The Semenikhins: Jacks of all trades

Chagall famously wrote that it was through being an artist that he became a man. It was his ultimate calling. Art-collecting and cultural philanthropy are social activities which can create influential legacies akin to great artists. The Semenikhins are two of the most active among Russia’s cultural elite. How is their legacy shaping up?

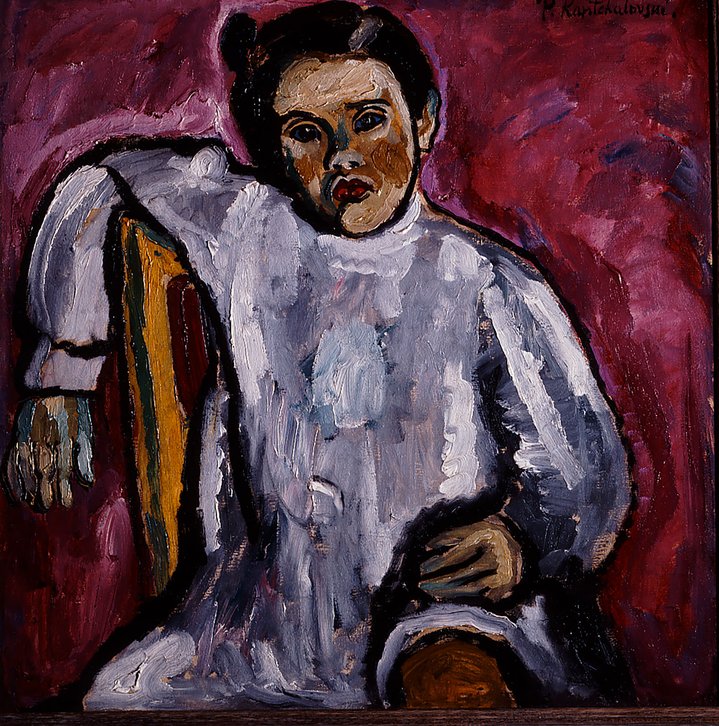

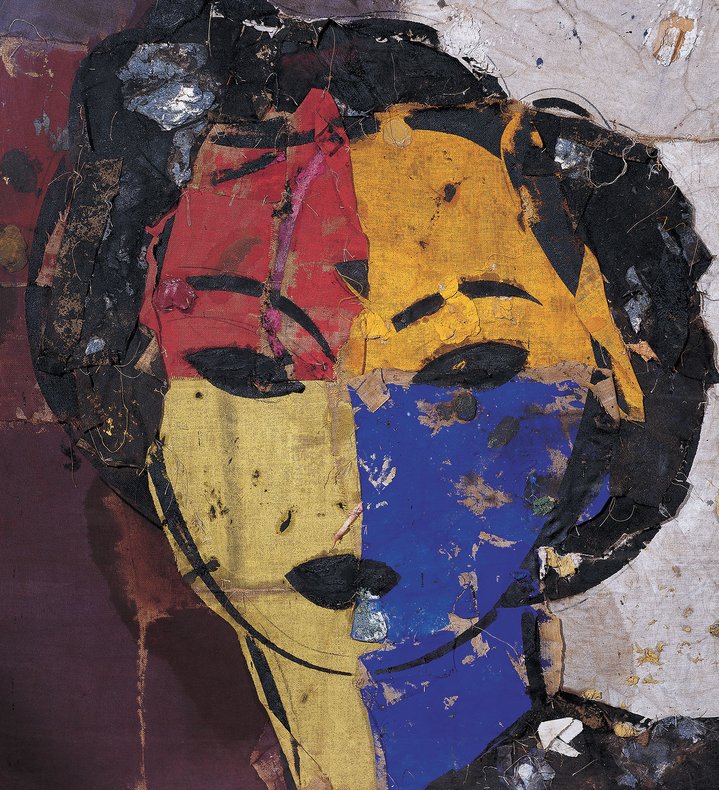

I first met Vladimir and Ekaterina Semenikhin back in 2004, barely a decade after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, just as Vladimir Putin won his second presidential term. It was then amid the fast social changes of those years that they came up with their first grand cultural project, an exhibition dedicated to the Russian modernist group ‘The Jack of Diamonds’. I recall as a young art expert wandering down the long exhibition spaces in semi-darkness excited by the primacy and colours of the expressive portraits with which I was at the time only vaguely familiar. With hindsight, I see what an achievement this was: it was a whole year before the Guggenheim’s ‘Russia!’ exhibition brought national art to the public’s attention in New York. The Semenikhins had drawn works from no less than 18 state regional museums across Russia, it was an unprecedented scale, the subject was new, not only for the Western public, but in Russia itself. The same exhibition with some additions was later shown at the Russian Museum in St Petersburg and in Moscow at the Tretyakov Gallery. Senior curator Irina Vakar revealed her frustration, saying that they had been trying for a long time to show the Jack of Diamonds in all their glory. These state museums were pipped at the post by a couple of art collectors, who were they?

Even today, a few decades down the line and many more firsts to add to the Monaco show, it is not easy to find this out. Despite having met them on several occasions, I decide to canvas some friends in the art world who are better placed to have a personal view. People do not tend to like talking about them, a reticence which is down to the cultural mores around these kind of extremely wealthy, well-connected personalities in post-Soviet Russia. Those that know the Semenikhins well are fiercely loyal and glow with a kind of unspoken appreciation. Perhaps this is unsurprising, as Ekaterina’s grandfather Aleksey Kosygin was one of the most enlightened Prime Ministers of the Soviet era. Their family exudes good education, manners and a social conscience. Vladimir, a civil engineering graduate, was born near Lake Baikal in the far East of Russia and got a taste for art through collecting post-cards as a child.

Ever since I worked on the Rostropovich-Vishnevskaya collection during my years at Sotheby’s, I have been fascinated by couples who collect art. I have the feeling that for the Semenikhins, art collecting is on some level an expression also of their mutual affection and respect for one another; as Vladimir comments ‘we rarely argue’. They only collect what they both like and it seems their tastes are very much in tune. Despite this equal footing, Ekaterina spends more time researching and working on possible acquisitions and looking for new works, partly because Vladimir is so busy with his construction business in Moscow.

Their collection initially evolved along lines which were quite conventional for Russian collectors who started out in the mid 1990s in the wake of perestroika. Their first interest was in Russian classical 18th and 19th century art, then they moved onto the early 20th century. This, they say is their greatest love. But, for the Semenikhins, it did not stop there. Even as early as the mid 2000s, they had already discovered contemporary art, both Soviet non-conformist art and then, subsequently, international contemporary art. This was at a time when you could count on the fingers of one hand the number of collectors of contemporary international art in Moscow, a city with a population of nearly 12 million.

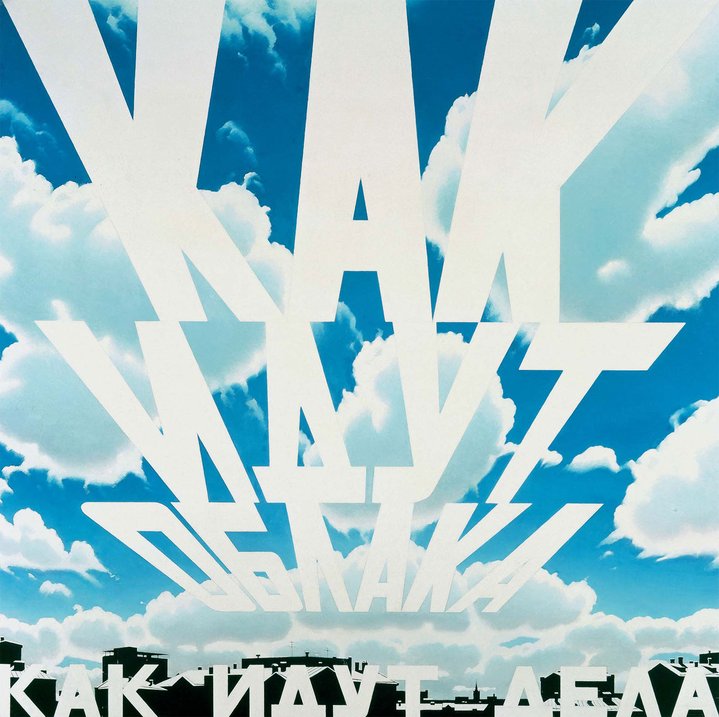

Vladimir speaks most passionately about Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), a close friend who showed them how to look at contemporary art and taught them how to appreciate paintings. Around this time, in 2007, they opened a dedicated space in the centre of Moscow, on Kuznetsky Most for the Ekaterina Foundation which they established, initially just to administer the ‘Monaco Jack of Diamonds’ show. Another first – at the time there were no other permanent non-profit private, yet public, cultural spaces in Russia. Its name ‘Ekaterina’ was Vladimir’s idea: it is more than an expression of appreciation for his wife; Ekaterina II (Catherine) was the greatest collector in Russian history, her name is synonymous with art patronage and “nice and familiar”.

How close do these two get to art royalty? Only time will judge, but I would include them on a short list. At their initiative, the first ever solo retrospective exhibition of Erik Bulatov was shown in Russia at Treyakov Gallery. Retrospective shows at the Foundation have been educational and pioneering in the field of contemporary Russian art. They have presented comprehensive, large scale historical surveys from the late 20th century period, such as ‘Reconstruction, 1990–2000’ and ‘Field of Action’, taking on the best Russian curators Elena Selina and Elena Kuprina-Lyakhovich, publishing catalogues which have become compulsory reading for any students of the subject. They have the vision to identify projects which have important cultural value, playing a part in the writing of Russian art history: “At a certain point of time in the life of a collector, there comes a moment when he or she needs to share ideas and their collection with other people, our exhibition space has fulfilled that need. You cannot always bring your ideas to people in the context of museum exhibitions, therefore the availability of your own exhibition space allows you to fill this gap.

Despite this on-going contribution to Russian contemporary cultural life, will it be for the activities of the Foundation that they will be remembered a century down the line and how will the Foundation and their own values embedded in it evolve? In Russia, perhaps like nowhere else, private patrons are shouldering some of the responsibilities of the state in tending the cultural landscape throughout the fast-changing seasons of our own times. There is a real burden. Yet, all around the world are examples of how private art collectors can contribute to all of us with some of the best state museums today, filled with treasures that once were collected privately. As collectors, the Semenikhins have long honed the sense of what belongs at home and what can be displayed best in an institutional setting; Ekaterina talks in Russian about “domashneye Kollektsionirovaniye”, (which literally translates as “home collecting”), as opposed to what they buy to be shown in a more public setting, in a large space.

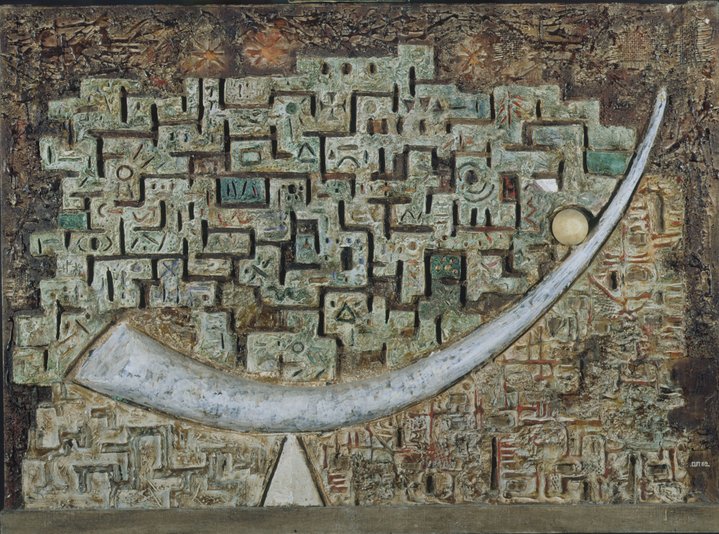

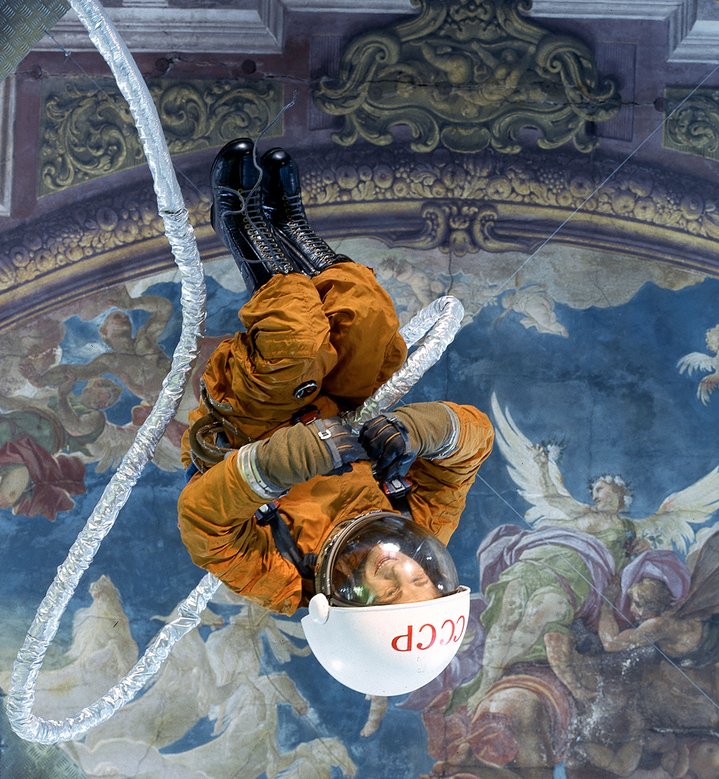

The collection includes work by James Rosenquist (1933–2017), Manolo Valdes (b. 1942), Claudio Bravo (1936–2011), Oleg Kulik (b.1961), Erik Bulatov (b.1933), Francisco Infante-Arana (b.1943), Dmitry Plavinsky (1937–2012) and, among less established artists, they mention Egor Koshelev (b.1980), although they are quick to say they do not have favourites. Add these to their collections of Classical Russian art, Russian modernist art, Russian ballet and theatre designs, Murano glass and it is clear just how wide their interests are, can a collection be too diverse? I ask what they think is the “overriding, distinguishing factor in your collection?” “We like beautiful works,” says Ekaterina, but she adds carefully, “we do not shy from complicated subjects.” It may seem old fashioned today to talk about beauty, but in spite of a century of innovations and art revolutions, it is an enduring quality we can all relate to.

The Semenikhins are not often seen at the countless art world events, soirees, openings, or fairs, which were a staple of the pre-pandemic art world. What might be interpreted by some as reclusiveness is probably more a reflection that they have all they need from their own close-knit family life and the demands of their Foundation, which I think lie at the heart of what seems to be an enviable private world. They love spending time with artists and, in the future, plan to concentrate more on supporting artist projects. Despite their desire to give of themselves to creative endeavours, their approach to buying contemporary art directly from artists is careful and considered, perhaps defensive: “It is important not to be led too much by your emotions from your encounter with the person, you need to separate the work from its creator.” As for their collecting legacy, I think at the moment they are still shapeshifting between being jacks of all trades, to masters of the contemporary world. I wonder what will endure to define the collection. Ekaterina concludes: “One of our main interests is to collect contemporary art. That is what we have arrived at in the end…” before adding, “but we are interested in so many movements, we are practically omnivores, if we can say that?”