Viktor Pivovarov with his work “Malevich in the snow” (1997). 2015. Photo by Ekaterina Wagner

Viktor Pivovarov’s walk down memory lane

Russian conceptualist returns to Moscow with new works and reminiscences of the old

For the 81-year-old Russian artist Viktor Pivovarov, the only place that exists on earth is Moscow, whereas he has no concept of Russia. This is because only Moscow is real, as he explained in a 2001 autobiography.

The clue to this vision is the subject of Pivovarov’s latest exhibition which opened on October 23 at the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow and which he dedicated to the Moscow Intelligentsia. The show will close on February 3, 2019. That this body of intellectuals still exists despite Stalin’s purges and that a sufficient number of its members resisted the temptation to worship Mammon after the collapse of the Soviet Union is nothing less than miraculous.

It is Pivovarov’s old friend and fellow artist, Ilya Kabakov, who in a recent documentary film captures the extraordinary pull of Moscow intellectuals. In it, Kabakov complains that having moved to the United States, the only person he can talk to is his wife. In his new country, people come to “visit,” but no one comes to argue through the night and then start again in the morning and continue until the next dawn, as they did so regularly in his Moscow years. The Moscow intellectuals these artists have in mind retain the thrill of their student days and it is that energy and heady, intoxicating atmosphere created by empty bottles and round-the-clock cerebral jousting that the exiles miss most.

Pivovarov left Moscow for Prague in 1982 after meeting his second wife, Milena, who is Czech. As soon as he applied to leave the Soviet Union, he was kicked out of the country’s Union of Artists. However, he has since returned to Moscow every year, to “recharge his batteries,” as he puts it. He craves the reflections of the sun on Moscow’s tin roofs and what he calls the city’s “uniquely deep skies” even though few traces of how the centre of Moscow looked in Soviet times have survived. It is almost irrecognizable due to multiple facelifts that have smartened the city’s old heart. Pivovarov’s solution is therefore to take Moscow with him wherever he goes.

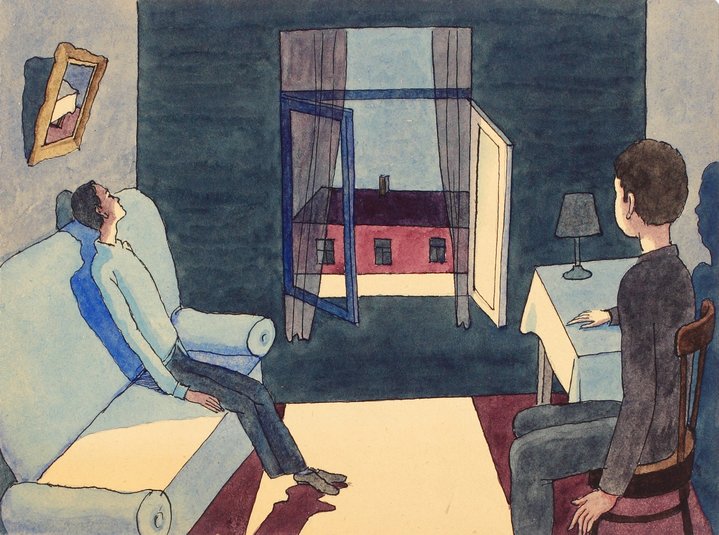

This Moscow exhibition for instance includes three of Pivovarov’s gently ironical “Albums.” One, created in 2005–2010, is about Florence where the poet Dante is acting as a kind of tourist guide for the artist and two long-dead Russian contemporary poets who were Pivovarov’s close friends. In the artist’s Florence, one catches glances of Soviet high-rise blocks squeezed into narrow Florentine lanes. In one picture of that album, a deep-blue van is parked on Via Santa Margherita. It is in fact the twin of one of Pivovarov’s childhood memories, a dark van left on a narrow lane near the communal flat where he and his mother shared a room. In 1985, Pivovarov painted the ramshackle van he had seen as a child. It belonged to a dying breed of merchants who used to roam Moscow courtyards as late as in the 1960s, calling out for anyone who had “old” things to sell.

In Soviet times, he never wanted to be a “dissident” artist. He recalls in his autobiography how when the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia took place in August 1968, two poets and the non-conformist artist Vladimir Yankilevsky, who died last January in Paris, came to his studio. A small group of dissidents had just staged a brief protest on Red Square and were immediately arrested. The question was how to react. It was settled by Yankilevsky who said that if the dissidents’ protest was an act of civic courage, then painting pictures every day would be no less so.

Six years later, Pivovarov shunned the path-breaking “Bull-dozer exhibition” in a waste ground on the outskirts of Moscow in September 1974 although most of his artist friends took part. The violent break-up of that exhibition by the police who smashed the paintings and threw them into rubbish vans caused an international scandal. Within days the Soviet authorities allowed the same artists to stage a very brief show at the Izmailovsky Park market. A very small window had for the first time opened for non-conformist artists.

The only reference to repression by the Soviet regime at Pivovarov’s Moscow exhibition is a portrait the artist Ivan Chuikov being interrogated in the offices of the KGB. Chuikov had been one of the organisers of the “Bull-dozer” show. The Chuikov portrait is included in Pivovarov’s 1996 Album whose name translates as “Dramatis Personae.”

Pivovarov later acknowledged he had made a mistake boycotting that exhibition. He had been put off by what he called the “collective euphoria” surrounding the event. He said he should have taken part because it was really a moral stand and not just an artistic statement.

Pivovarov is not so much nostalgic as deeply attached to his roots. He never found out who his father was, but hero-worshipped his mother who worked on the floor of the “Paris Commune” shoe factory which is still in business on the south bank of the Moscow river.

At the opening of this Moscow exhibition, Pivovarov made an unexpected appearance in the main hall he had covered with paintings of absent-minded Moscow intellectuals, created in 2017 for this show. He plunged into the crowd and started explaining why in an exhibition honouring the Moscow intelligentsia there were so many small, as he called them, “Suprematist” paintings of factories. It was of course because of his Mum’s work in the “Paris Commune,” but it was also a tribute to one of Malevich’s Suprematist pupils, Ivan Kliun, who at one point worked as a book-keeper at the same factory, something not mentioned in biographies.

It is the typical erudite touch of an artist who is a deep thinker but who rejects being labelled as a philosopher. The press release for the exhibition describes Pivovarov as a “Moscow Romantic Conceptualist.” Labels are suspect, but he does consider himself a conceptualist. What is certain is that he is a Romantic. “Childhood and Moscow are one thing for me,” Pivovarov stated in his autobiography. It is the key to an artist who became one of the Soviet Union’s most famous illustrators of children’s books. His memories are his roots and in the 1990s he said he had finally returned to the lost Paradise of his childhood.

At a dinner after this Moscow opening, Pivovarov made a speech in which he said his latest exhibition only made sense in Moscow and nowhere else. It is through that looking glass that his work should be judged.