Vilkin and Begalskaya: Something Else Besides the Monkey

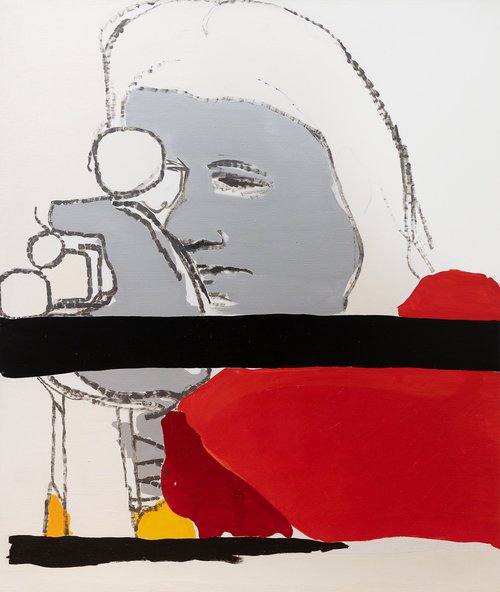

Begalskaya Vika, Vilkin Alexander. The Monkey Goes. Exhibition view. St Petersburg, 2025. Photo by Sergei Misenko. Courtesy of Levashovsky Bread Factory

A thought-provoking exhibition at the Levashovsky Bread Factory in St Petersburg explores the artistic evolution of collaborative duo Alexander Vilkin and Vika Begalskaya, whose refined aesthetics conceal darker themes of the flesh, desire, and humanity's relationship with its primal nature through compelling monkey imagery.

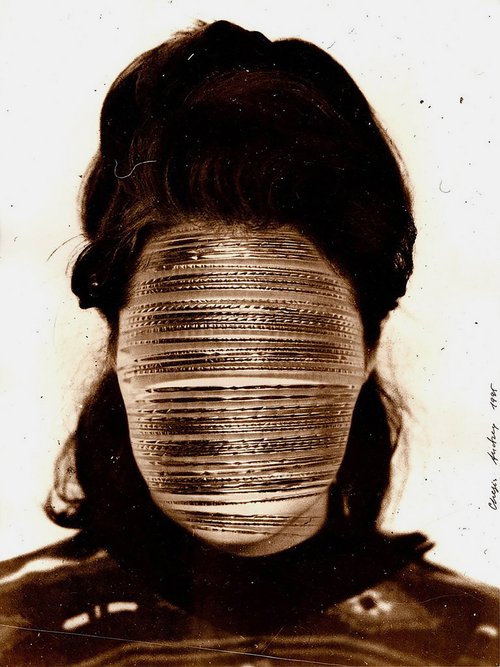

The Levashovsky Bread Factory is an exciting new cultural centre and exhibition space in St Petersburg - a renovated industrial building and listed monument to constructivism (which even houses a memorial to the Siege of Leningrad with a permanent exhibition telling the story of the bread factory during World War II). Currently there are several exhibitions running at the same time: in the boiler room a photography exhibition of work by Vladimir Kupriyanov (1954–2011), a large circular space which once housed massive ovens for baking bread, and there is a small scale yet thought-provoking project by Vika Begalskaya and Alexander Vilkin called ‘The Monkey Goes’.

Artists Alexander Vilkin (b. 1982) and Vika Begalskaya (b. 1975) have been working collaboratively over the past decade as a creative tandem and were shortlisted for the national Innovation prize in 2015. Vilkin was once part of the ‘Prosthesis’ art group alongside Grigory Yushchenko (b. 1986) and Igor Mezheritsky (1956–2020), a subversive punk collective fascinated by the poetics of the lower regions of the body. They created crude works on the theme of violence with a powerful emotional impact which hit you over the head, critiquing mainstream aesthetics, and their exhibitions were accompanied by transgressive performances.

However, today the art of Vilkin and Begalskaya is different. Elegant, aesthetic, refined, often executed in pastel tones, with multiple cultural layers. There are elements drawn from the circus with faces of boars, cockerel heads, masks and snouts suggestive of James Ensor (1860–1949); there is a corporality and carnivalesque quality which references Georges Rouault (1871–1958); there are costume elements and stylish collars evocative of the Dutch Golden Age.

Talking passionately about the work of his ex-collaborator, Grigory Yushchenko reflects: “Many years ago at the opening of Alexander Vilkin’s exhibition, an inflatable sheep from a sex shop hung from the ceiling, a DJ in tights and a police cap played songs whose titles are now unsafe to mention, and beautiful intoxicated female bacchantes urinated on even more intoxicated young men. The works themselves depicted roughly the same thing: brightly coloured characters indulging in a spectacular whirlwind of perversions, bodily secretions and carnivalesque violence. ‘The Bride Was Pissed On’, ‘Harry Potter and the Vacuum Pump’, ‘Peep Show at the STD Clinic’ – memorable captions complemented these cheerful pictures.

It seems that in the collaborative works of Alexander Vilkin and Vika Begalskaya, the intentions of the above-described character relationships are preserved, but they are buried under layers of patina, ochre, sepia, blur. They have drowned like insects in amber. The paints sink into unprimed canvases and plywood. Their preservation is accompanied by muteness; letters have disappeared from the painterly space. In Borges's ‘The Book of Imaginary Beings’, there is a Chinese legend, I believe, about a beyond-the-mirror tribe that will emerge from captivity and break free from the prison of amalgam when some anticipated time of Armageddon arrives. It would be tempting to think that something similar will happen to the characters in the works of the duo Vilkin-Begalskaya...”

So, although on the surface their artistic form has become more refined, inside we actually find much the same: a monstrous, mesmerising world of flesh and lust, both alluring and repulsive.

A monkey is the central motif in the exhibition at the Levashovsky Bread Factory. It is not a random image, there is a centuries’ old history. The moralising 17th century paintings, where monkeys wearing feathered hats hold court in kitchens, symbolising greed and parodying the social hierarchy. The monkey was viewed as an imitator, mindlessly copying human actions. In the canvases of David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690), monkeys drink wine, play cards, and engage in the arts. For artists, introducing the image of the monkey often became a way to give the painting didactic content and to introduce a moralising dimension. The monkey was frequently perceived as a symbol of vice; it was depicted with an apple in its paws, reminiscent of the fall from grace. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) has an engraving called ‘Madonna with a Monkey’, where the chained animal becomes a sign of subdued passions. In medieval Europe, the maxim “the devil is God's ape” (Diabolus est simia Dei) emerged; theological treatises speak of the monkey-Lucifer.

In Vilkin and Begalskaya’s work, monkeys can be courtly tricksters, or they can control life and death. In their 2021 work ‘Ritual’, the monkeys resemble devils; in ‘Oliver’ made the following year, a monkey-sorcerer makes human skulls levitate.

In their 2021 work ‘Hunter’, the monkey is more of a magical helper. In the canvas, a human finds himself in a common semantic field with plants, birds, and a monkey; they merge into a single organism. Flowers or some kind of shoots burst from the hunter’s mouth, birds perch on his hands, mistaking them for branches, the monkey embraces the human figure from behind, and it is unclear which are human arms and which are paws. The result is some kind of Shiva, containing both mercy – unity with nature – and destruction, the bow in the hands of a hunter.

In ‘Cigarette Buba’ (2022), a tame monkey wearing a jester’s cap is smoking, with large protruding lips. The surface of the canvas itself, in turn, appears to have been burnt all over with a cigarette end.

In the painting ‘Barbe’ (2022), the monkey looks very human; it wears a shirt with collar and uses a toothbrush to groom the main character’s head (this gentle interaction is termed grooming in anthropology). The female head, conversely, appears to embody the bestial principle. Green face, bulging eyes, yellow teeth, which the character picks at with a finger, like a monkey. Human and animal exchange places; here the monkey/human reversal developed by the artists is uncharacteristically overt.

‘Ventriloquism’ (2021–2022) is a strange painting which depicts a monkey standing on a stage and holding a doll or perhaps the figure of a girl, showing it off to the viewers as though it is a human holding a monkey on its shoulder in a circus or zoo to entertain children. The doll is hypnotised or in a trance, performing ventriloquism in this inverted world.

Most of the works presented in ‘The Monkey Goes’ were created in 2022, shaped by well-known tragic events, and many are coloured green reminiscent of military uniforms. So, who is the monkey in this exhibition: the devil, vice, a monstrous double, dehumanisation, war, or the end of the world? When I put this question to the artists, Vilkin avoided a direct answer and using evasive expressions, inviting us to expand the meaning of what we see.

“In fact, monkeys appeared in our work long ago, and it is difficult to generalise and if there ever was a primary meaning in the beginning then now it is lost. You could say this is a figure of potentials (failures), of bipedalism which exists in a state of becoming and transformation, like us and paintings themselves among other things. A figure that has become aware of its own nakedness. It is not even about the monkey anymore. But often it is a trick [so as] not to depict something else. Is there something else there besides the monkey?”

Begalskaya Vika, Vilkin Alexander. The Monkey Goes

St Petersburg, Russia

2 August – 21 September 2025