Yanina Boldyreva as the angel of dehumanisation

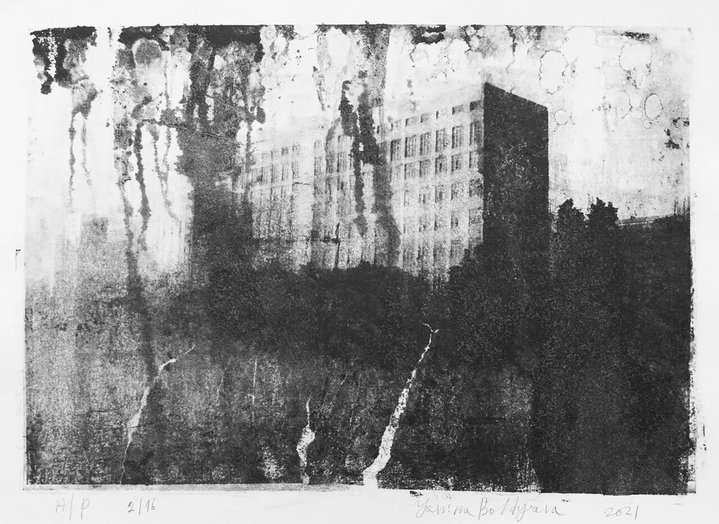

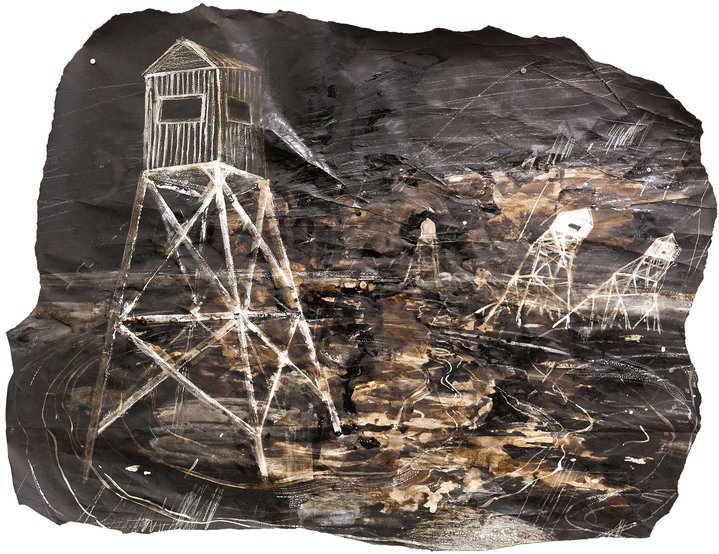

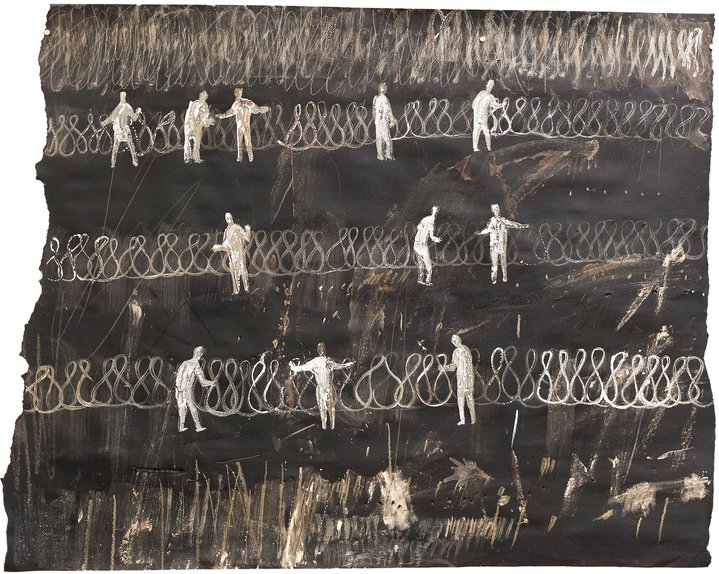

Yanina Boldyreva. Construction, 2022. Mixed media on tar paper. Courtesy of Triumph gallery

A solo exhibition of Siberian artist Yanina Boldyreva at the Triumph gallery in Moscow is a disturbing but timely comment on today’s world.

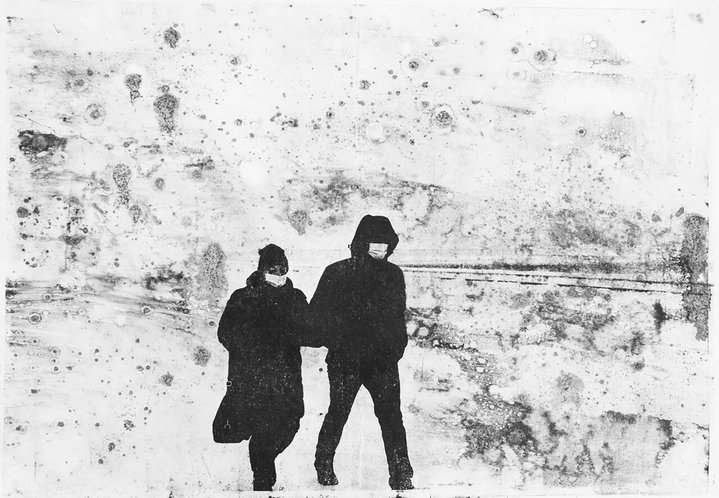

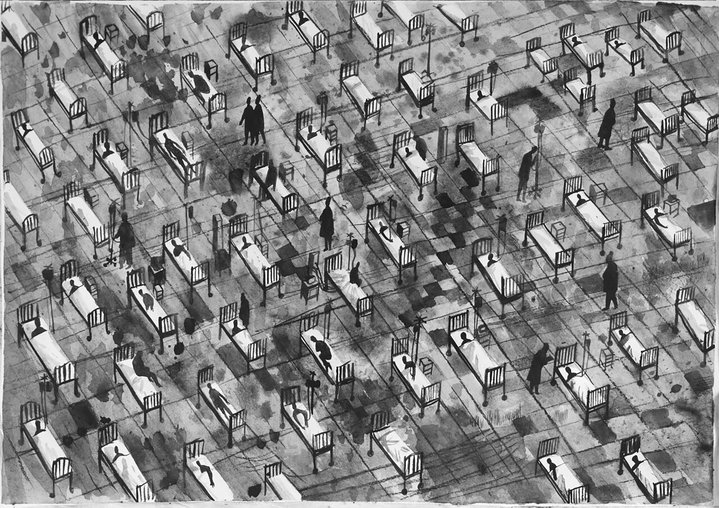

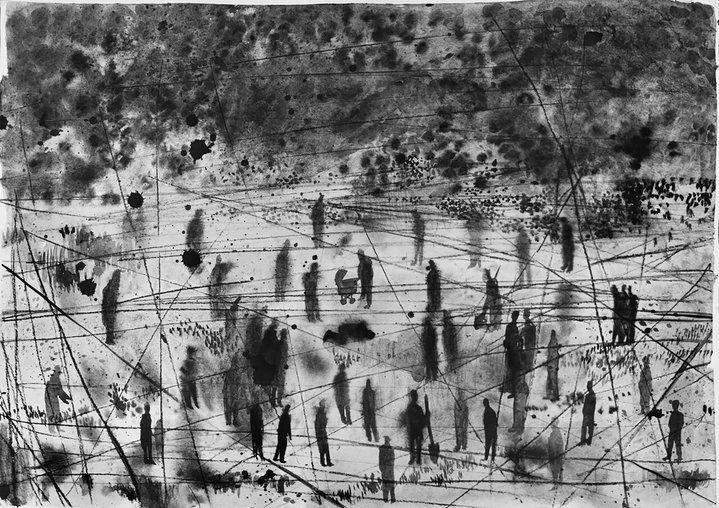

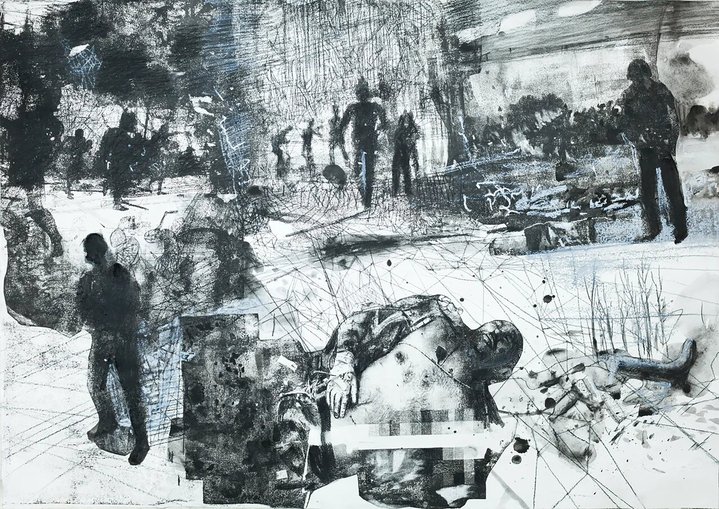

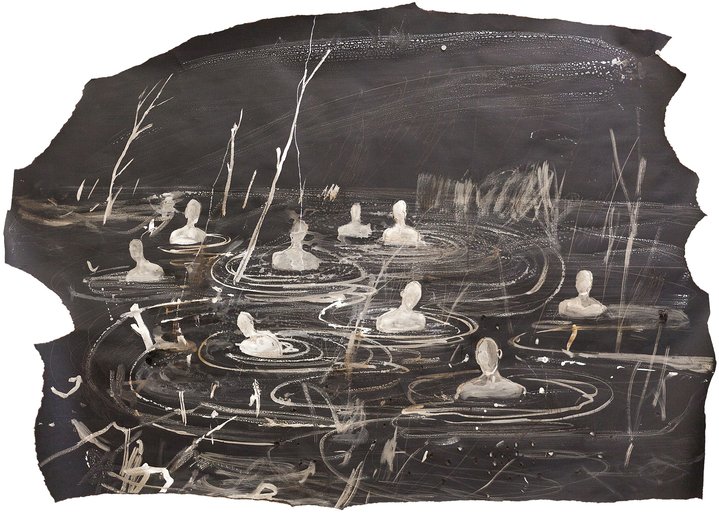

Featureless, pale figures wandering among trees, beating and killing one other, drowning in a marsh (or maybe they are living there), building barbed wire fences, kissing in detention centres, warming themselves by a fire or sitting in a dugout. Drawn in a darker hue, more humans equally devoid of any recognisable features, with the tenacity of Sisyphus, building and dismantling constructions made of the kind of metal fences you see all over Russian cities. These are among the subjects of drawings by Novosibirsk artist Yanina Boldyreva (b. 1986), which are on show until the end of September at the exhibition ‘The Black Calendar’, at the Triumph Gallery in Moscow.

The artist's miserable mood will not come as a surprise to those with even a brief acquaintance with her works. For example, as part of the Teplushka street art project (2019), she painted the interior walls of an abandoned barracks on Voinskaya Street in Novosibirsk. The murals included an image of a parachutist descending from the sky, his face covered by his hands, either out of shame or fear; an invisible man dressed as a detention camp guard; camp guard watch towers in flames; a road to nowhere, with a wooden structure in the middle, resembling gallows; and endless fields of blood-red flowers.

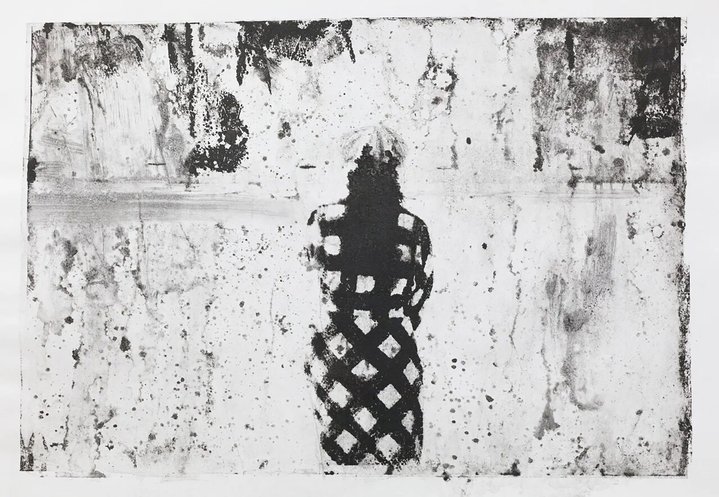

In ‘The Birch Project’ which the artist has been working on since 2021, the protagonists are Birch Men, aggressive, conservative creatures born in the forest. The project consists of staged photography, and some of the birch men are actually played by real people dressed in clothes stylised as the bark of each particular tree. This uniform comes to replace their old identities. They do not hide their faces, but it is as if they no longer exist. This depersonalisation culminates in a photograph of a birch grove where each trunk is covered with colourful ads bearing women’s names in large print and a telephone number. This well-known sign of prostitution covers our cities and serves as the shadowy reality of conservative society.

In a project shown at ‘48 Hours Novosibirsk’ art festival in 2019, Boldyreva showed us where the birchmen were leading us. Against a backdrop of misty landscapes and dimly lit buildings, dark figures advance and retreat, defeat and surrender, but there is no end to the fighting. The world turns into a huge battlefield, but nobody remembers who is fighting and over what. The question is posed by iconic Russian art-rock musician Boris Grebenshchikov, “according to new intelligence data, were we at war with ourselves”?

Here, on the one hand the artist is working with the theme of an authoritarian state and the violence which is pervasive in society, and encouraged by the authorities and accepted by citizens as inevitable. On the other hand, though, the artist’s aesthetics are inherited from the academic school of the Soviet times: from Stalinist socialist realism with its hypocritical claim that ‘life has improved, life has become better’, a phrase uttered by Stalin himself in 1935, on the wake of mass repressions, through the austere style of Khruschev’s Thaw and the ‘noir’ of perestroika, to the post-Soviet stoic acceptance of gloom and tragedy. In this artistic tradition, there is always some trouble lurking around every corner, even if the characters are smiling happily or gazing towards a distant horizon. The world is a trap.

In Boldyreva's work, horrors form a kind of a comic strip, there is a story told in pictures which is descriptive and frightening but not edifying. There is no morality, no hope, or no escape. The universe itself spins in a snare of bad infinity. What's more, many of the characters are conspicuously devoid of any face, lacking soul, a name, opinions or any human dimensions at all. There may be a chilling lack of humanity, but will this even stand out amidst the unstoppable dehumanisation of us in our social networks, in the media, and in everyday life? This process is so pervasive that we do not even notice it. And if you believe that talented artists are like super-sensitive antennas that receive and retransmit the key leitmotifs of the collective unconscious of their time, Boldyreva does indeed capture the uncomfortable truth of our reality, in its most rotten pulp.

In the artist's projects we see everything perhaps through the eyes of the angel of history or an angel of extermination, but it is perhaps more accurate to call this ruthless observer an angel of dehumanization.