Valery Chtak. Photo by Elena Avdeeva

Valery Chtak, ‘I don’t want to say anything – I’m a Dadaist’

Cosmoscow Artist of the Year, Valery Chtak is unveiling a solo exhibition at the Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries in Moscow. He talks about his artistic practice in an interview which was originally published in our sister publication, The Art Newspaper Russia, in September 2022.

Moscow artist Valery Chtak was born in 1981. From 1998 to 1999 he attended Avdey Ter-Oganyan's (b. 1961) School of Contemporary Art. Between 2000 and 2005 he was a member of the Radek Society, a leftist art group around Radek magazine. His works can be found in the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantin Sorokin Foundation, the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Daugavpils and in the collection of Deutsche Bank.

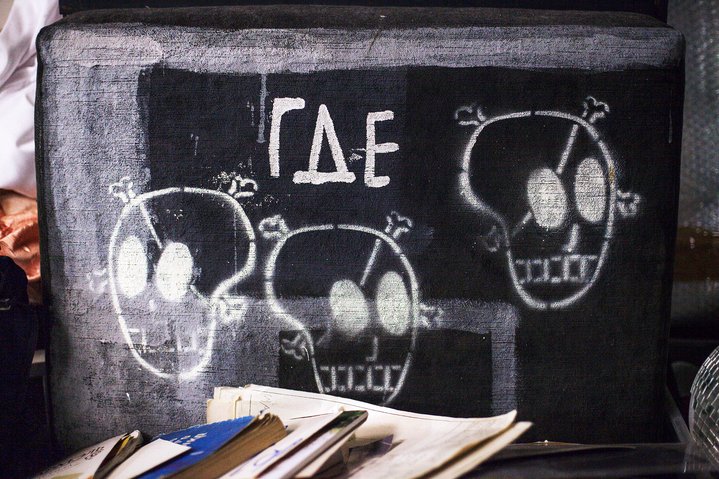

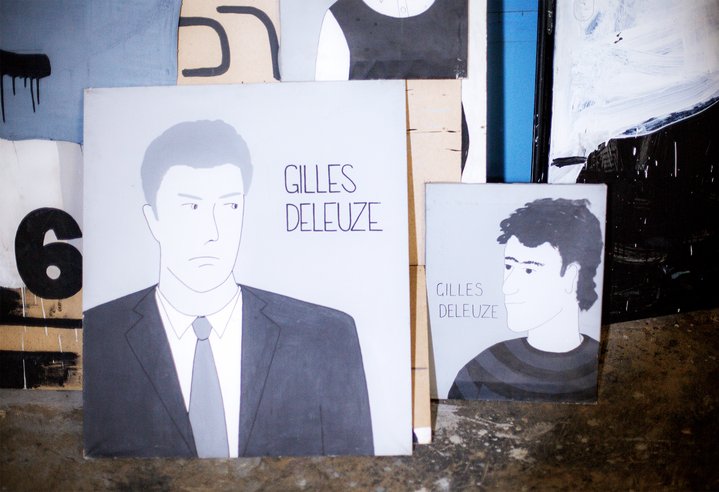

It is easy to recognize his work, it’s conceptual, monochrome with witty and odd phrases written in different languages. “Everything is gray, there are some random letters...you cannot understand anything but it's funny,” is how Chtak himself describes them. Many people think he was initially a graffiti artist, so he starts by giving a warning shot that he has nothing to do with street art. We met in the artist's studio and talked about art - his and art in general.

You once said that you like to give interviews because you like a good rant.

Yes, I love to rant. Ranting is great. You know, it's good to throw carbide in water. If you just throw carbide, nothing happens, you’ve got to throw it into water. It's the same with ranting. If someone listens to you at that moment, a chemical reaction will take place.

Then let’s rant. Tell me, is textual art also an opportunity to let off steam in a sanctioned way? For example, one of your works has the absurd phrase “mosquitoes eat mushrooms” …

Yes, yes, it is. Especially with an official status like ‘artist of the year’. As your value on the market goes up, you are invited to talk more and more. It's like Damien Hirst. First you go for sharks, then pills, then butterflies, then something else, and then everyone thinks: ‘So, Damien Hirst is a name that sells, ok, we'll push the boundaries and let him do what he wants.’ So, he does what he wants. And this doesn't just work for the Young British Artists or other Chapman Brothers. It works in smaller cases too. You're allowed to say things that are conceptually out of place and unconventional.

Since we are talking about status, what do you think about Cosmoscow nominating you ‘artist of the year’?

This year you are the artist of the year, next year someone else will be. It's like you were appointed a colonel, without a regiment. It's good that it happened, it means my value is being recognized by someone although I did not enter the competition myself, I just got a call. Being ‘best artist’ is like being the ‘tallest dwarf’. Then you step outside Cosmoscow, where you were just being awarded honours and recognition, where people were asking you for an autograph and you walk into a shop, ‘Do you need a bag? Chtak? What? Who's that?’ Caravaggio was not recognized as a great painter, one of the fundamentally important figures of the Baroque until 300 years after his death. 300! When he was alive, he just walked around with a sword and killed people and got into fights. I'm certainly no Caravaggio but imagine if someone discovered my paintings 300 years later! “What's that? Is that written in French? Oh, yes, there was such language in the ancient times!”

Speaking of French. There are words and phrases in your works in many languages other than Russian and English.

I don't speak any of the languages I use. I only understand and speak English fluently.

I have a theory that this is such a paradoxical move that allows you to come close to not understanding your own work.

Well, I don't write just any old cluster of words, I am aware of the translation.

Do you ever forget the meaning?

I do. All the time. Especially if it's written in Korean or Amharic. What does it say? I can't even read it. Because it's syllabic. I can read in Georgian, in Hebrew, in Yiddish... Someone might have written something down in Armenian, I copy it out, it looks correct and an Armenian says ‘ok’ and then I forget what it means, and I can't read it anymore.

You know, James Joyce, who wrote ‘Finnegan's Wake’ using dozens of languages, couldn't decipher individual fragments afterwards either.

That's a very flattering analogy. Yes, and he also deliberately underlined words and phrases with different coloured pencils so as not to get confused.

Your artistic initiation by fire was in 1998 at Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street, during the famous Barricade action organized by Anatoly Osmolovsky and Avdey Ter-Oganyan. At the time you were only 16. How did you get into this exclusive club of hard core protesters?

By chance. Everything in my life has happened by chance, and often by chance I have made good choices. Sometimes I have accidentally made the wrong one, in fact also many times. But often the right one. David Ter-Oganyan came to visit us in the 11th grade and brought me to his father, Avdey, and then Avdey brought me into the Barricade and everything else. So, whatever his views are now, Avdey is in my life.

Today, Barricade would not be perceived as an artistic action, but exclusively as a political one.

Even at the time of the Barricade action I saw that there was no real struggle. There was only the image of a struggle. The police came only once, looked around, and then left. They came a second time, took another look, and left. This went on a few times. And I realized that there was no resistance in the art community. It was just a revolutionary theatrical production. And then the Radek group came along and we kind of created a resistance. A Revolution and all that. But mostly in the form of getting drunk and throwing stones at suburban trains. It was that kind of protest. On the whole, when you're young you have to do that: climb up somewhere, put a flag there ... But as you get older, it all goes away.

I must say that at that time there was less chance that a stone thrown at a train would ricochet right in your face.

In the 25 years or so I’ve been active in the art world I've learned an important lesson: if you don’t touch religion or the authorities, they don't care who you are or what you do. There's a vicious dog in the yard and if you tease it, of course it gets angry. But if you just walk back and forth across the yard... I don't remember having any problems with the authorities specifically related to art. Look at this: what year was the picture made in? It's only just been finished, but there is no stamp of time. None at all. It could have been painted in the 1960s or the late 1980s. That's what I do. You can only understand my personal history from a picture, not the history of the state. Resistance, revolution is hard work. Not something made by infantile graduates of modern art schools. I don't want to offend anyone, but if you want to get into resistance and politics, you will do just that.

How is it that, having started out in the early days of Actionism and with such teachers, you ended up being a Conceptualist?

For me actionism was just an entry point. When you're sixteen you're very susceptible and malleable. I used to say at the time: “I'm an artist, but I don't paint, I'm a member of an art group". That's how it was. And then I started painting. And I realized that is what I wanted to do.

You also play in a rock band with the almost unpronounceable name Sthow's Seths. I bet you came up with that one.

Yes, I did. Just to make it hard to pronounce.

Can you decipher it?

Mister Sthow is my character. It's a cool dude with a hat who shows up in my work from time to time. (He shows a tattoo of him on his arm.)

And Seths (Seths) - is it from ancient Egyptian mythology?

No. There is a Hebrew name, Seth. He was the third son of Adam and Eve. It is written in the plural form. So, there are three of us: me, the bass player, and the drummer - we are some Seths of this Stow. The bass is played by Zhenya Kukoverov from EliKuka art group, and the drums are played by Mitya Vlasik (a Russian composer and performer of contemporary academic music). And I play the guitar.

Judging by the drum kit and the guitar behind your back, you rehearse right here in the studio?

Yes, but we call it practicing, not rehearsing. Because we practice playing together. And it's always a kind of improvisation.

As a final chord, why don't you improvise about art?

Art is if you take two magnets and bring the same poles close together. Then you get a kind of z-z-z-z-z like a balloon. It doesn't make any sense, it's completely wrong. You can turn one around so the opposite poles meet and then they will stick together. Just like that you get a design. And if it's positive to positive or negative to negative you get this kind of zzzzzzzzz. There, that's it. What is it? This is it. That's the art. That's how I'd describe it, as a moment which is hard to capture. I've coined a phrase: “Not less than you, and not today”. I like it because it doesn't make any sense at all. I understand each word individually, but what do I want to say? I don't want to say anything, I'm a Dadaist. Sometimes people ask me, “Why is it like this?” I don't know, it's just funny! That's what Dadaism is. It's cooler if it is like that than if it’s not like that or than if there was nothing at all. That's the only principle of how to make art. It’s better to have this painting on earth than not.

Valery Chtak. PGT

Fabrika Centre for Creative Industries

Moscow, Russia

September 9 –November 30, 2022

Cosmoscow International Contemporary Art Fair

Gostyny Dvor exhibition centre

Moscow, Russia

September 15–17, 2022