The Refined Asceticism of Irina Zatulovskaya

Portrait of Irina Zatolovskaya. Courtesy of the artist

Painter Irina Zatulovskaya is well-known for her use of unconventional materials. She has just unveiled a solo exhibition at the Totibadze gallery in Moscow, while a bigger institutional show will follow at Moscow Museum of Modern Art in 2024.

Irina Zatulovskaya (b. 1954) is an artist’s artist. For the last two decades, she has fastidiously worked in a similar vein, producing figurative works known for their simplicity in which she often uses a very limited set of paints for one work – no more than four - taking found objects as her base and painting directly onto them. "It's an aspiration to asceticism," the artist emphasises.

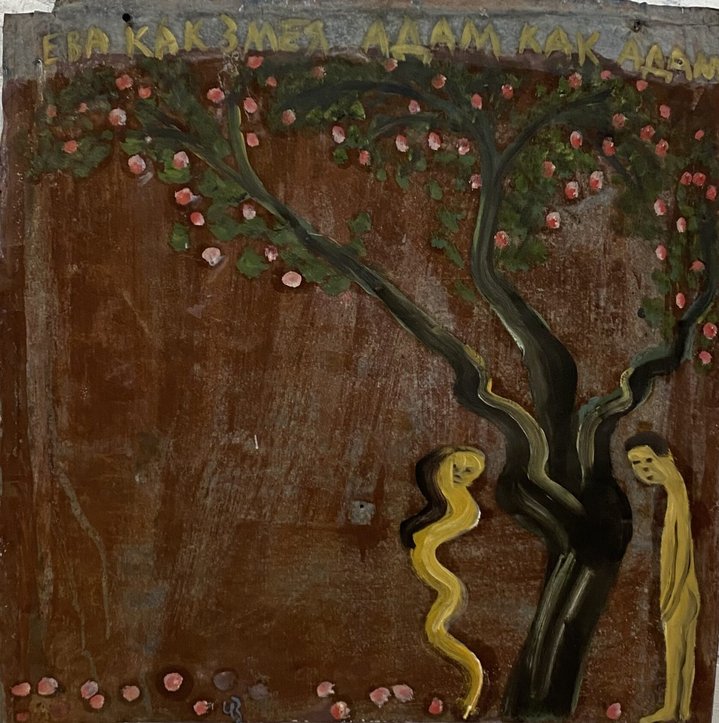

Rusted sheets of tin, old, weathered boards, pieces of plywood, antique cupboard doors...anything that might have rotted away in a rubbish dump, she revives by painting on it and at the same time drawing attention to the object. You could call her line of work pictorial archaeology or the reconstruction of the past in oil. It is a lyrical dialogue with the object and it seems that history itself enters into conversation with the viewer. Symbolists might say she reveals the souls of her found objects. Novalis would be better suited to characterise her occupation than Clement Greenberg, and Ralph Waldo Emerson more than Susan Sontag. However, Zatulovskaya herself believes that "that's not the point: many artists use many different bases, but that's not the main thing at all".

Her exhibitions have always attracted connoisseurs from the refined art world. At the opening of her new project at Winzavod in Moscow, Sergei Shutov (b. 1955), a well-established artist, told me about the simple feelings of joy he experienced a year and a half ago when standing in front of Zatulovskaya's works at the Pushkin Museum. One of the objects in the exhibition at that time were mummies of brushes, i.e. brushes bandaged into the canvas. These objects were a reminder of the daily labour of a painter who constantly has to wipe his or her tools, and at the same time they read like a requiem for painting, the art form to which Irina has dedicated her life for more than half a century.

Her solo exhibition in one of Russia's major museums opened at the bitter end of February 2022, becoming one of the first art events to take place in a museum after Russian troops entered Ukraine. Its theme, ‘Escape to Egypt’, had been dictated by an official agenda: ‘The Year of Humanitarian Cooperation between Russia and Egypt’. However, against the backdrop of the events taking place, even the title itself - conceived long before – suddenly seemed topical, like the theme of the Exodus, now relevant to Russian culture itself. "I would like to do an ‘antique’ project, it would make sense as I do a lot of painting on clay shards like antique ones," she adds.

Fayum portraiture has long been a big source of inspiration for Zatulovskaya. The flatness and small size, the intensity of line and the density of each stroke, a pared back use of colours and rich symbolism are all traits that can be found in her works. Other sources such as her interest in early icons, Russian folk painting, and Russian lubok she shares in common with Russian modernist artists Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964). In this Zatulovskaya is in some way aligned with this figurative lineage in the avant-garde, and on some level I think her painting is to some extent re-enacts the line of development of Russian art, which, having flared up brightly at the beginning of the 20thcentury then transformed into something completely different such as the straightforward agitprop or the mock folklore of St.Petersburg’s Mit’ki group. ‘Easter and Death with a Scythe’, a work Zatulovskaya has just completed, depicts a clash of two figures: a girl in red and death with a scythe under a red sun, painted on a wooden plank once cut by a village carpenter and roughly worked with an axe, just like the backs of icon boards used to be worked.

For Zatulovskaya it was a long path to this kind of painting. The artist's works of the seventies and early eighties are in the idiom of ‘quiet’ realism: self-absorbed paintings, which often explore the feminine. Particularly noteworthy are her self-portraits, such as her 1977 ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman’, in the collection of the Novokuznetsk Art Museum, which is an image of a woman in a mirror decorated with late-Soviet attributes of femininity: a pretty plate on the wall, a bouquet of flowers and a high-heeled shoe on a shelf. These kinds of works continue to trace the course of the post-avant-garde of the 1930s which Zatulovskaya learnt about through her teachers, graduates of Vkhutemas school. Then, in the early nineties her artistic style underwent a dramatic change. At the current exhibition at the Totibadze Gallery, there is a self-portrait she painted earlier this year of herself in her youth ‘Girl with a Burdock’. She has depicted herself in a pectoral view, holding a huge green leaf above her head, executed in a sparing manner, reminiscent of both the composition and attributes of a Fayum portrait.

For its imagery, Zatulovskaya’s work is close to an icon. But it is neither a Byzantine icon nor a salon of religious production. Her suggestive images achieve the maximum of expressiveness using just the minimum of means. The description of such works is always more verbose than the works themselves. Her 2023 ‘White Top, Black Bottom’ is a picture painted on a moulding, where a human figure is inscribed in a rhombus, carved once with a carpenter's tool, and instead of a head, the character has serrations and slits in a thick board left by the carpenter– natural defects in the material. The work itself reads like an average portrait of an office worker with a hole instead of a skull.

Irina Zatulovskaya has never hankered after the mainstream, either as an official artist or in non-conformist underground circles. As a third-generation artist, she followed a typical path for people of her circle and epoch, first art school at Krasnaya Presnya, then the Polygraphic Institute, finally the Moscow Union of Artists. Her mother, Raisa Zatulovskaya (1924–2015), was a still-life painter; her grandfather, Sergei Mikhailov (1905–1985), was one of the founders of the Moscow Secondary School of Art, the institution from which most of the capital's famous post-war artists emerged: such as socialist realist Gzely Korzhev (1925–2012) and the Moscow conceptualist Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023). All of them were once students of Irina's grandfather. This could have been the end of her artistic biography: belonging to the clan from birth, there was no need to go beyond the usual limits of craft, but Zatulovskaya went further than the average Soviet painter. Today her works can be found in museums all over Russia, in Vologda, Krasnodar, Krasnoyarsk, Novosibirsk, Rostov, Ryazan, Tula to name just a few.

Her art has not been affected by any of the dominant trends over the past few decades, such as photorealism, conceptualism or even performance or new media art. One way for young Soviet artists in the sixties and seventies to stand out was to look at the West to absorb the latest artistic trends there through the few available books and magazines without the possibility of direct acquaintance with the originals. Another way was through conscious retrospectivism and museum intoxication, from turning to Quattrocento art, as in the case of Moscow artistic guru Dmitry Zhilinsky (1927–2015), to a fascination with Tomsk pisanitsa – Siberian rock paintings – like Krasnoyarsk patriarch Andrei Pozdeev (1926–1998). Irina Zatulovskaya is a bright example of the second trend and it is through her spontaneous approach that she has finally found her roots. The earliest surviving example of easel painting is a Fayum portrait.

"Pirosmani did not study at an institute and knew these laws [of beauty] better than we do," Irina Zatulovskaya once said in one of her interviews. And this reveals another secret of her painting: it is in the ability to never become an adult.