Boris Sveshnikov, the Mystic from the Gulag

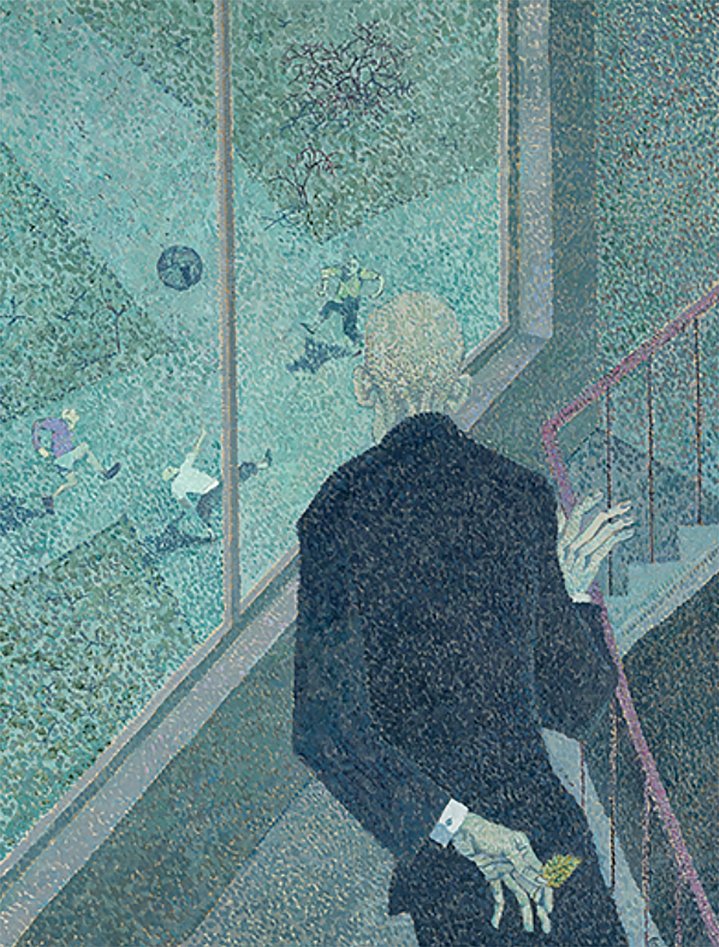

Boris Sveshnikov. Dusk Shadows, 1970. PROMETHEUS Art Foundation Collection. Image from Nashi Khudozhniki Gallery's website

A solo exhibition at Nashi Khudozhniki gallery in Moscow pays homage to an artist whose style does not fit into constraints of any art movement and who spent his formative years in Stalin’s labour camps.

A glow and a shimmer, vibrations and echoes which hum, an atomic swirling of coloured particles and sfumato, there characterise the style of early 20th century mystical painting and Boris Sveshnikov (1927–1998) was among a pleiad of artists who rediscovered its possibilities in their symbolist and metaphysical paintings. The Russian painters of the postwar generation, who had fallen by the wayside of official Soviet art, revived symbolism and post-impressionism with almost sacred, missionary zeal. Their art exists on a very thin, fragile line between Revelation and Eclecticism. They are both Blessed, and Spiritualists at the same time. Boris Sveshnikov, in my opinion, easily fits into the pleiad of such strange post-symbolists, alongside Vasily Sitnikov (1915–1987) and Alexander Kharitonov (b. 1931), both of whom also favourites of gallerist Natalia Kournikova, who founded Nashi Khudozhniki in 1995.

These three artists each found their own unique path in art, yet, as Mikhail Sokolov, a researcher who wrote a book about Kharitonov notes these three artists are all united by a religious-symbolist style. In the case of Sitnikov, it is mirage-like, in the case of Kharitonov and Sveshnikov, mosaic.

There is a remarkable article in the exhibition catalogue written by the late art historian Anna Chudetskaya, who was a major expert on works of art of the period of unofficial art. Her article details the creative biography of Boris Sveshnikov in the context of his personal human suffering. At the age of 19, in 1946, Boris Sveshnikov was sent to a labour camp by false accusation. Sveshnikov then spent eight years in the Gulag together with Lev Kropivnitsky (1922-1994), a fellow student at the Moscow Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts and later a well-known unofficial artist. Sveshnikov's camp drawings were called ‘visions of eternity’ by dissident writer Andrei Sinyavsky, a definition which gave the name to the exhibition at Nashi Khudozhnki. The artist thanked fate for his suffering. It directed him to full immersion in the creative process, without regard for surrounding mundane reality. Writing about our world, he said, “[it] is so vast and deep that in comparison all the hardships of reality seem to me insignificant and bearable...".

In the early 2000s, Igor Golomshtok, a researcher of totalitarian art, wrote an article about Sveshnikov's camp drawings. For the first time he outlined the extraordinary scale of the artist's creative activity in the extreme conditions of the Gulag: he made hundreds of drawings and dozens of paintings. Sveshnikov worked with an incredible intensity. He created everyday sketches, and grotesque fantastic subjects, and landscapes, and allegorical compositions. These allegorical compositions of his camp years are more often devoted to the threshold of death such as ‘Funeral of a Child’ or ‘Funeral of Don Juan’. Strangely, in his camp works the artist combines the lessons of Soviet realism with variations on the Renaissance, Baroque and Mannerist paintings he knew and loved. Sveshnikov showed himself to be a unique autodidact whose style does not fit into any canon or tradition. His work is reluctance to fit any comfortable definitions, there is an almost annoying simplicity and risky rapprochement with kitsch and salon that you also can see in the works of Pavel Tchelitchew (1898-1957), another favourite artist of the Nashi Khudozhniki gallery. Like Tchelitchew, Sveshnikov found himself close to the Russian version of surrealism.

After his return from the Gulag in 1954, Sveshnikov found himself back in the normal social mainstream. At first, he lived in Tarusa, a small town about 100 kilometres from Moscow which became a haven for underground artists. He became friends with the families of artist Eduard Steinberg (1937–2012) and writer Konstantin Paustovsky. Then he moved to Moscow where he joined the Moscow Union of Artists and worked as an illustrator at the ‘Khudozhestvennaya Literatura’ (‘Fiction’) publishing house. In his book illustrations you see a sophisticated, pen-and-ink sketchy style, whole drawings modelled with a single outline. Thus, he would create the effect of a fleeting vision. Blow a breath, and the picture would dissipate! His favourite authors whose books he illustrated were the romantics, from Goethe, Byron and Hoffman to Hans Christian Andersen and Jacob Wasserman.

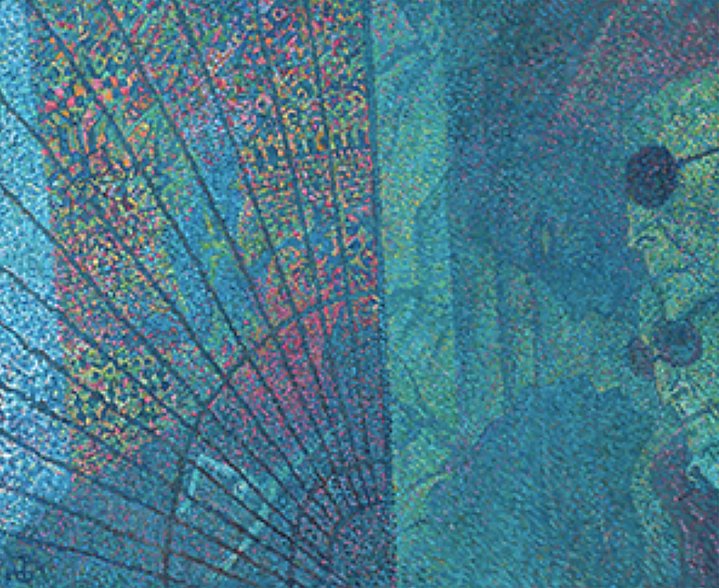

In his paintings Sveshnikov gradually moved towards his own version of post-symbolism. He rediscovered pointillism, a manner of painting with coloured dots. However, the purpose of this technique was radically different for him than that of the circle of Impressionists of Paul Signac (1863–1935). For Sveshnikov, it was not important to catch coloured air on the retina of the eye and enjoy a beautiful moment frozen in time. His dot technique is an atomic structure of the world, a giant stained-glass window that he assembled from nerve fibres and craquelures. For Sveshnikov it was important to see this essential atomic structure, the anatomy of the world, rather than to enjoy its lightness. This is why in his compositions of the 1970s and 1990s he is more an heir to the analytical school of Pavel Filonov (1883–1941).

Symbolism, Pointillism, or Filonov's studio, but in the end Sveshnikov did not identify with any artistic movement. He moved in his own system of strange associative hallucinatory convergences and associations, which are both universal and unreliable. They have an effect like a mirage. For example, in ‘Angel's Day’ from 1970, two elegant ladies sit at a table covered with a red tablecloth. On the tablecloth is a shot glass with berries. A frog is reaching for them. The background of the Mannerist composition are barracks in a snow-covered labour. Perhaps it is a view from the window? However, the cracks running right across the landscape make one think that the landscape is laid with ceramic tiles. Then the strange background with the snow-covered barracks risks absorbing the ladies at the red table into itself as well. Perhaps they too are part of a dreamlike illusion that has become an archetype of Sveshnikov's wounded memory.

Networks of capillary vessels, which create a similar effect to Tchelitchew's anatomical dissection of the world, cover Sveshnikov's late paintings with ever increasing insistence. The viewer's eye is constantly trapped: boxes of illusory worlds are opened, but the boundaries of their transition are elusive. In continuation of the philosophy of the metaphysicians and symbolists, death and the boundary between dream and reality become leitmotifs. For example, in the 1987 painting ‘Fallen Leaves’, Hoffmanian people wander along a boulevard. A cane pokes at a pile of colourful leaves. If you look closely, the leaves turn out to be skulls and bones made of coloured pieces of smalt. In his late work, Boris Sveshnikov opens up the shell of everyday things in order to find his way into the space that today is commonly referred to as either glitchy or virtual. The visionary anticipation of new thresholds of understanding the image was made possible by the fact that the artist created himself outside canons and dogmas.

Boris Sveshnikov. Visions of Eternity

Moscow, Russia

10 November 2023 – 28 January 2024