Vitaly Pushnitsky: tightrope-walker of a painterly consciousness

A new solo show of St. Petersburg artist Vitaly Pushnitsky seeks to disclose a not-so-obvious kinship between painterly abstraction and death.

When tasked with writing about Vitaly Pushnitsky (b. 1967) I found myself, time and again, returning to a blank wall of obscurity and elusion. Trying to reach out and grasp a kernel of concrete meaning, it slipped through my fingers, proving ephemeral and effervescent. Perhaps – no, certainly – my mental capacity is at fault, but I have Pushnitsky to thank for revealing my inner Socratic paradox. Concerning Pushnitsky’s art, I certainly “know that I know nothing”. Now what remains is to come to terms with it and I might just have a chance to reach enlightenment.

Pushnitsky’s works do seem to offer the promise of enlightenment, but only a faint glimmer, strongly tainted by existential angst, channelling the omnipresent anxiety of modern society through the prism of contemporary art – both a source of energy, a menace, a medium and an antithesis.

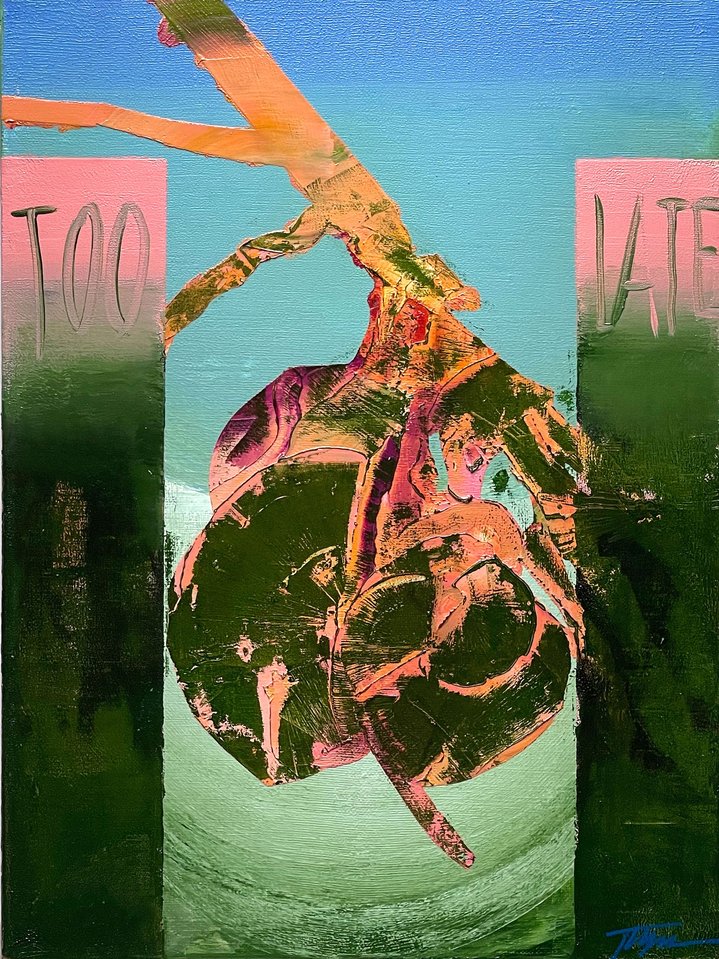

Thus, his forthcoming show ‘Gap at the pop/off/art gallery’ (September 7 – October 16) is about death – ruminations on the potential locus of perception, or dispersal thereof, after the end of the material self. The show includes twenty new abstract works. “They are about how I thought. Or rather didn’t think, but what I did was contemplate the state of what would be if I was dead. And it was a vision of these fields through which my non-body might move.” Immaterial colour fields serve to illustrate the idea that formless abstraction, as pioneered by Turner, is a preparation for death. Because, the artist explains, when light hits a body, it makes a shape, when there is nothing, the light shows only colour. If a picture is worth a thousand words, Pushnitsky's paintings are contemplative philosophical essays, perhaps of a Derridean style, constantly searching for meaning and avoiding conclusiveness. Self-contradictory internal polylogues, where words, thoughts and brushstrokes might be interchangeable.

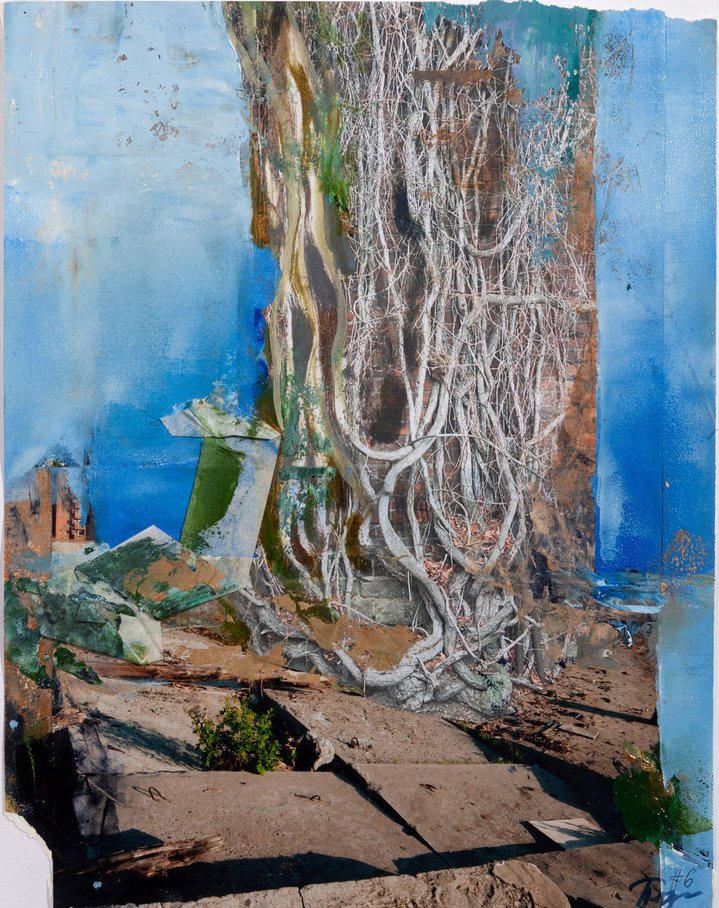

An earlier series Studio Waiting, reveals the artist's strong solipsistic mindset. The large paintings are mainly of interiors with varying degrees of uncanny surrealism, each with some element bearing a sign of the artist’s sacred studio space. “I realised that like most artists I work alone, so I exist in my environment... But, if I am alone in a room, how can I prove that the room is as I see it, there are no witnesses apart from myself. So, in effect, I exist in my own illusion of that room and the fact that I see it doesn’t prove its material existence. I’m not in dialogue with anyone apart from the illusion in my own brain.” The windows are metaphors for eyes and they are blank, because the room is inside his head and the gaze is directed introspectively. The series is an almost ten-year project.

The artist tends to work in series, often several in parallel, manifesting ongoing parallel discourses. “Different series help me keep my balance on the tightrope of consciousness,” Pushnitsky explains, “like a yogi stretching different parts of the body, so I stretch different areas of my consciousness.”

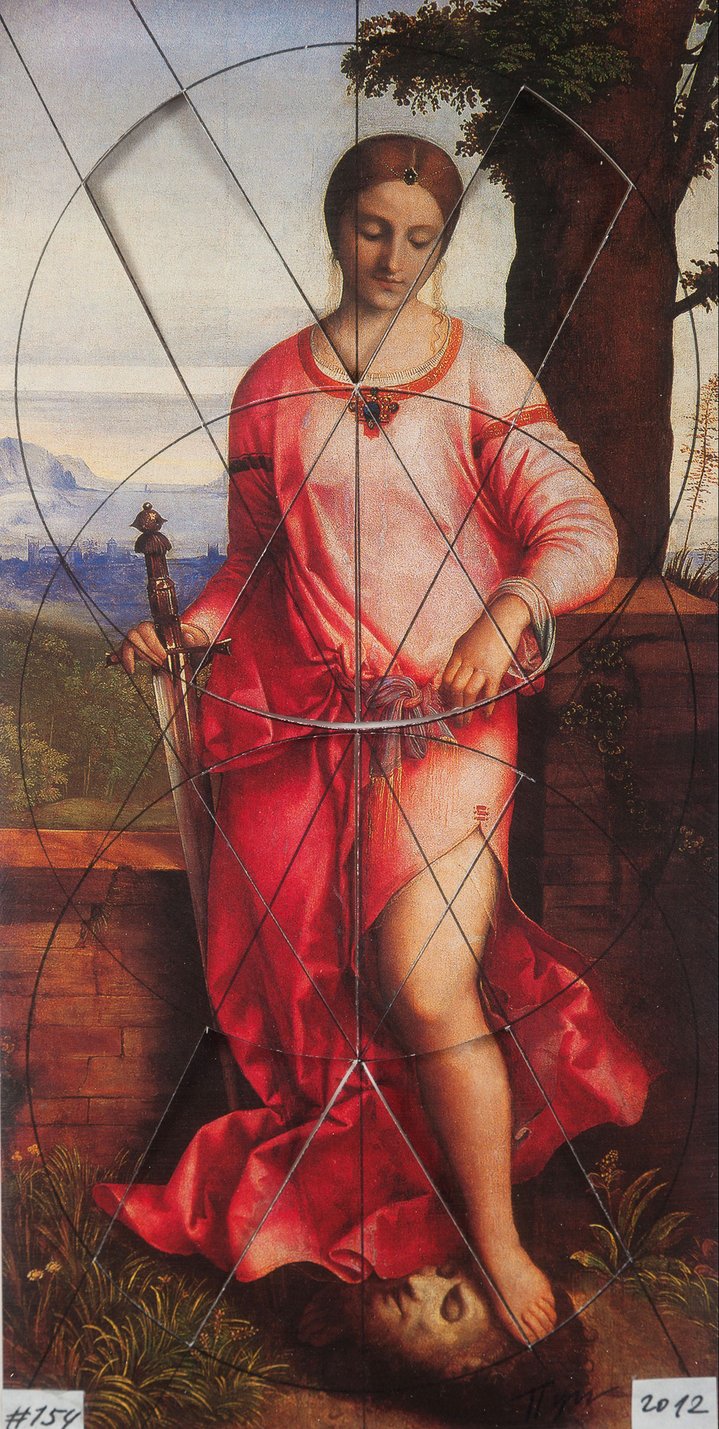

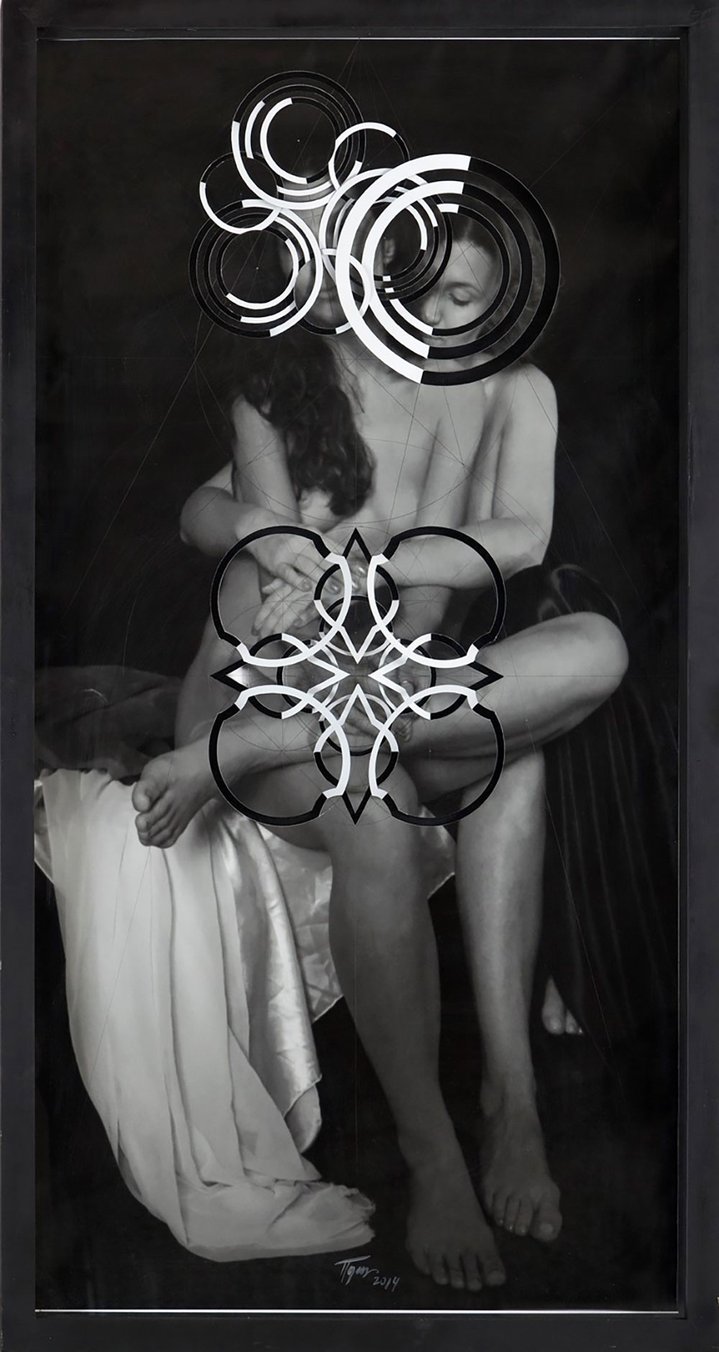

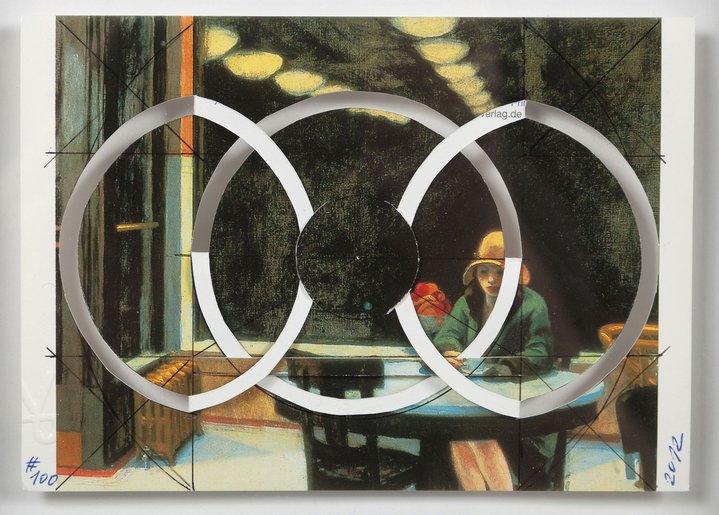

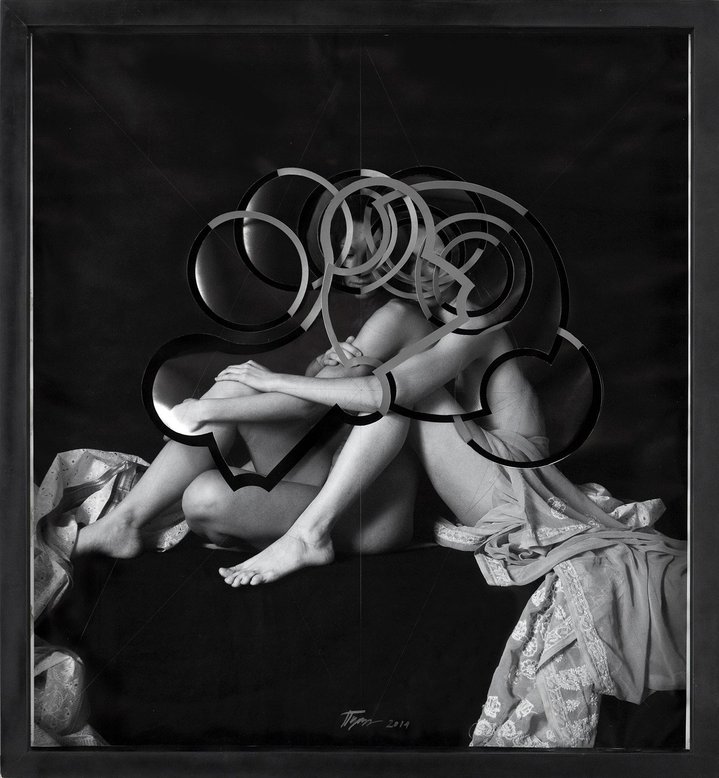

“Every two-to-three years, I go through a crisis, perhaps intentionally, wherein I exhaust my current language and try to find a new one... When I change, I try to contradict expectations, so, in effect, everything I did previously needs to be refuted and rejected. It’s not convenient for my career, but it gives me a certain energy to continue my work.” Pushnitsky continually forces himself out of his comfort zone and grasps at counterintuitive starting points, the things he dislikes. One such series is ‘Points’ (2011–2016): born out of his dislike for the circular form and, hence, all the works are circular. Setting personal challenges, internal antagonism, is his modus operandi. In this vein of inspiration born from a place of discomfort, aversion, rejection – academic painting constantly resurfaces. The series ‘Occam’s Razor’ is telling. Pushnitsky sliced through museum postcards of world-famous classical artworks, creating secondary cut-out paper works from these souvenir reproductions. An iconoclasm worthy of the psychoanalyst’s couch. The artist’s coming-of age coincided with perestroika. Where, on the one hand, one paradigm replaced another and nothing was absolute or stable. And yet, the only option for becoming an artist of any sort was to enrol in the classical Academy of Arts in his hometown of St. Petersburg and study according to the most stringent old-fashioned guidelines. He recalls an anecdote, when he was eighteen in a country village an old babushka stopped him asking, “Young man, I hear you’re an artist, are you?” – “I guess so,” he answered. “Do you paint with oil paints? On a canvas?” – “Yes.” – “Well then you are an artist!”

And it seems she was right, Pushnitsky was included in the esteemed who’s who of painting, Barry Schwabsky’s ‘Vitamin P2. New Perspectives in Painting’ (Phaidon, 2002). But the journey from the babushka’s stamp of approval to inclusion in ‘Vitamin P’ is by no means a direct path, for contemporary painting needs to battle and reinstate all of the previous baggage; destroy and reinvent the wheel, as Pushnitsky puts it, time and time again. A tilting at windmills, which constantly reinvigorates his work. He is inspired and active when he is facing an uphill struggle and, when he reaches a plateau, he moves into a new territory. He channels all of these confrontations, tensions and rejections, many of them internal, absorbed from the two polarities of an academic background and the contemporary art world.

But the idea of contemporary art is an oxymoron, he explains, in Russian, there are different terms – “iskusstvo” (art) and “tvorchestvo” (more akin to creativity). To become art in the former, sacral sense – it must go through death (like Christ, who only became divine through death). That’s why contemporary, living art cannot exist, only creativity (process and generated products). So, Pushnitsky often refers to his works as “products” of creativity rather than art. But carrying the potential to become inscribed into the eternal canon of art after his death. So, is his new show an attempt at a glimpse of his own artistic resurrection?

Pushnitsky rejects the centrality of painting, he says it is not a primary concern. “The material is just a support. It’s like our body, both a prison and a castle.” But this tripartite metaphor where painting is likened to body, to prison-castle is telling. In effect, both body and painting need to be escaped as prisons, yet this is accompanied with the loss of the castle’s safety – essentially death. But then, death is necessary in order to enter the canon of great art. But, if you’re already dead, do you care about what fate awaits your masterpieces? Pushnitsky says he doesn’t...