Valery Dudakov: Art as a Religion

Valery Dudakov. Photo Gleb Anfilov

Valery Dudakov is a raconteur with an Abe Lincoln beard, whose tales of art collecting reflect the ideological ambiguity of the Soviet-era and the uncertainties of today’s Russia.

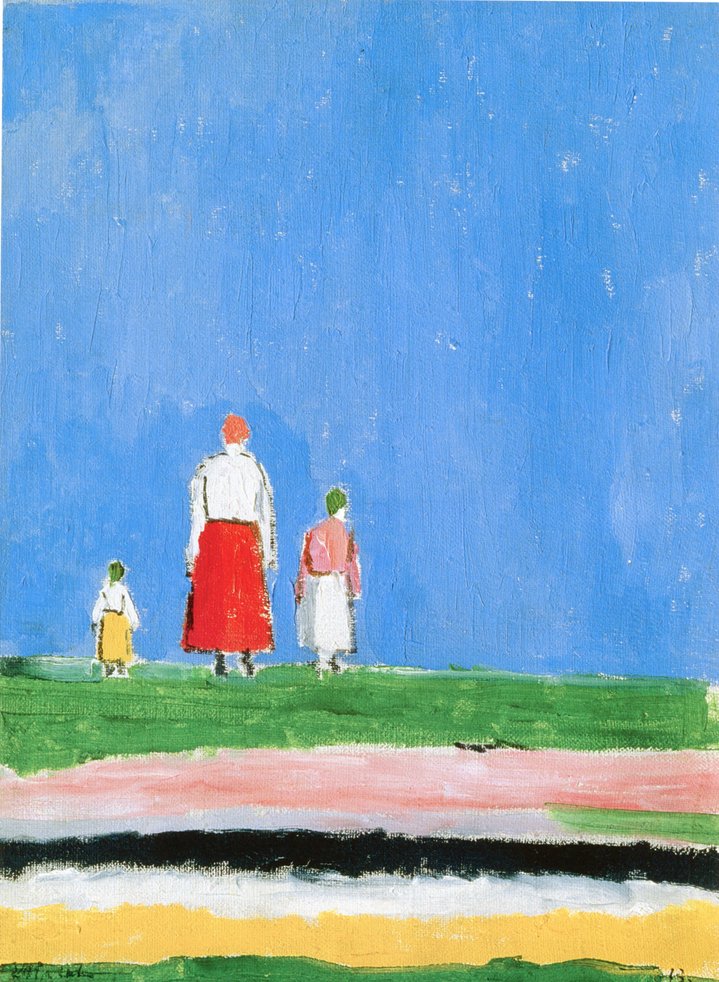

He is famous for both his personal art collection and his career as an art consultant. The former was built over decades, with a focus split between the pre-1917 Golubaya Roza (Blue Rose) Symbolist movement and the artists known as "shestidesyatniki" ("artists of the sixties"), who broke free of the creative strictures of Stalinism after the Soviet dictator's death in 1953 and earned their collective name in the relative freedom of the early 1960s, thanks to Nikita Khrushchev’s Thaw.

“Very many started collecting after Stalin died,” Mr. Dudakov told Russian Art Focus. “Why? First of all, because a certain sense arose of a freer way of life.” Withinmonths of the dictator’s death, according to the collector, formerly banned Impressionist paintings were on show at the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, joined in 1956 by Picasso himself. “Imagine how quickly things changed,” he said. The shestidesyatniki included Vladimir Nemukhin and Oskar Rabin, who died recently, as well as Francisco Infante, with whom Dudakov attended a Soviet Young Pioneer camp as a teenager.

Dudakov intended to open an art gallery called Nepokorniye (Indomitable) this year to highlight his shestidesyatniki collection, but the initial plan ran into problems. He has not given up the idea, but cannot find a suitable space — mainly because he insists it should be next to his flat where he lives with his Blue Rose collection. He says that this is a nervous time for collectors. A growing number of private museums displaying collections amassed by Russia’s post-Soviet wealthy class masks an overall sense of anxiety, with many keeping prized possessions out of sight or abroad. Until recently, Mr. Dudakov kept a London apartment as a base from which to travel the world and buy art for billionaire clients.

“Right now, the situation in society is such that collectors strive to keep a low profile,” he said. “Our authorities are capable of all kinds of trickery.”

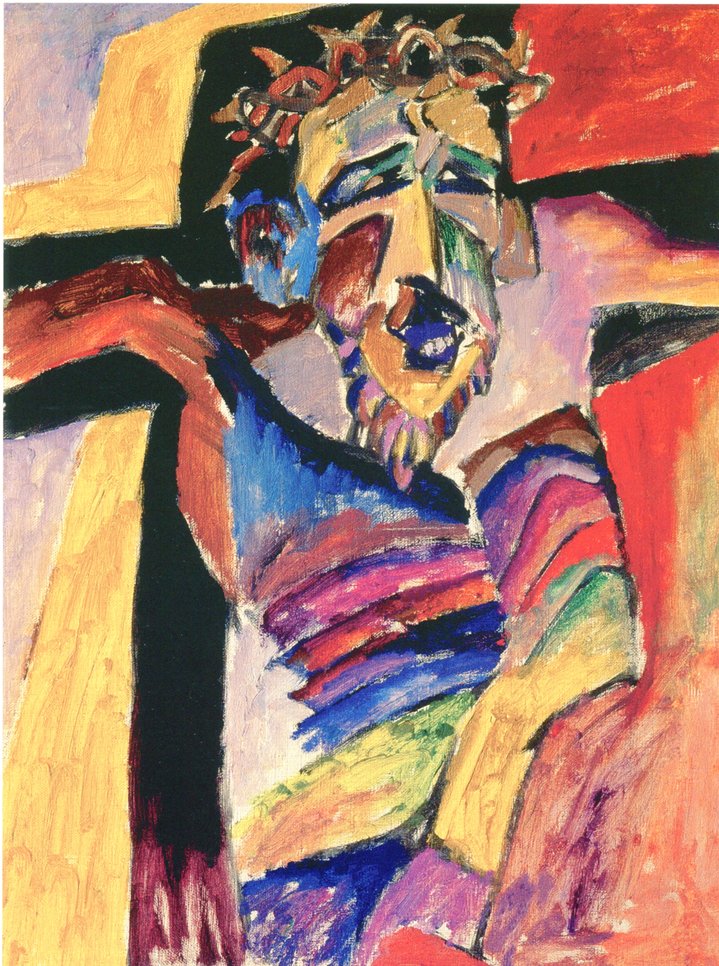

Dudakov had close friendships with artists, including Rabin and Nemukhin, and the latter served as an important guide to understanding art. He also pointed Dudakov to a subsequently seminal figure, Vladimir Weisberg (1924–1985), a metaphysical painter mainly known for his later, ghostly white compositions.

“How did my collecting start? Nemukhin introduced me to Weisberg. Nemukhin said ‘I don’t know what will happen to us, but he will sell.’ It was 1970, and it was the first oil painting I bought in my life,” Dudakov explained. A graduate of graphic design school and Moscow State University’s art history department, Dudakov went from a family with no connection to art to working for Melodiya, the Soviet record company, eventually becoming its chief artist. The job afforded an extremely comfortable salary by Communist standards, and he joined and then led a rarefied group of collectors, ranging from academics to Soviet officials, some of whom got away with surprisingly progressive tastes in art. According to Dudakov, the late Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev dismissed complaints about the art collecting habits of Vladimir Semyonov, a Soviet diplomat and key nuclear arms treaty negotiator in the 1970s.

Dudakov knocks down myths about Soviet-era collecting, saying collectors often flourished and if they were targeted, it was on political grounds, rather than because of their collecting passions. Every painting in his collection has a story, which he generously shares, and he continues to loan his works for exhibitions. The Chagall on his wall cost 13,000 rubles, the Soviet equivalent of about two cars in 1983 — a relative bargain at a time when art prices had begun to rise. A painting by Aristarkh Lentulov, an artist who was initially part of the Russian Avant-Garde, was purchased in the second half of the 1970s from the artist’s daughter for just 1,000 rubles. Drawings by Mikhail Larionov could be had for a little as eight rubles, the cost of about two bottles of vodka. Prices shifted to dollars long ago (although owning hard currency was illegal in Soviet times). Just four years ago, Mr. Dudakov was offered $5 million for a painting by Armenian artist Martiros Saryan that he originally purchased for $100,000 in the 1990s.

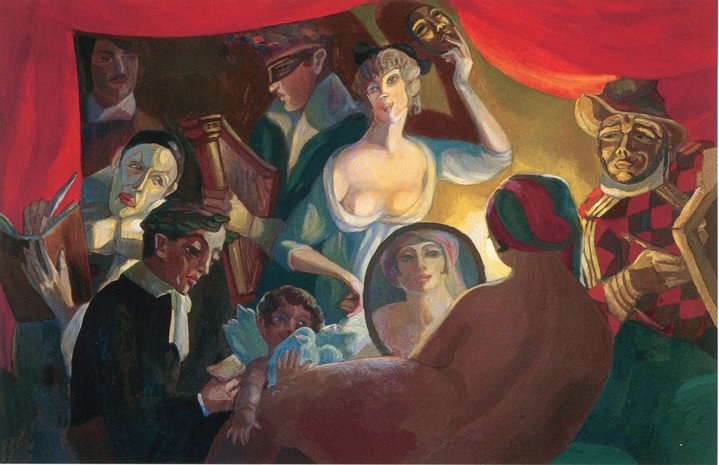

“It’s likely he’s not even worth that much, but I will never sell him, even for $10 million,” he said. “Because this is a rare work that I will never have again." Another piece by Sergei Sudeikin, known for his stage designs for the Ballets Russes, was bought in the late 1970s for 14,000 rubles (then the price of a three-story stone dacha), but is yet another work which he is unlikely to part with.

Perestroika saw him seize the chance to organise dozens of exhibitions of Russian art from private collections through an institution called the Cultural Foundation, which was closely associated with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa. It was a major breakthrough in what had for so long been a hermetically closed country, and Dudakov himself regards these as his highest achievement. The low point seems to have come later, when Dudakov reinvented himself as an art scout for Mikhail Khodorkovsky, one of Russia’s most successful oligarchs (until he ran afoul of President Putin and was jailed in 2003). Khodorkovsky was eventually released in 2013 and flown out of Russia, but almost nothing is known about Khodorkovsky’s art collection. Dudakov said the job was deeply depressing and drove him to drink.

Today, Dudakov describes himself modestly as a simple pensioner. He occasionally shares his experiences in public, often in literary form (he is also a poet and writer), conveying his main message: art must be cherished. “Love the art in yourself and not yourself in the art,” he says, repeating a motto coined by the great Russian theatre director Konstantin Stanislavski (1863–1938). “For me, art is a religion.”