There Are No Dead Artists for Boris Matrosov

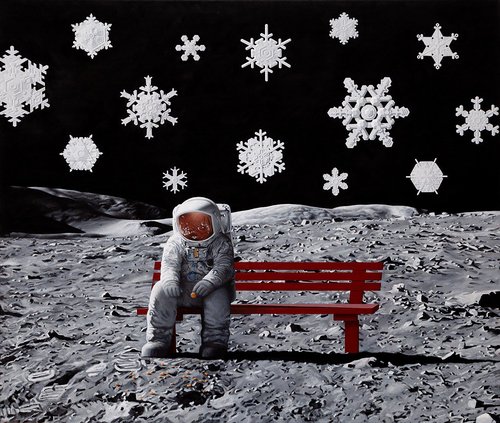

Boris Matrosov. From ‘Friend’s Landscapes’ series. Courtesy of Peresvetov Pereulok Gallery

A solo exhibition by Boris Matrosov, his first in almost a decade, has opened at the Peresvetov Pereulok gallery in Moscow. It is a surprising comeback for an artist who has remained on the fringes of the art scene for many years, even though one of his works has become an international landmark in the city of Perm.

The artistic career of Boris Matrosov (b. 1965) is anything but a ‘career’. It has developed through fits and starts, oscillating between periods of intense activity and long periods of silence, between wild performances and contemplative drawing sessions, between national fame and total obscurity. Matrosov is the only artist in Russia whose public artwork has become the symbol and mascot of a big city, a landmark revered by both locals and tourists, an achievement which did not lead to any more major public art commissions, and he has had very few solo exhibitions. The typical gallery lifecycle where an artist needs to come up with a new exhibition every year is not suited to Matrosov. “I panic when they rush me,” he confesses, believing instead that art should grow organically and not be produced as if on an assembly line. When talking about his past projects, he evokes a sense of things and circumstances “growing together”, as he calls it, reflecting on how sometimes they do, but that more often they do not.

Perhaps the whirlwind of creative activity in his youth exhausted his energy too early. In the years of perestroika, when unofficial art emerged from the underground, Matrosov and his former schoolmates Gia Abramishvili (b. 1966), Igor Zaydel (b. 1966), Konstantin Latyshev (b. 1966) and Andrey Yakhnin (b. 1966), together with an older friend Konstantin Zvezdochetov (b. 1958), founded the art group ‘Champions of the World’. Although the group only existed for two years, from 1986 to 1988 it left its mark on the Moscow art scene. The Champions became known for their ironic performances, a far cry from the carefully staged, esoteric actions of the Moscow Conceptualists. One of these was called ‘Grey Sea’where two members from the group, travelling separately, happened to visit the Black Sea in the south of Russia and the White Sea in the north. They brought back bottles of water from each and pouring them into a hole in the ground, and called it the ‘Grey Sea’. They participated in every group exhibition, created numerous works of art from household waste and disposable materials that were thrown away after the show, and never bothered with documentation. For them, the creative process seemed more important than the results. Very few works by the group have survived. Thirty years later, when Paquita Escofet Miro, French collector of Russian art, Evgenia Gershkovich a Russian art critic, and Olga Turchina an art historian decided to organise an exhibition of the group at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, it proved to be challenging to find original works. Strangely enough, the city exhibition hall where the group showed their short-lived creations is still in use today. And its young director, Galina Chernova, aware of its glorious history, approached Matrosov asking him to mount a solo exhibition there. It took him a year to complete it. As he shows me around on a gloomy December afternoon, the drawings are brightly lit, but the hall itself is shrouded in twilight, as if sinking into the shadows of the past.

When the group disbanded, Matrosov did not lose his taste for performance. In 1997, together with fellow artists Aleksey Kuznetsov and Alexander Petrelli, he founded a collective called ‘Deep Purple under Plywood’ a biting imitation of the real rock and roll band. The name is a play on the Russian word ‘fanera’, which means both plywood and, colloquially, pre-recorded music used by unscrupulous musicians during ‘live’ gigs: they came on stage with plywood guitars and lip-synced to recordings of Western hits blaring from loudspeakers. According to former attendees of such shows, the band fired up their audience as if they were real rock stars. Matrosov considered building a complete set of instruments for a symphony orchestra out of plywood, but never realised his idea. He says he reveres classical music too much to make fun of it.

Matrosov rose to sudden fame after he made a monumental sculpture from two metre high letters which formed the phrase ‘Happiness is not over the mountains’ for Art-Pole (which literally translates as "Art Field" in English), a public art festival organised by artist and gallerist Aidan Salakhova in an upmarket Moscow suburb in 2005. In 2009, the workwas brought to the Urals city of Perm by Marat Guelman (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities), then director of the Perm Museum of Contemporary Art. Guelman’s attempts to adorn the city with works by contemporary artists sparked controversy among the city’s art community. Many of the works he had chosen were heavily criticised and eventually taken down. However, the work by Matrosov, placed on one bank of the Kama River, was an instant success. It appeared on numerous postcards and souvenirs, and even in a Kanye West video. “It’s all because of the water behind it,” says Matrosov. “I don’t even know who decided to put it there. It just came together.” In 2018, local street artist Sad Face (Aleksey Ilkaev) vandalised the work, turning the word ‘Happiness’ into ‘Death’. The work was quickly restored.

Matrosov’s practice is diverse, if patchy, but the same approach to conceptual art is evident throughout: he always reduces each medium to its bare minimum – to a sign, almost to a sigh. Performances without documentation, concerts without instruments, text-based works with only a handful of words. His approach to painting which for decades has been his favourite medium is the same. The style of his paintings is reminiscent of early drawing apps from the 1990s likePaintbrush, although Matrosov claims he has never mastered art-related software and always sketches by hand. The colours are bright, the details few. They indicate rather than depict. “Even when we look at a realistic painting, we don’t just see what’s depicted, but something else behind it. That is the nature of art,” he says. His exhibition ‘Friend’s Landscapes’ is a typical – and yet not so typical – example of this approach.

Dedicated to a friend, the artist Danya Filippov, who died at a young age in the early 2000s, it is a dialogue with the deceased. The whole series was inspired by a collage by Filippov, a faded snapshot portrait of Matrosov framed by a photograph of a birch grove in early spring. Matrosov responds to this nostalgic image with a series of colourful, minimalist acrylic landscapes on paper. “Danya imagined me in this spring forest. And for me this series is like a conversation with him. As if we were looking at one another,” he explains. For him, there is no sadness or longing in these works, but rather a sense of connection. “There are no living and dead artists – all artists are alive, they can inspire someone else and the dialogue continues,” he says. But something strange, even ominous, disturbs the serene brightness of these landscapes. These intrusive, abstract forms look like signs or letters of an unknown alphabet – but, unusually for Matrosov, they mean nothing. For him, they represent the shattering reality around him. “It is as if I am trying to concentrate on something through these forms, but I cannot do it because they keep falling apart.”