Vladimir Kozin and the Riddle of the Mousetrap

In his latest solo project at the Marina Gisich Gallery in St Petersburg, Ukrainian-born Russian artist Vladimir Kozin finds indirect ways to address violence.

“I do not create spiritual values; I’m here to provoke the spectator. My position is to confront my work with what is happening in front of our eyes,” says artist Vladimir Kozin. He was born in 1953 in the Ukrainian city of Lviv and has been living in Leningrad/St Petersburg since 1980. Initially trained as a sculptor, Kozin’s work relates to Pop Art, Conceptualism and Minimalism. Kozin is a patriarch of a Russian-Ukrainian artistic dynasty: his father, the painter Pyotr Kozin (1926–2013) was an Honoured Artist of Ukraine, while his son and daughter-in-law are contemporary Ukrainian designers. Asya Kozina (b.1984) is widely known for her ‘paper fashion’, stage costumes and paper wigs. In the 1990s, Vladimir Kozin was one of the members of the ‘New Dumb’ Artists' Association, and in the following decade founded the very active ‘Parasite’ association, with artist members organizing exhibitions every week.

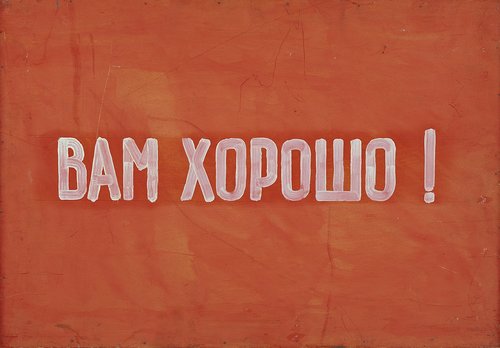

Kozin's last solo exhibition, a retrospective called ‘Feel Like a Bird’, was held at the PERMM Museum of Contemporary Art in the city of Perm in 2019. Now, the exhibition at the Marina Gisich gallery consists of three major projects created by the artist over the past year, two of which will change over the course of the exhibition. The long title, ‘Citizens, be aware, keep your spiritual values safe’ – imitates public transport annoucements, here signaling to the viewer the current protective rhetoric in contemporary Russian political discourse.

In the 1990s, contemporary artists in Russia studied the ABC of European and American modernism, repeating the plastic experiments of the 20th century using improvised means and materials – this local and peculiar version of postmodernism was expressed by the phenomenon of ‘Russian povera’. The term, similar to Italian Arte Povera, was coined by gallerist and cultural curator Marat Guelman (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities), who in 2008 organized an exhibition with this name in Perm, and Kozin’s work was very much a part of this loose movement. Monumentalized in the spirit of pop-art, ‘sculptures of things’ made from black industrial rubber on a wire frame brought the artist fame, it became his ‘brand’ and his work was acquired by museums.

At the Gisich Gallery, his rubber works are exhibited in a section with the paradoxical title ‘White on White’, referring to Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935). In the current project, Kozin has placed each of the objects – predominantly weapons of murder and violence such as a machine gun, handcuffs, axe, knuckles – on black tablets, creating still lifes using the colour scheme of Pierre Soulages (1919–2022).

The museum is perhaps the most natural space for Kozin's art, it is in constant dialogue with art history and world culture, but not quite on an equal footing – it seems to utter its comments from a corner. The main part of the exhibition is called ‘Museum for Mice’. There are twenty-one objects made from wood and wire in the form of mechanical mousetraps named after international contemporary art stars: Marcel Duchamp, Louise Bourgeois, Cy Twombly, Anselm Kiefer, Joseph Beuys, Joseph Cornell, Mark Rothko, Joseph Kosuth, Anthony Tapies, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Sarah Lucas, Louise Nevelson, Alberto Giacometti, Jeff Koons, Robert Rauschenberg, Antony Gormley, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Janis Kounnellis and Meret Oppenheim. Mousetraps have long held a fascination for the artist’ in 2002 he organized a so-called alternative travelling museum ‘Mousetrap of Contemporary Art’, for which various St. Petersburg artists artistically dissected a basic wooden mousetrap, the spring trap on a wooden base.

Kozin is not interested in any institutional critique around his large sculptural objects, for him it is simply a tribute to the artists who have influenced him. The idea for his ‘Museum for Mice’ came to him after visiting New York in 2019 for an exhibition on the history of the New Dumb Artists' Partnership which took place at New York's Mishkin Gallery. He was initially drawn to the large scale works by American artists at MOMA and the Whitney yet admitted: “A Russian artist will never master this kind of scale because he or she lives in a very different environment. For me to be consistent – not to make something massive just after New York – I had to change the scale of perception itself. I wanted to make the viewer feel like a mouse, but I ended up being the little mouse myself," he says. Kozin himself has not caught or killed a single mouse.

The tradition of the ‘little man’ of classical Russian literature, which we are so familiar with in the art of Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933), finds another meaning in Kozin: the modest and hopeless dream of the artist from St. Petersburg who wants to find himself next to the masters whose works fill museums, or at least to stand with them for a while in the back row in a group photo. Not one of Kozin's mousetraps are rigged up – if there is any bait in them, it is invisible; such symbolic cheese is particularly valuable for connoisseurs of art history.

The project culminates with the exhibition ‘Post-Truth’, in which the artist combines works made from news agendas. Kozin has created unmanned aerial vehicles made of wood and named them after heroes of the Russian avant-garde such as Drone 'Malevich', Drone 'Tatlin' and Drone 'Lissitsky'. These pseudo-suprematist works evoke the events over the past year: “They do not fly and do not kill anyone. They are artistic drones, with which I am also internally defending myself”, explains Kozin. His most recent series, which he is still working on, is called ‘Skyline’. These are small models in which the spatial and artistic concept is interpreted metaphorically rather than literally. The horizon line in contemporary Russian reality is distorted, and Vladimir Kozin's inventions can be used to test it.

Vladimir Kozin. Citizens, be aware, keep your spiritual values safe

St.Petersburg, Russia

24 March – 18 June, 2023