The Scissors in Dashevsky’s Head

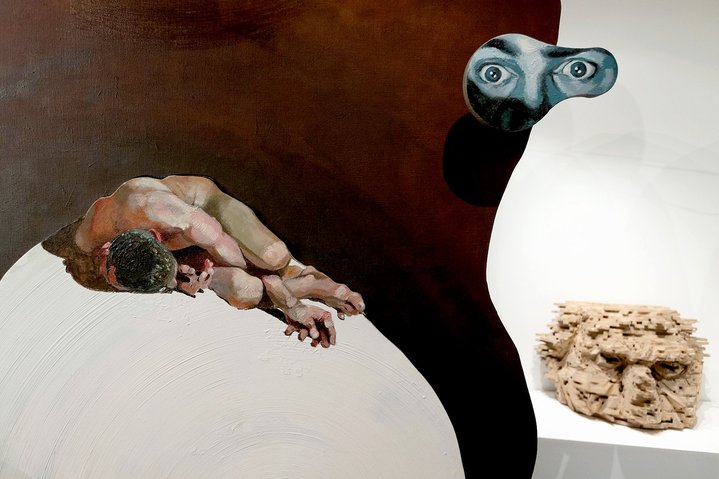

Alexander Dashevsky. Pavilion, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and the Triumph Gallery

Russian contemporary artists are between Scylla and Charybdis: harsh state censorship at home, and the critical art community abroad, which rejects any form of expression other than direct political action. However, in Alexander Dashevsky’s solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Moscow a transformation of censorship into self-reflection lies at the centre of his project.

In 1969 American psychologist Elizabeth Kübler-Ross published her ground-breaking study in which she identified the five stages of grief or loss. She set out to describe the experience of terminally ill patients, but her system was later adapted to the emotions experienced by people suffering any great loss. In Kübler-Ross theory there are five stages which follow in sequence: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. You could start at the bargaining stage and just sink into anger and denial with no way out. Everyone goes their own way, with an awareness of the path they have to follow.

Traditionally in art, artists have been responsible for the production of images. Among other things, images are an aspect of an individual memorialisation of memory. But state propaganda also works with people’s memories, channeling them into false patriotism and resentment. It is this difference between what is personal and what is manipulated in our visual expressions that Dashevsky (b. 1980) explores in his new exhibition.

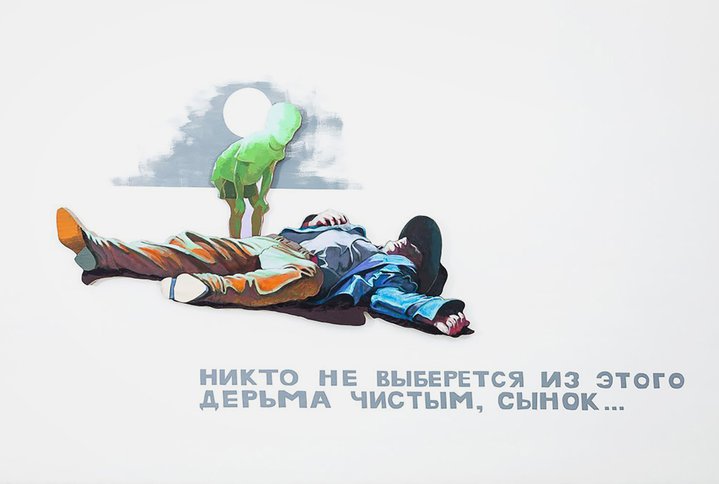

At first glance, his show looks rather traditional: there are paintings, graphic works, objects and texts from different years. But on closer inspection, all these pictorial components are part of a game which the visitor gets drawn into, where the real meaning is actually hidden in what is left out or omitted. One of Dashevsky's signature techniques is the use of monumental canvases, individual paintings combined like a mosaic. Some parts literally are lost or erased. Similiarly in the fictional author's texts by the artist fragments and words are missing. And there are spaces in the exhibition which have been left deliberately empty, as if some works have disappeared or have been excluded from the exhibition for an unexplained reason. Encountering these gaps, viewers might understand that they need to fill in the missing parts from their own experience and sense of personal responsibility. Criticising the artist is not an option. The goal of the exhibitionis partially hidden by a metaphor for self-censorship: a phrase in the German language ‘die Schere im Kopf haben’meaning literally ‘to have scissors in your head’ which is the title of the exhibition. For Russians, German is a language of commands and action requiring immediate reactions, unlike the Russian rock-n-roll approach ‘Change is what our hearts demand’, which, apart from romance, does not suggest any action at all.

Once a visitor becomes aware of the insidious game into which the artist has drawn him or her, one might ask the question why? What lies behind all this? Alexander Dashevsky was born in the Soviet Union and the city of Leningrad, but now lives and works in St Petersburg (Russia) although he has not changed his country or place of residence. As a child he was caught up in Gorbachev's Perestroika and through this tumultuous change had a liberal education including the study of three languages, art history, cultural studies and the history of religion. Then he studied economics and art history in two different universities.

"Art was the one thing I did where I just knew I wasn't wasting my time. But the art education system that existed in Russia at that time did not suit me at all. I studied at the Academy of Arts in Petersburg for four years and then left. There, the history of art ended with Van Gogh and Surrealism. There was no further information, I had to find it on my own. Art history and economics are two different ways of understanding the world. In economics, at the time, there was much more knowledge about the world. By now I was no longer interested in painting as a genre, a mode and a form of expression. At the same time, I have never stopped being interested in painting itself. Because the way it exists is more expansive and far from being fully developed. I like the experience of children when they start painting on a sheet of paper, and then the paint and drawing spills onto the floor, the walls, their bodies and fills everything around them. If you don't put in a frame of constraint, which the boundaries of the canvas give, the process becomes more interesting".

With a natural charisma, he took his painting ‘to the people’. He chose St Peterburg’s depressing ‘sleeping dormitories’for adventurous experiments in a project called ‘The Real Estate’ which showed approaches which later becameidyosyncratic. "I would go out to these sleeping dormitories, stand with my easel on a busy street and paint canvases. An audience would quickly gather around me. I saw a whole range of reactions from extreme aggression to declarations of love. After a while I no longer observed nature, what mattered was the social drive emerging around me. The police took me in for questioning several times. I annoyed them because they could not understand what I was doing and it was deemed to be an informal protest. But also with people gathering around me, that was seen as suspicious. Looking back, it is clear that the appearance of an artist was judged as something wrong and unofficial, a kind of solitary picket”.

Indeed, painting was considered the most worthy genre in Russia until the early 1990s, when contemporary art institutionsemerged. Dashevsky’s first exhibitions were not connected with existing state institutions, but to the self-organisation of artists. In St. Petersburg, such practices were quite developed, and one significant exhibition venue in the 1990s was the Mitki - VKhUTEMAS gallery, opened by artists from the eponymous group. They then came up with the project ‘Society of Painting and Drawing Lovers’, which, with a postmodernist squint, encouraged lovers of painting to do what they wanted - travel and indulging in plein air - while the emphasis in these trips constantly shifted to performance based on social communication. It is from this that Dashevsky built up his own practice.

The largest of his composites canvases stretches more than three square metres and consists of 30 individual canvases of different sizes. It depicts a huge dormitory from the Kupchino district. The typical building occupys the entire surface of the canvas, its geometric patterns repeated, but each fragment unique. In this way the utopian project of ‘social housing’ in the 20th century, which created waves all over the world, reached its finale in Russia, where the bright idea of utopia transformed itself into depression. And, of course, this metaphor is not just about architecture. When working on it the artist recalls: "I had the strong feeling I was discovering a whole universe that no one had dealt with, or I was making visible what was invisible. The locals couldn't understand what I found so beautiful to paint there. They actually hated the place they lived in. By 1995 it seemed to everyone that the Soviet past had been firmly forgotten and that this social project had disappeared from the discursive sphere. But when I talked to people living on the outskirts of the city, I sensed that this scar would still manifest itself in the future in the form of resentment. And I wanted to manifest that and make it visible through my art”.

In later projects, has has built up this reference to social practice through images with remarkable consistency. ‘Cells’ (2008) is a line of small canvases in the form of letterboxes. It is a conceptualist project about the residual modernist radiation remaining in everyday things. ‘Swimming Pool’ (2009) is an image of the future and the past through thisconcrete, socialist urbanist idea that has survived both total neglect and renovation. ‘Rear View Mirror’ (2008) is a road movie which looks back at the recent shared past of the former Soviet republics which Dashevsky created after a trip to Lithuania. ‘Partial Losses/Moderate Positive Dynamics’ (2013) brings together terms from art restoration and medicine into a single field; it is a project about the revival of the Soviet Empire. ‘The Fallen and the Fallen Out’ (2016) is about depression, mass ‘friendocide’ (a half-jocular term for severing social and social media ties) and falling out after the annexation of Crimea.

"The picture is a surface similar to a contemporary TV screen, and anything that looks like a TV today is exceptionallyidiosyncratic. I continue to live and work in Russia because St Petersburg is my hometown and it gives me energy and meaning. I can only think about emigrating if I am banned from my profession. Working as an artist is my way of living and thinking. Without that there is no way. Of course, it is impossible to do an exhibition today without reflecting on current events. I am preparing a show, investing my efforts and money into it, but I just do not know if it can even open", Dashevsky reflects a few days before the opening. Yet, the opening went by without a hitch. It seems that he scissors in the artist’s own head are functioning well.

Alexander Dashevsky. Die Schere im Kopf

Moscow, Russia

27 January – 19 March, 2023