Yuri Traisman: reconciling the irreconcilable

Today Russian art and culture needs passionate advocates more than ever before. With his foot in both North America his adopted home and Russia, collector Yuri Traisman has been promoting Russian Non-Conformist art around the world for over two decades and has no plans to stop.

Soviet Non-conformist art has grown in value over the past decade, with an infrastructure of galleries and dealers in the field, and increasingly stable auction prices in London and Moscow have supported it. Today Russia’s severed relationship with the West together with an increasingly hardline conservativism in the arts at home and new levels of censorship, will inevitably sow the seeds of a new generation of Russian dissident artists both within and outside the country.

It is a situation that has been before, which seasoned collector Yuri Traisman knows only too well. He began collecting underground Russian art even before the fresh winds of perestroika gathered across the land and led to the tentative opening up of Russia to the West in the early 1990s.

It was the generation which followed him, those who made great wealth during the years of privatisation in the 1990s who were part of the renaissance in Russian collecting we think of mostly today. During the late 1980s Traisman found himself collecting alongside the legendary Norton Dodge, competing for works, although they had different goals: Dodge was looking for artists who came from both within Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union. What interested Traisman most was Moscow conceptualism and the non-conformists associated with or living close to Moscow. ‘Sometimes we were offered the same art pieces, overall, the principal artists in both his collection and mine are the same’ reflected Traisman recalling the sometimes intense competition to acquire good works when they were both bidding for the same painting.

Despite this strict criterion, Traisman’s collection still has a curious eclecticism. At his stylish new home in Florida in a gated community with a picture-perfect lake just over the back garden (replete with swimming pool) he shows me a large porcelain vase with striking Soviet heroic imagery, from a collection he assembled of Soviet Revolutionary porcelain, much of which he has sold. He recalls the first time he encountered a piece of Soviet porcelain in the house of an art collector to whom he was introduced by Alexander Borovsky. He remembers his sense of awe at its wholesome beauty and it sparked off a collection he said eventually numbered into the few thousands. Although the earlier pieces created just after the Revolution were authentic artistic expressions of unsullied idealism, many pieces were created long into the late Soviet era when the slogans and images were eventually a tired form of propaganda. These works are politically at odds with the non-conformist paintings on his walls. Somehow he has managed to reconcile the irreconcilable, it is undeniably an incongruous vision. Yet Traisman was among one of the first collectors to understand the aesthetical and historical value of Soviet revolutionary porcelain, long before it became fashionable and highly collectible, fetching sums in the hundreds of thousands at auction in London.

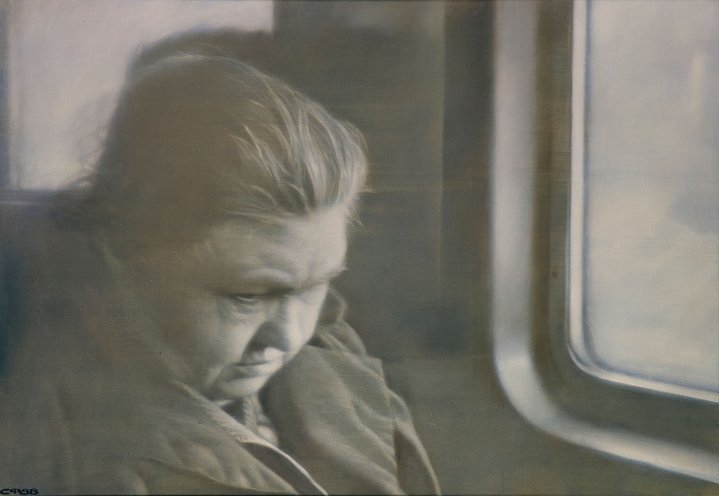

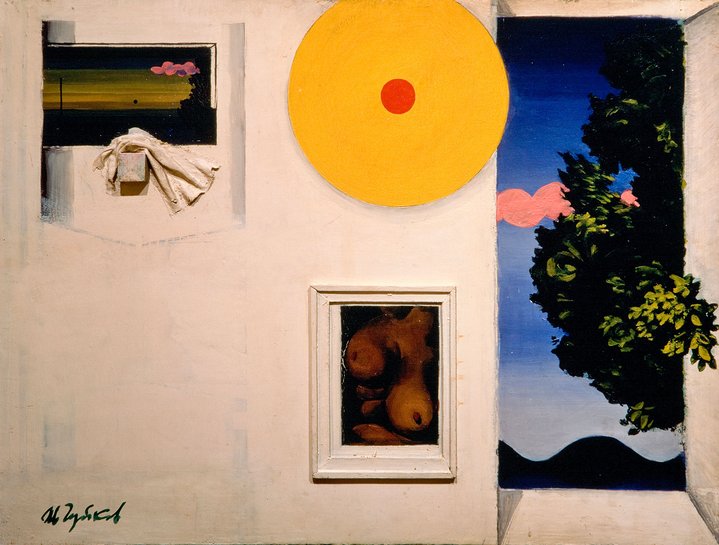

The Traismans moved recently from Greenwich, Connecticut, to the sunnier shores of Florida where there is no winter, like many Americans craving a better lifestyle after the miserable years of the pandemic. The usual challenges for an art collector to find the right house with the ceiling height needed for big paintings, made the search more complicated, but they eventually found their new home. Despite the big change, they kept some familiarity, the house stylistically reminds me of their old place, formal, elegant and bright. Here I come across another touch of incongruity: the light palatial living room is dominated by an impressive yet dark, and slightly monstrous canvas by Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021). He was, it turns out, a personal friend. Traisman enjoyed the cameraderie and friendships with many artists, especially those who came to the US before and after perestroika, such as Ernst Neizvestny (1925–2016), Grisha Bruskin (b. 1945), Leonid Purygin (1951–1995) and others. Those that settled in New York did so after they had already established their careers in the Soviet Union. At this time, Traisman was collecting at a pace, boosted by the love affair the West had for Russia throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, ‘Ode to Joy’ and ‘Forbidden Art’ were exhibitions of art entirely drawn from his collection which toured around both North America and Russia during those decades. A one-man-band, he amazingly financed it all down to the smallest details, paying architects and translators, scholars and transport companies and crucially his singular vision was behind the shows.

I often wonder how prices were established for non-conformist art in the days when it was not sold at auction and there were no public results with which to determine value. It seemed a bottle of wine, or two, were useful. They slowed down negotiations, watered down the egos, although the artist often got the upper hand. Traisman recalls one time when he was visiting Oleg Tselkov in his home in Paris. After having several bottles of wine and ‘pelmeni’ made by his wife and mother-in-law, they got down to the business of negotiating the price of paintings. ‘It went like this: we would sit and look at the painting I liked and I would ask him how much he wanted for the piece. He then said, "the canvas costs $250; the paint costs $300; the stretcher costs $200." Then he would pause and from that starting point we would negotiate further until both of us agreed on the price … over another bottle of wine. As a result, I paid tens of thousands of dollars for his paintings.’

Yuri Traisman’s efforts to popularise Russian non-conformist art throughout North America and in tandem also among new collectors in Russia during the 2000s are tangible and he has no plans to stop. It is timely. The ‘cancel culture’ movement against Russian art has been uncompromising around the world since Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, even those openly against the invasion are finding themselves a target in the West. One day, cultural advocates like Traisman, who lived through the Soviet Union, experienced its last days, the resulting honeymoon period and falling out between Russia and the West and the stark new reality today, will hopefully play a part in ensuring support and visibility for those Russian artists who were or are today rejected at home and for the moment at least finding few willing audiences abroad.