For the Preservation of Memory: Andrzhievskaia and Perm-36

An exhibition of works by Russian artist Anna Andrzhievskaia, dedicated to labour camp Perm-36, is now on view at the Gulag History Museum in Moscow. In this project, the artist addresses the sensitive issues of collective trauma and wilful oblivion in an indirect, yet personal way.

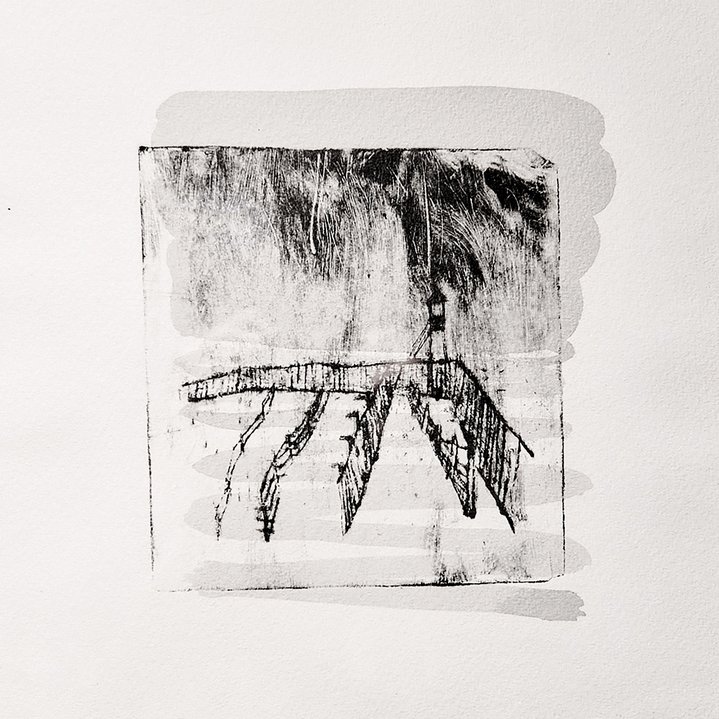

Small, black-and-white prints depict the depressing, ominous landscape of a labour camp. There are no people in sight, yet, oddly, the space does not look abandoned. A watchtower, a canteen, a penal cell, a barrack and other buildings from the camp infrastructure acquire a character of their own. Silent and forgotten witnesses of the past, they look ready to resurrect in the future. The exhibition setting, designed by architect Dmitry Markushev for the show at PERMM museum and re-created in Moscow, only adds to the claustrophobic atmosphere. Viewers have to enter a labyrinth of cramped compartments where they come face-to-face with these prints. Space and time are condensed and you cannot even look away.

Anna Andrzhievskaia was born in 1989 in the city of Perm in the Urals region although for many years now she has been a part of the St. Petersburg art scene. She studied monumental and decorative art at the city’s State Academy of Art and Design and attended an art school promoting contemporary art launched by ProArte Foundation. Upon graduation, she joined the North-7 group of artists who all shared the same studio and launched their own gallery where they staged exhibitions and performances. The leader of the group was Alexander Tsikarishvilli (b. 1983), a fellow student at ProArte. A few other well-known St.Petersburg artists, including Nestor Engelke (b. 1983) and Leonid Tskhe (b. 1983) were also members of the collective. “We were just a bunch of young art school graduates and nobody wanted to show our work. So we had to do everything ourselves”, she tells me over Zoom from her studio in Barcelona. Their space quickly became one of the city’s artsy hotspots and crucially the artists connected directly with curators, collectors and dealers in both St.Petersburg in Moscow, side-stepping the filter of local institutions and galleries. At that time Andrzhievskaia was creating wine fountains and doing performances that involved cooking and the consumption of food. “Now each of us is building a successful solo career, so we don’t do any joint projects anymore”, says Andrzhievskaia who moved to Spain a year ago. Here, she creates objects, graphic works and brightly coloured paintings with a surreal twist, populated with strange creatures and murderous plants.

Although her art is cosmopolitan, her early ‘Fencing System’ project focused on the history of her hometown of Perm and the darkest page of its history. Perm-36 was a labour camp a hundred kilometres away from the city. “It is a unique place”, the artist says, “it’s the only Gulag that remained completely intact, although many of them were still functioning until the collapse of the Soviet Union and there were still prisoners in some of them even in the late 1980s!” A lot of famous political prisoners were kept at Perm-36 including civil rights activists Natan Sharansky (who later became a deputy prime minister of Israel) and Sergey Kovalev, and dissident Russian Orthodox priest Gleb Yakunin. After the end of the Communist regime, the camp was turned into a museum. It opened to the public in 1996. In the 2000s, a political and cultural forum called Pilorama was held there every summer. Andrzhievskaia who was an undergraduate student back then used to attend it when she came home from St. Petersburg for the summer vacation. “There were public talks, concerts and film screenings, so for me, it was more like a festival”, she says. Yet she was intrigued by the history of the plays. “It struck me that the inmates had almost no personal belongings, not even the simplest most basic of things. No trace and no material, historical evidence was left.”, she says. They could spend fifteen years there, the only thing left behind being their personal file with a small photo. “Almost without exception, in the museum collection the only things connected to the inmates were battered shoes and boots, a huge mound of them. Clothes and fabrics disintegrated quickly, it was only the footwear which remained”. She felt the urge to make a piece of art about the place, although at that point she had no idea what exactly it would be.

Andrzhievskaia got in touch with the then museum director Tatiana Kursina who invited her to come and stay in the camp to work on her project. “One of the former prisoners’ barracks was turned into a hotel for researchers. I was allowed to stay there for a week.” She made a series of sketches and later turned them into prints during a workshop organised by St. Petersburg artist Alexandra Gart (b. 1988). Andrzhievskaia decided to make a series of edition prints based on her camp drawings. “The medium corresponded very well with my idea of the project,” she says. “The camp was called Perm-36, which means that there was Perm-35 nearby, and maybe Perm-37, too. An endless row of numbers, of buildings, a whole enormous machine of oppression.” And the print edition was based on replication as well. The series, printed in an edition of 10, was shown at several venues in St. Petersburg and Perm and finally made its way to Moscow this June. Currently, nine copies are in the PERMM museum collection and the tenth one is in the collection of St.Petersburg’s Museum of Political History of Russia. Perm-36 which started as an independent non-profit, was taken over by the authorities and became a state museum in 2013. Its funding was cut down and its founding directors Viktor Shmyrov and Tatiana Kursina were fired. The Pilorama forum also ceased to exist. Andrzhievskaia herself moved on to other projects and finally to another country. Yet, she thinks that it’s important to show this series in Moscow today.

“Nowadays, many people feel nostalgia for the Soviet Union. It seems to them that the final years of its existence were on the whole peaceful and harmless. They know about the repressions of 1937 or the early 1950s but they don’t realise there were political prisoners at Perm-36 even in the late 1980s”, she says. One can’t help feeling that there are a lot of stories and narratives from the past that have almost disappeared from the public discourse in today’s Russia. “There were a lot of people from different Soviet republics who were sent to Perm-36 for trying to save their language and culture. For instance, Ukrainian poet Vasil Stus died in this camp. Of course, I see a lot of parallels with the present day. And I see a lot of attempts to erase this memory”. For Andrzhievskaia there’s also a personal dimension to this story. Both her maternal grandfather and paternal great-grandfather passed through the camps in Kolyma. They both survived yet their experience was hardly ever discussed among their relatives. “The topic was immediately swept under the carpet in our family”, Andrzhievskaia says. She admits, that although her artworks depict camp buildings, that might soon disappear, her real goal was different. “The thing that I am interested in is the disappearing of memory, the hushing up of history. I wanted to show that it exists and it affects almost every family, every person – the memories may be erased, but the things that happened remain, nevertheless.”