White Gold Painted for the Revolution

To Save the Revolution To Help the Famine Victims. Porcelain platter by The Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg, period of Alexander III, 1893, and The State Porcelain Factory, Petrograd, 1921. Courtesy of Christie's

Why should the Russian Revolution and the Russian artistic avant-garde be seen as almost synonymous? Reflecting on the current exhibition of Soviet Revolutionary porcelain at St. Petersburg’s K-Gallery, art critic Pavel Gerasimenko wants this widely accepted conceptual unity to be treated with new critical approaches.

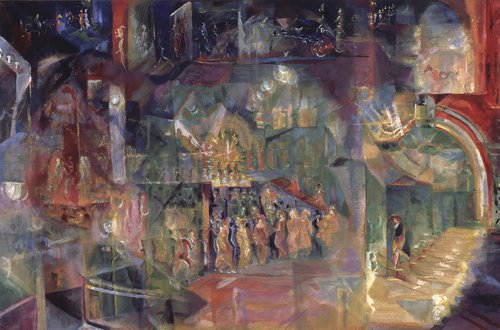

Paintings by Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) like his iconic ´Red Cavalry´, have long adorned the covers of countless books about the revolution, and the political dimension of this art has always been obvious. The advocates of left-wing art were aligned with Russia´s revolutionaries from the very beginning as they had a common goal: to break the old order whether in aesthetics or politics. In the Soviet Union from the 1960s to 80s, this association between art and the revolution was seen positively and from it emerged the first avant-garde art shows such as Russian Futurist exhibitions at the Moscow Mayakovsky Museum.

Fast forward to the present. Over the past year, several exhibitions in St. Petersburg have placed a special emphasis on Soviet porcelain. At the Hermitage there was ‘Russian Avant-Garde. The Revolution in Art’; at the Russian Museum retrospectives of Malevich's students and artists in his circle, including Anna Leporskaya (1900–1982), Nikolai Suetin (1897–1954) and Ilya Chashnik (1902–1929), all of whom worked at the Leningrad State Porcelain Factory; and, finally at K Gallery, ‘Born of the Revolution. Masterpieces of Propaganda Porcelain from Private Collections’.

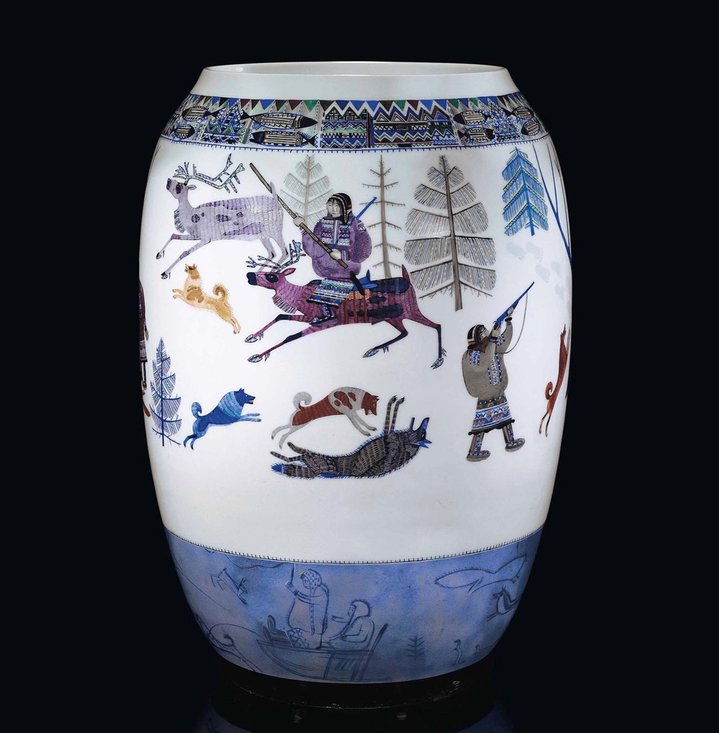

Collecting porcelain is a very well-established field, but Soviet-era pieces only attracted collectors over recent decades, and this resulted in a boom (until the current hiatus which have seen Russian auctions cancelled) with pieces from the 1920s and 30s being sold for record prices at prominent Russian auctions at Sotheby's and Christie's. In the last decade there have been exceptional results achieved for Soviet porcelain. In January 2013 at Christie's, a large vase with Eskimo hunting scenes painted by artist Ivan Riznich (1908–1998) sold for £422,500 against a pre-sale estimate of £30,000-50,000; in November 2020 at Christie's a platter 'Save the Revolution, Help the Hungry' painted by Ekaterina Yakimovskaya (1895–1970) from a sketch by Rudolf Vilde sold for £275,000 against pre-sale estimates of £20,000-30,000. At the last dedicated Russian auction held by Sotheby's in November 2021, a vase from the Leningrad Porcelain Factory sold for double the estimate showing demand was still high. Even in 1932, on the eve of the birth of Socialist Realism, which spelled the end of artistic freedom in the USSR, the applied arts remained relatively independent. In this piece, bought in the Sotheby’s auction and currently on display at K Gallery, figures of circus artists are painted in the spirit of international Art Deco.

Pyotr Aven is one of the most important collectors of Soviet porcelain. Back in 2014, in an interview with The Art Newspaper Russia, timed to coincide with the release of a three-volume catalogue of his porcelain collection, Aven revealed the true extent of his collection: with 1,500 museum-quality pieces it is even comparable in size to the holdings in the State Hermitage Museum. Today almost all the porcelain he owns is stored under lock and key at his estate in the UK as after the Russian-Ukraine conflict began, most of Aven's assets were blocked by court order. A niche part of his porcelain collection was made in Latvia in the 1920s and '30s exhibited at the Riga Porcelain Museum in 2015. More recently, a similar exhibition planned in another Latvian museum in February 2022 was cancelled upon the insistence of the country's Foreign Ministr, seen by many as a controversial move.

The Avant-garde was one of the Soviet Union’s, and later Russia’s, most successful cultural exports. There was the famous exhibition ‘Moscow-Paris 1900-1930’ held at both the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1979. In 2005, the exhibition ‘Russia!’ at the Guggenheim in New York ended with Malevich's ‘Black Square’. In 2008, the Russian Avant-Garde was legalised as a national treasure during the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics in Sochi. Since the beginning of the armed conflict with Ukraine, international cultural ties have been severed and Russian museums can now only fall back on their own collections for exhibition programming.

The idea of an inseparable link between the Russian Avant-Garde and the Socialist Revolution in Russia has long been widespread among both experts and the public at large. However, in 1917 in Russia there was not only a power takeover by the Bolsheviks that Autumn – in February of that year there was a democratic revolution which established the basic republican freedoms. And by this time this new avant-garde art had existed in Russia for near on a decade and had had time to develop authentically as a free artistic phenomenon before the Bolsheviks came along and gave the artists opportunities to bring their ideas to reality, something unprecedented in history.

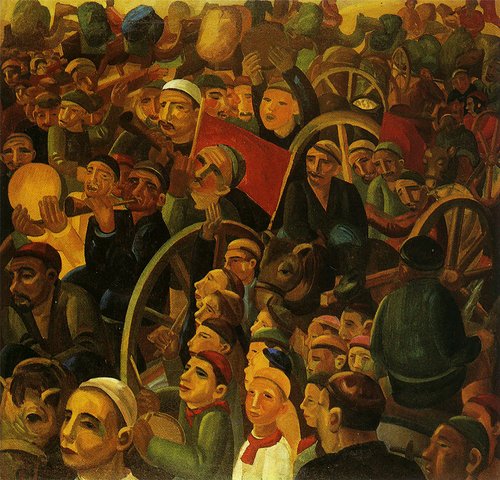

To mark the centenary of the Russian Revolution in 2017, exhibitions were held in London and New York., There was ´Revolution: Russian Art 1917 – 1932´ at the Royal Academy, curated by the research team at the Courtauld Institute under Natalia Murray, a scholar of the legacy of Nikolai Punin, and in New York, ´Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde´ on the rich material from the MoMA collection. Perhaps it was for marketing reasons that the word ´revolution´ in the titles of these two projects was directly connected to the ´Avant-Garde´. The Hermitage in St. Petersburg was more direct in its approach. An exhibition called ´Russian Avant-Garde: The Revolution in Art´ had been open for only one month at its outpost in Amsterdam, before it was urgently brought back to Russia in March 2022 and subsequently opened in St. Petersburg later that year, rebranded as ´Art for a New World´. Porcelain statues of both Emperor Nicholas II and Lenin greeted the viewer at the entrance on identical red backgrounds. For the last thirty years after the fall of the USSR, post-Soviet Russia tried to reconcile facts from its history by creating a curious hybrid that included both the monarchy and the Bolsheviks at the same time. After February 2022, this suddenly seemed unviable. The process of reverse dissociation of concepts might begin with art, and Russia may later find it hard to claim its revolutionary history.

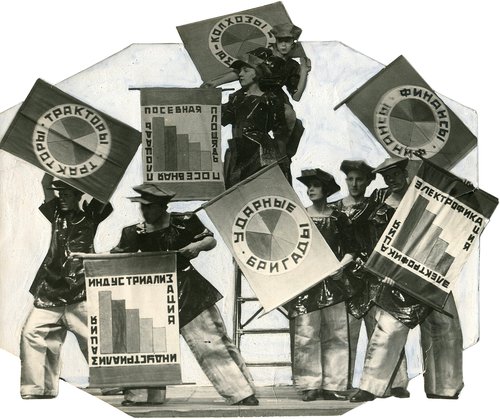

The love affair between the Avant-Garde artists and the Bolshevik authorities did not last long: it was over as early as 1921. Andrei Krusanov, who researches the Russian avant-garde, summarizes the beginning of the end: "We must admit that the policy of 'democratizing art' was highly effective in winning the sympathy of ordinary people and a significant part of the artistic intelligentsia. This policy was undoubtedly one of the tools which ensured the eventual victory of the Bolsheviks in the Civil War. While the leftwing artists of the time in question were sincere supporters of this policy, and had formulated its main provisions in the spring of 1917, before the Bolsheviks came to power, the Bolshevik government viewed the same policy in a rather utilitarian way, as one of the instruments of controlling the masses. After the victory in the Civil War, the very costly policy of 'democratizing art' was immediately reversed. The ruling party demanded that the arts perform purely utilitarian tasks: to educate, agitate, and propagandize in a communist spirit. The agitation-propaganda left art ran into a mass incomprehension".

Porcelain made in the first years of Soviet power, termed ´agitfarfor´, can serve as an example of the Marxist dialecticism of form and content. A large number of porcelain blanks, blank models, remaining at the Imperial Porcelain Factory renamed Leningrad Porcelain Factory after the revolution, were subsequently decorated by the Avant-gardists in the 1920s according to their own designs. These pieces were not for everyday use, in fact, much of it was exported as it fulfilled its propaganda mission beyond the borders of the USSR. This is one reason why an ‘agitfarfor’ show looks a bit like an antique shop window and thus why one is increasingly tempted to separate the notions of ‘Avant-Garde’ and ‘revolution’, which are in dangerously semantic proximity. One must draw a line between Malevich's dinnerware sets or Suetin's porcelain painting sketches from 1923 and the much more traditional figurines by Natalia Danko (1892–1942) from the early 1930s, whose characteristic types are even evocative of figurines made for the 300th anniversary of the House of Romanov, the ‘Peoples of Russia’ series. It would allow us to appreciate the revolutionary character of the truly innovative works and better understand the political meanings they contain. The true relationship between left-wing artists and left-wing politicians is confined to a brief five-year period between 1917 and 1922, after which time purely formal art was adapted to practical needs and occupied a local artistic niche. And the end of the avant-garde in Russia, and the transition of art to its new role, is indirectly evidenced by the exodus of convinced ideological avant-gardists into the applied arts, such as porcelain.

Born by the Revolution. Masterpieces of Propaganda Porcelain from Private Collections

St. Petersburg, Russia

13 April – 4 June, 2023