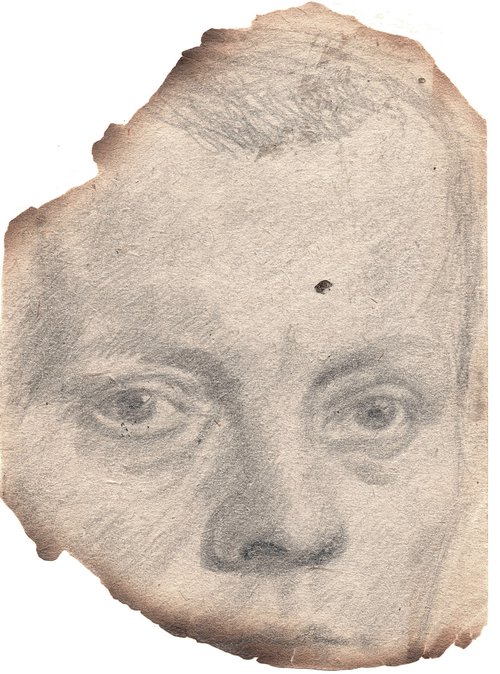

Dmitri Lion. Untitled, end of the 1950s. From the collection of the AZ Museum. Courtesy of AZ Museum

The exhibition ‘Procession’ begins with an introductory “informational” room: gates recalling Auschwitz, and a concise chronology of the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” from 1933 to 1943, compiled by historian Ilya Altman of Moscow’s Holocaust Centre. From there, the visitor is drawn into an installation-as-passage. Works on paper hang along a narrow, dark corridor-labyrinth devised by Dmitry Baryudin of the Architectural-Artistic Agency Poslezavtra. The works are deliberately heterogeneous – drawn from different series and holdings, including the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, the private Museum AZ and the Museum of Contemporary Art ART4, as well as private archives, among them the artist’s family. The staging makes the viewer, quite literally, a participant: one of the “walkers” within the procession. Lion, too, positioned himself among the survivors of the Catastrophe; after drawing fourteen sheets of “the walkers,” he named himself the fifteenth.

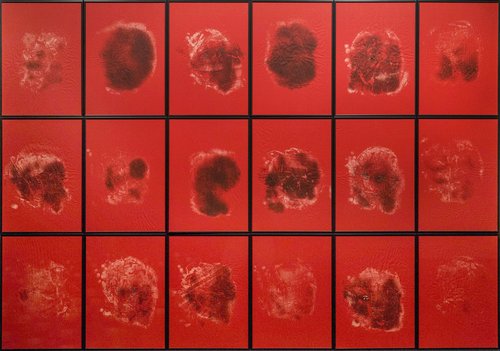

The overarching theme of the Holocaust – the disappearance and scattering of millions of people – is rendered in Dmitri Lion’s graphics with stark literalness. Figures dissolve, melting into constellations of strokes and dots, as if the human body were being erased before our eyes. This effect became the hallmark of Lion’s idiom. He worked at the threshold between figuration and abstraction, between legible mark and expressive flourish, between direct statement and metaphor. He never corrected a sheet – preferring to start anew if something misfired – worked with a reed stick and ink, and never pulled the pen backwards.

This method, thoroughly modernist in spirit, was also conditioned by the Aesopian language of late Soviet art, with its porous line between the permissible and the forbidden. Lion – a pupil of Ivan Chekmasov (1901–1961) and Pavel Zakharov (1902–1983) – deliberately turned away from the then-fashionable linocut manner associated with Vladimir Favorsky (1886–1964). Instead, he argued for easel drawing by hand, “without the destructive carpentry oversight of hatching”; and even in printed, ostensibly “mechanical” works – his nervous etchings – he sought to preserve the immediacy and volatility of ink, reproducing the spontaneity of a living stroke.

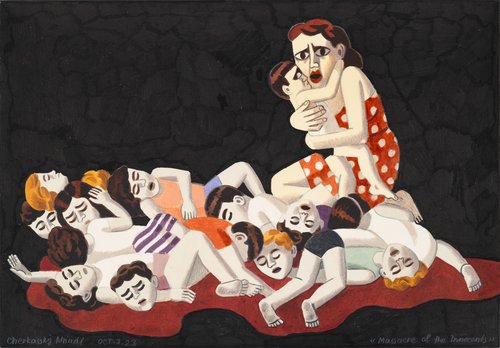

As for themes, the exhibition ‘Procession’ presents far more than processions alone. There is, for instance, the pen drawing ‘Male Portrait’ (1962), whose speckled, vibrating touch recalls Anatoly Zverev’s (1931–1986) “spotty” manner; and ‘Three Figures’ (late 1950s), a group of pregnant women rendered with severe economy. ‘Picture of the Yids’ (1959–early 1960s) is more grotesque and satirical: male torsos tattooed with Lenin–Stalin profiles are topped with Tishler-like ship-hats, a theatrical absurdity that sharpens rather than softens the work’s sting. From the artist’s family comes a sheet from Lion’s celebrated cycle ‘Fates of Russian Poets’ (early 1960s), where “executioners” in pseudo-historical costume urinate on severed heads – an image of humiliation as historical method. Nearby hangs ‘Three Lives of Rembrandt’, a revealing point of identification: for Lion, Rembrandt was something like an alter ego. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), who died in poverty and obscurity in the Jewish ghetto, drew and engraved with a radical freedom: biblical protagonists appear in fantastical dress, erotic subjects are unflinchingly direct, and the line alternates between long, fluent flourishes and abrupt, broken marks, leaving broad planes of the sheet untouched.

Lion, too, worked with that charged “white” space – what he called the “density of white.” He insisted that “lines are cracks, they both destroy and connect,” and that “in drawing there is no arbitrariness, but everything is arbitrary.” In other words: the mark is never innocent, yet it is never wholly governed – an ethics of line that runs through even his most sparing images.

The exhibition closes with something like a premiere: a vast sheet of ink populated by yet more walkers (‘Untitled’, 1970). As in much of Lion’s work, the figures advance from right to left, as if not moving forward but returning – drawn back through time rather than released into it. Within the dark current of marks, individual presences surface: male figures, a woman, a child, even a dog. With its cubified, somewhat naïve articulation, the drawing shifts Lion’s lineage. It no longer reads primarily as an inheritance from draughtsman predecessors – Rembrandt, Leonardo, Pushkin – but places him decisively among modernist contemporaries: Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Paul Klee (1879–1940), and Cy Twombly (1928–2011).

In a substantial 1996 article in ‘Questions of Art Studies’, Lola Kantor-Kazovsky situates Lion’s oeuvre against the aesthetic horizon of the Thaw – “the period of the greatest aesthetic upsurge in society” – and defines it as anti-aesthetic: drawing-as-script, smudges, crossings-out. The artist, acting more “unconsciously,” is cast as a “seismograph,” registering tremors that language and ideology could not openly name.

Yet in 2025–2026 – when Moscow is marking the centenaries of icons of Soviet non- and semi-official art with major exhibitions – Dmitry Krasnopevtsev (1925–1995), Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016), and Ernst Neizvestny (1925–2016) – Lion’s manner reads differently. What once appeared raw or anti-aesthetic now seems composed and intentional: built around through-plots, governed by clearly calibrated lines, and sustained by a disciplined graphic logic.

If one were to assemble a sequence of social metaphors in late Soviet “strange” art (to use the term of literary critic Alexei Konakov) – alongside Mikhail Roginsky’s (1931–2004) pink fence and red door, Krasnopevtsev’s broken jugs and “gallows,” Ilya Kabakov’s (1933–2023) public toilets – then Lion’s “processions” would stand among the most potent allegories. His biblical figures and imprisoned Jews can be read as a generalised image of a society in stasis: a collective movement that goes nowhere, a trudging persistence without horizon. Within that climate, artists of genuine talent – refusing state commissions, resisting prescribed themes and the predictable stylistic infrastructure that accompanied them – too often remained without broad recognition.