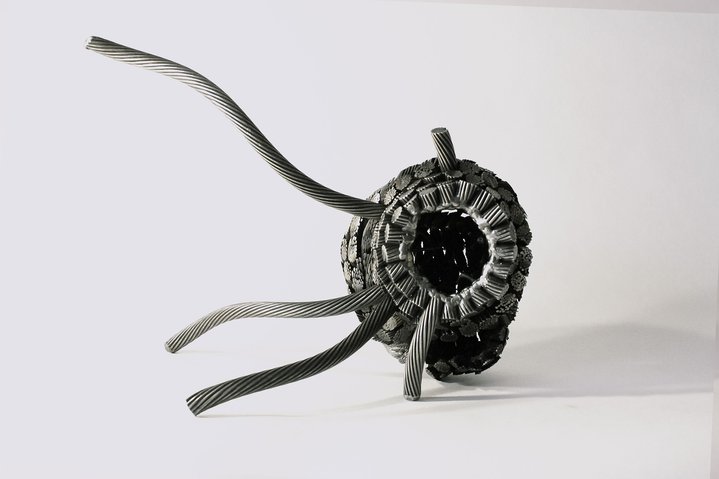

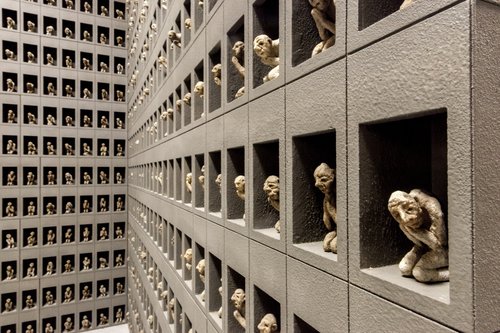

Vadim Kondakov. House Plants, 2020. Courtesy of the artist

Vadim Kondakov Is Letting Metal Loose

This young New York based sculptor follows the internal logic of the materials he uses, giving them freedom to rust - and to rest.

A small, dilapidated basement in a detached house on Staten Island, New York, looks like the home office of a car mechanic. Vadim Kondakov (b. 1990), art handler at the Guggenheim by day, texture alchemist by the time he gets home, shows me around the objects, the chemical compounds, and the tools he uses to create his laconic and highly original abstract sculptures. Kondakov arrived in the US shortly after the war in Ukraine started, and for several months he had persistent doubts about whether he would ever continue to make art. “The Guggenheim opens its doors in the morning, crowds of smiling people all over the world flock in, and I’m sitting there, browsing the news, and thinking: what if this could happen anywhere on the planet? What if suddenly all nations decided they couldn’t get along well enough?” In the end, the Guggenheim’s architectural spirals nursed his artistic abilities back into action. “If it had not been for the museum, I am not sure I would have got back to sculpture,” Vadim says, with some relief that he is working once more.

Kondakov was born in Bugulma, a small town in Tatarstan, an autonomous republic within Russia. The town was a centres of the republic’s oil industry and his family members have jobs in industries related to oil: Vadim’s father is a turner and his mother works in technical geology. He was always keen on becoming an artist, citing a psychedelic experience in childhood as formative. “I remember lying in bed at night and waiting for my eyes to adapt slowly to the dark,” Vadim remembers. “The ceiling turned white again, and for a split second I thought that I made the chandelier disappear!”

In Bugulma, there was little scope to get an artistic education. “When I was a teenager, the town started to fold in on itself: no jobs, no opportunities,” says Vadim. “I had to leave.” He first went to Kazan, the capital of Tatarstan and studied at the design college however, he felt that even the biggest city in the republic was still provincial, and in 2011 he moved to the State Stieglitz Academy for Arts and Industry (‘Mukha’), Saint-Petersburg’s prestigious higher education art college. At the time, a new generation of Mukha alumni was looking for ways to turn their academic studies into contemporary art. A number of young artists founded the Squat of the Unbowed (Skvot Nepokorennykh, named by the street on the outskirts of Saint-Petersburg where the artist-run studio space was located). Looking at their work, Kondakov started to feel a disconnect between the requirements of academic rigorousness and the work that was produced elsewhere.

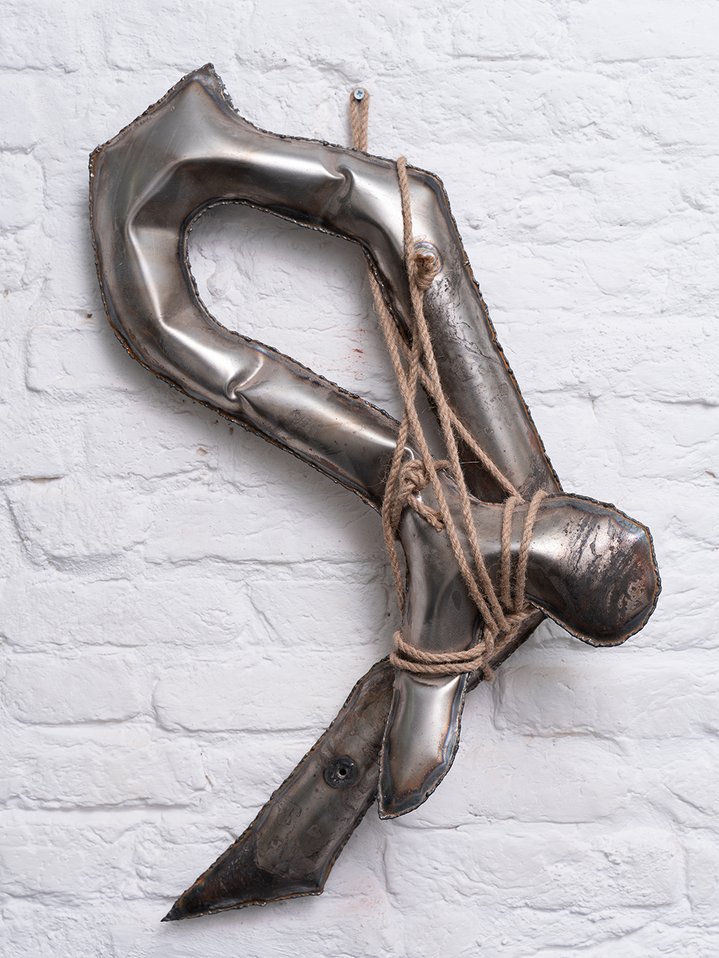

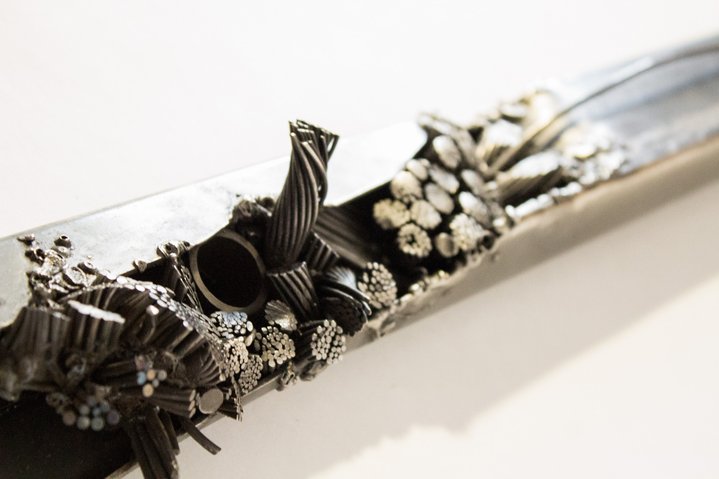

A fateful meeting set him on his path. Nikolay Sazhin, professor in the ironworks department at Mukha, was well-versed in Saint-Petersburg’s underground scene. Under his supervision, Kondakov turned to iron and steel, finding his own way of working. He took steel sheets, welded them together, and inflated them into structures that resembled organic matter even as they manifested their industrial nature. Vadim remembers encountering a discarded bust of Lenin in the courtyard of the college. “I looked inside, and there was an incredible space that had nothing to do with the image, a whole new universe,” the artist remembers. “I bought a camera and filmed the interior of the statue. It was like a horror movie!” The dynamic of inside-outside proved to be central for Kondakov going forward.

After a stint in Saint-Petersburg’s progressive art school Pro Arte, Kondakov started to hang out with Sever-7 (North 7), the city’s coolest band of young artists. He remembers a New Year party at Kunsthalle Nummer Sieben, the group’s basement art gallery, where people dressed up, created impromptu artworks, and pursued artistic freedoms with anarchist abandon. At that party, a friend jumped at him, wearing a bathrobe, and shot a blank from a fake revolver. Sharing that same spirit, Kondakov started showing his work with Sever-7. It was featured in the group’s important Moscow exhibition in 2021, when the Sever-7 built a total installation at the Ovcharenko gallery in Winzavod. The resulting exhibition, Marshes Your Way, did justice to Sever-7’s sarcastic brand of post-modern bricolage. “Progress is a historical costume party where Lucas Cranach the Elder drinks nectar while petting a white sable; Brueghel's blind men offer the latest vaccine, and the guests of the Salpêtrière clinic build an old money spaceship and sell NFTs,” wrote the group’s mouthpiece, Liza Tsikarishvili (b. 1988), in the show’s press-release. The space was full of wooden constructions, thick as a forest, with artists’ works attached to it at various heights. Kondakov showed both recent and older sculptures, providing a counterpoint of a somber Modernist sensibility to Sever-7’s carnivalesque and colourful aesthetic.

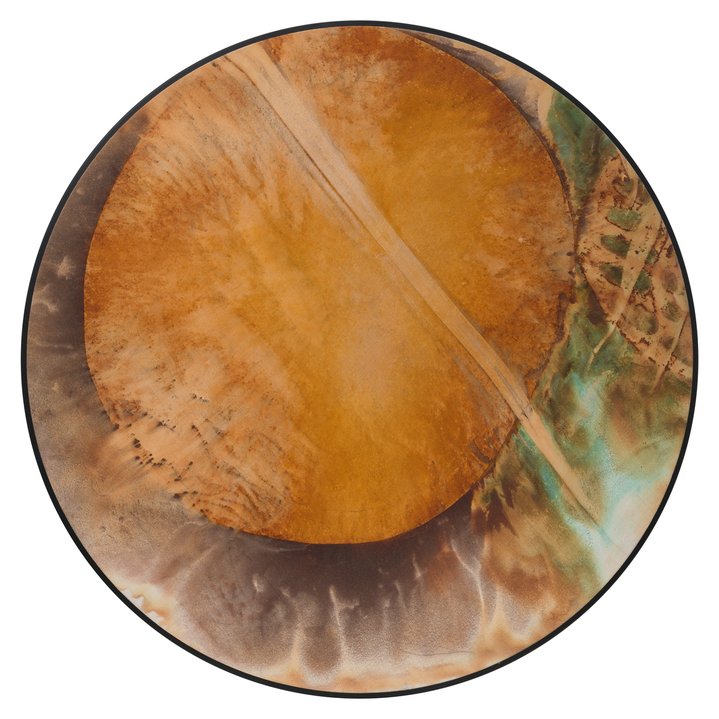

In New York, Kondakov has found a deeper understanding of steel’s internal logic, something that his Constructivist predecessors referred to as “the truth of the material.” Most of his material is found on the Staten Island beach which Kondakov combs for inspiration and texture. Political catastrophe has inspired Kondakov to move in a more social-conscious direction. “My abstract works drift towards the social,” he explains. “People want iron to behave in certain ways. They paint it to give it sheen, restore it to make it more useful and last longer. I am letting metal loose, so it can get a little rest”. He has begun to experiment with rust, oxidization and copper. Rust is “when metal is relaxed and at peace with itself” he says. And adds, “the form is secondary, I am interested in following the process”.