Major Ukrainian art Bequest Enters the Pompidou Centre

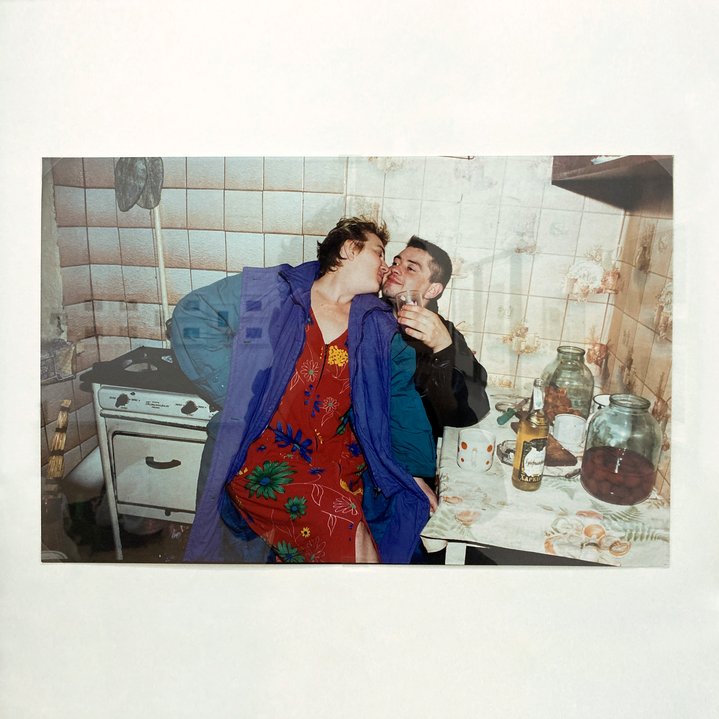

Boris Mikhailov. Untitled, 1975–1986. Gelatin silver print. Photo Karina Karaeva

Thanks to the ambitious efforts and enthusiasm of several artists and collectors, the Pompidou Centre has received a generous donation of Ukrainian art from the early 1960s till today. It is now on display as a part of the museum’s permanent exhibition.

A large cache of contemporary Ukrainian art, forming a single donation, is now on public view in Paris at the Pompidou Centre due to a heroic collective effort over several years. It was the brainchild of an international group of industry professionals, including Ukrainian curators Alisa Lozhkina, Oleksandr Solovyev, and Oksana Barshynova, deputy director of the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv. The bequest covers several key periods in the history of contemporary Ukrainian art from the 1960s onwards, finding points in common with both Russian and European art of the era. Chronologically, it begins with the works of Oleg Sokolov (1919–1990), a proponent of op-art and its subsequent spin-offs. A pleasing resonance is created between Sokolov’s aesthetics and the art of Giuseppe Penone (b. 1947) which at the Pompidou are displayed in the next room, both espousing anthroposophical notions.

Some might see this platform as a political intervention and the works themselves find an authentic, new voice in the disjointed narrative of today’s political context. How to articulate an artistic narrative fit for our complex world? In Janna Kadyrova's (b. 1981) ‘Second Hand’, photographs record objects extracted from the original narrative of the urban space; these works are not about reconstructing space, but a reflection on its destruction, a disturbance in the landscape. And the material Kadyrova works with, ceramic tiles, becomes a symbol of a place that has fallen into oblivion. Nikita Kadan's (b. 1982) sculpture ‘Pedestal. The Practice of Exclusion’ is altered from a monument of collective trauma into an object of violence against heroism, in which one waits for a hero.

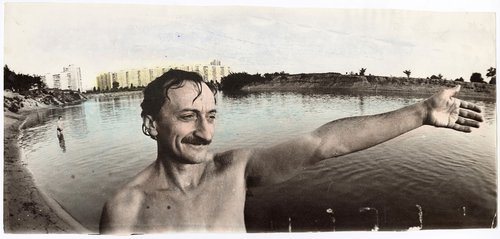

Serhii Solonsky (b. 1957)’s series of macabre photographs of the everyday life of his neighbours, places the era on a pedestal in a different way. It is an era in which disaster and salvation is concealed in the banality of everyday life. Roman Pyatkovka (b. 1955)’s photographs, in the best tradition of Dadaist art plays with the low life. Freedom symbolised in pornographic brutalism characterizes not only the spirit of the late eighties, but also the influence of Boris Mikhailov's (b. 1938) aesthetics to which Pyatkovka turned and which began to take on forms of alienation and defamiliarization.

The centre of the exhibition evokes Boris Mikhailov's works. There is the spirit of punk freedom in the actions of Vladimir Naumets from the series ‘A Sign on Snow’ (b. 1945), which continues the tradition of Moscow Conceptualist art group Collective Actions. In Juri Rupin (1946-2008)’s utopian photography he uses pointillism harking back to both the tradition of Rouault and Redon, in describing hell. The black and white aesthetic of Rupin's is evocative of absolute artistic freedom, the same freedom that is expressed in the period of refusal of the representatives of the ‘new wave’ REP grouping, for example, in ‘Atomic Love’, in which representatives of this wave Ilya Chichkan (b. 1967) and Pyotr Vyrzhikovsky mock the hedonistic ideology that characterized the Orange Revolution. People in silver protective suits, or spacesuits, make love in an industrial landscape.

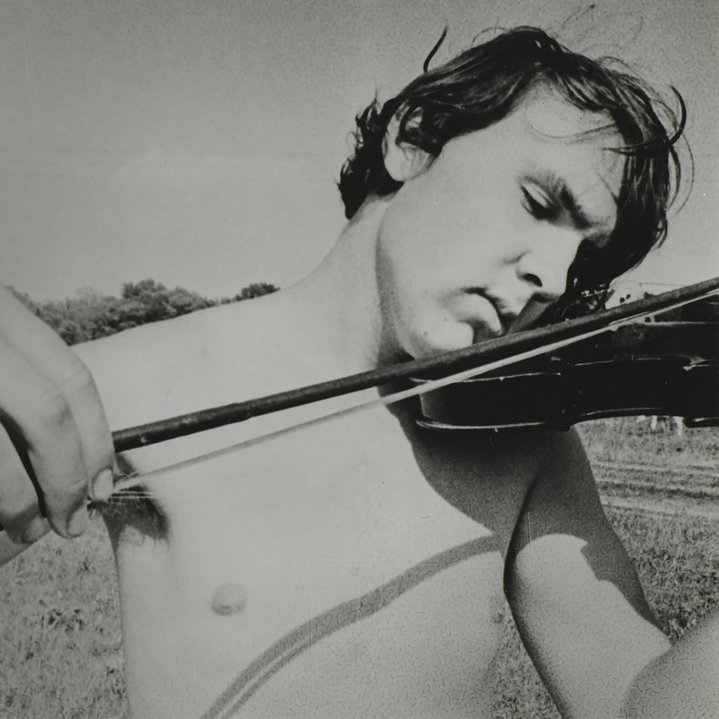

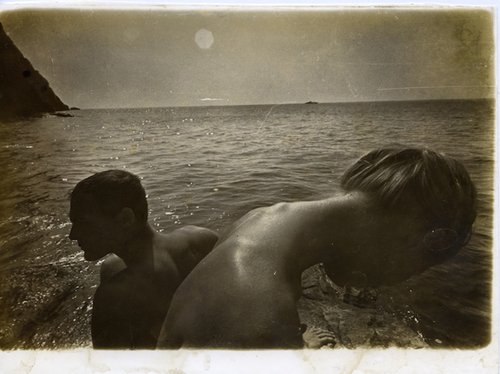

The older generation represented by Evgeniy Pavlov (b. 1949), whose photograph ‘Cello’ (1972) was published in Fotografia magazine in 1973, strikes similar notes. His work is part of a series of happenings, where young naked hippies acted as saboteurs against the KGB. By speaking out against the Soviet domination in the Ukraine and embracing pornography, Vremya (Time) group and the Kharkiv photography school opened up other vehicles of visual expression using collage, such as in Oleksandr Suprun's (b. 1945) works, which vulgarized and poetically defamiliarized the reality that replaced the Soviet aesthetic with the new revolutionary one. Finally, this new aesthetic is splashed out in a series of photographic works such as documentation of an action of the Shilo group (Vladislav Krasnoshchek (b. 1980), Serhiy Lebedinsky (b. 1982), Vadim Trikoz (b. 1984)), in which the heroine of the Orange Revolution Yulia Timoschenko makes a night-time escape. She stops at flats of women of easy virtue, captures on camera what's going on, accidentally gets spotted sitting on a bench with a passerby, and finally throws off her mask. This intrinsically mad and desperate act is presented by the Shilo group as something subversive, which both poeticises the language of the new experience and becomes an attempt at a political statement.

The exhibition closes with works about utopian spaces and thought, nurtured by naive perceptions. Fyodor Tetyanich's (1942–2007) paintings are marked by a critique of the space of the cosmic future, of a new anthroposophical universe in which man is pure and innocent and in his non-normative behaviour he resists the Soviet legacy of the suppression of the individual, a condemnation of strangeness, but Tetyanich opens up the perspective of collage thinking, of a genuine revolutionary spirit, which a little later takes shape in the expressive, politically engaged works of Oleg Sokolov, Leonid Voitsekhov, and Sergei Anufriev (b. 1964), also on view at the exhibition.