Yuri darling: all you need is to live a bit

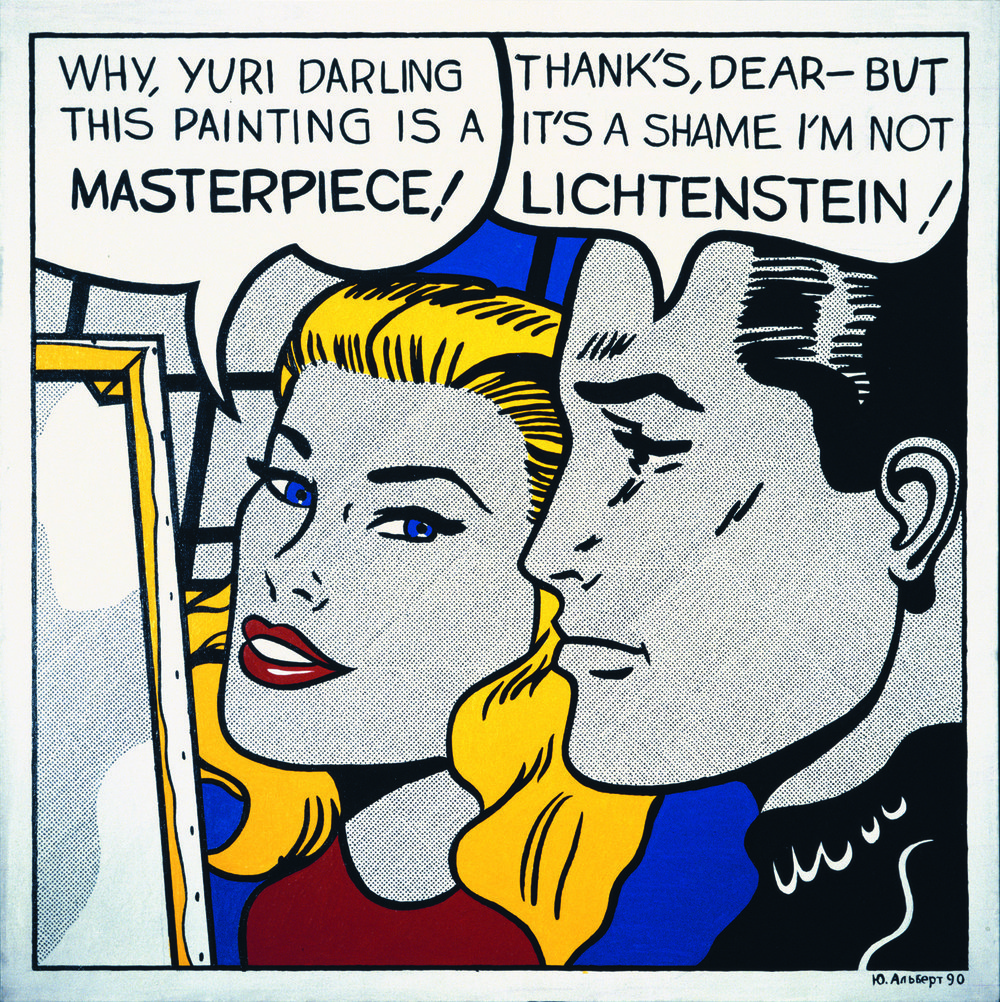

Yuri Albert. I am not Lichtenstein! 1990. Acrylic on canvas, 140x140 cm. Private collection, France. Courtesy of the artist

Yuri Albert explains life as lucidly as any artist since Warhol. Londoner Alistair Hicks argues that it is time to give him more credit.

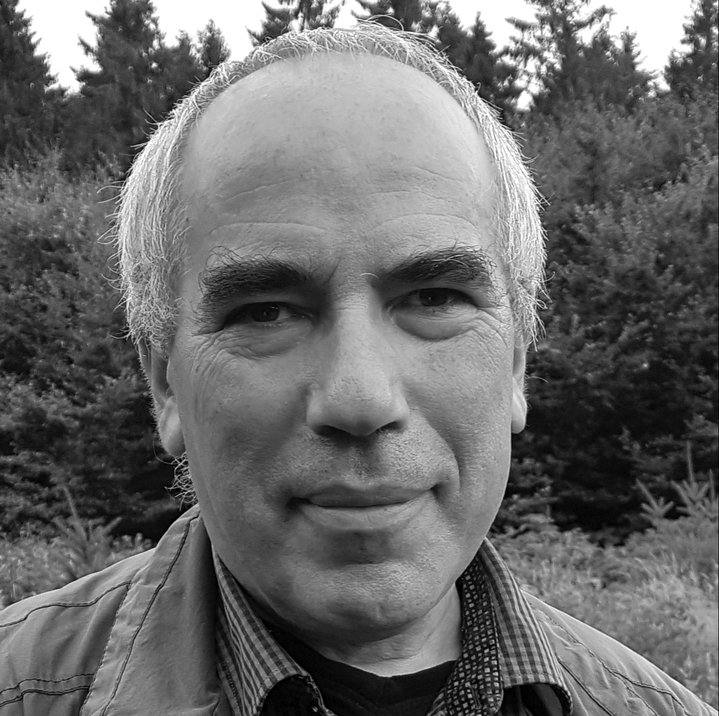

Yuri Albert (b. 1959) is a monster of our making, and, like Viktor Frankenstein’s creation, he feels unloved by us. Or at least, he does, if you believe his series, ‘Why they don’t love me’, 2007, or the words in his painting, ‘I am not Lichtenstein’, 2000. A blonde girl with the reddest of lips purrs: “WHY YURI DARLING THIS PAINTING IS A MASTERPIECE.” The superhero painter, replies, looking straight ahead with his jaw sticking out: “THANKS, DEAR – BUT IT’S A SHAME I’M NOT LICHTENSTEIN.”

He may be unloved, but as Yuri Albert was created by us and he puts up the mirror to our times as brilliantly as anyone. What is surprising, is that even for a foreigner like me, he is remarkably easy to understand. Well, let’s rephrase that. He is accessible even as he questions everything, because don’t we all? He is a great communicator, but he shares, if not leads, our scepticism about communication. He is not Roy Lichtenstein or any of those world famous Pop artists; he has also made ‘I am not Andy Warhol’, 1990, and ‘I am not Jasper Johns’, 1980. He understands the success of the New York/London Pop Movement expressed so neatly by British Pop legend Patrick Caulfield: “In advertising, you have to project or you don’t make a sale.” Of course, in 1980, when he started this series, it was almost impossible for unofficial Soviet artists to sell.

Do you remember the days when projecting yourself forward at the expense of others used to be considered anti-social? Yuri Albert does, though his family life is hardly straightforward. His grandmother was born in 1903 in the slums of London’s East-End. Her family were in exile from Imperial Russia, but when the regime was overthrown, she came to Moscow. She was literally at the heart of the Bolshevik Revolution. In 1920, that teenage ancestor even lived in Lenin’s Moscow house for two weeks.

Around the world, serious thinking has gone under the radar. The Moscow Conceptualists were among the first to react to this. In a world where people don’t trust words and images, those artists created a language out of the friction between the two. Albert’s frustration with words has been clear since his ‘I hope, this work with text will be the last one’ 02.1987. In Albert’s lament, ‘Why they don’t love me’ (2007), he set up a news ticker with comments from critics, artists, and curators. They write, “what exactly they don’t like about my work. Now try to imagine the artist Yuri Albert, based on all these rather contradictory statements.” The artist is putting the onus on the audience. He is going well beyond Andy Warhol’s ego-driven art. Warhol said we could all be famous for 15 minutes. Albert is demanding you make his work of art. He is community minded!

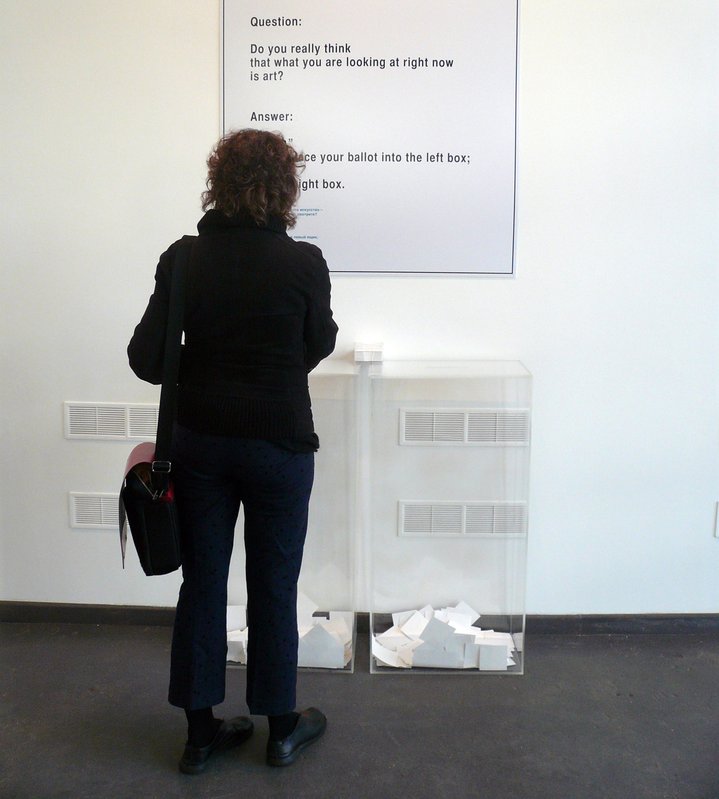

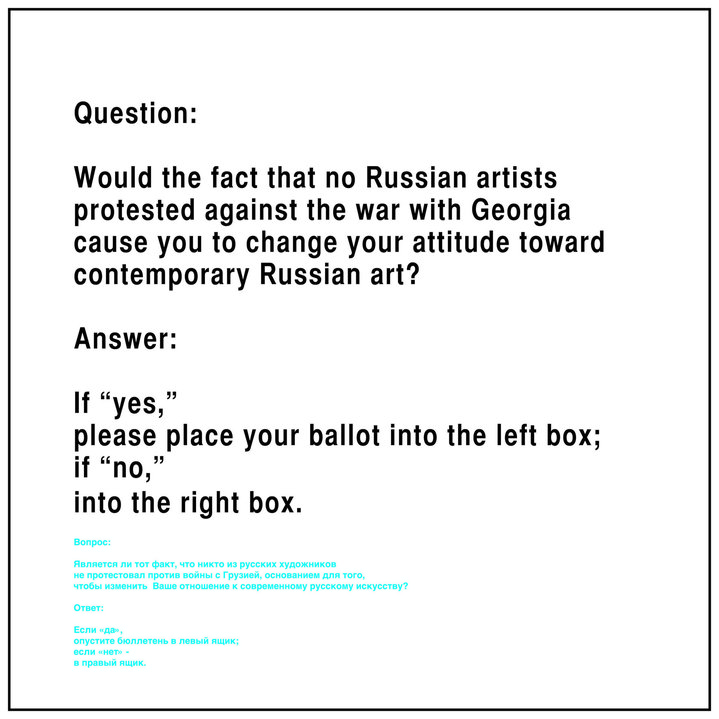

Albert appears at times to be defining himself in negative terms. He is not Lichtenstein, he is not Warhol, he is not Baselitz. The texts may be self-effacing, but the accompanying images are not. Even when the works appear to purely text as in ‘Moscow Poll’, 2009, there is a visual irritation. His last question is: “Do you really think that what you’re looking at right now is art?” He has borrowed the format from a tirade by Hans Haacke. He is an appropriator. “I’ve never produced one single real work of art,” he claimed back in 1987. “All I do is to hint at the possibility of such a thing... I still refrain from taking responsibility for the contents of my works. Or, rather, their contents is love for art. Haven’t you noticed that the subjects of my works are art and the artists?”

Albert’s art may frequently play on other art, but it is never art for art’s sake. He is appropriating old art in order to put the spectator in a new position. He is an artist of our Covid 19 times, as our isolation is one of his most constant themes. He is reaching out to us. He may hide behind official language and signs, but he is doing this as he knows we do it too. Our isolation is our biggest common denominator. For a project in Montenegro once, he simply raised a signpost. In one direction there was the ‘Louvre 1497 km’ and on the other the ‘Metropolitan 7317 km’. When I was writing this profile I asked him, “Do you think since you erected this sign that we are getting closer to civilisation or further away? Are people getting closer to each other, or more remote?” As usual he lances us with his response: “We are not getting closer to civilisation or further away – we are in it, we are part of it.” Yuri Darling is one of the best signposts of today’s world. The message is simple. You don’t have to go looking for love. You don’t need to go looking for art. Just live a little.