The man behind the myths

Artist Leonid Tishkov has written an autobiographical novel where fiction and reality intertwine in a dreamlike way. Yet, you don’t have to know Russian to immerse yourself in the surreal universe created by the most prolific myth-maker of Russian art.

Leonid Tishkov (b. 1953) has always been crossing borders between genres, mediums, cultures and languages with incredible ease. The title of the artist’s new book, ‘Look Homeward’, is an obvious reference to the classic 1930s American novel by Thomas Wolfe, ‘Look Homeward, Angel.’ “Wolfe wrote about a small town in America, where he was born and I am writing about my own hometown lost in the Urals mountains. But, in fact, the title of my book is an homage to John Milton: Wolfe borrowed this line from his poem, which William Blake also liked,” Tishkov explained during our Zoom interview.

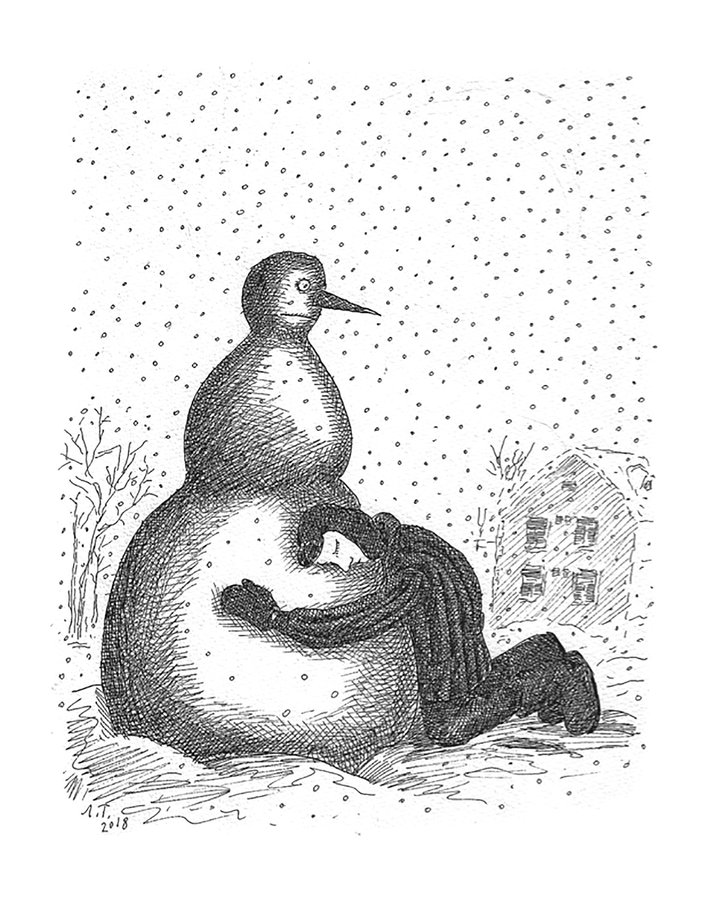

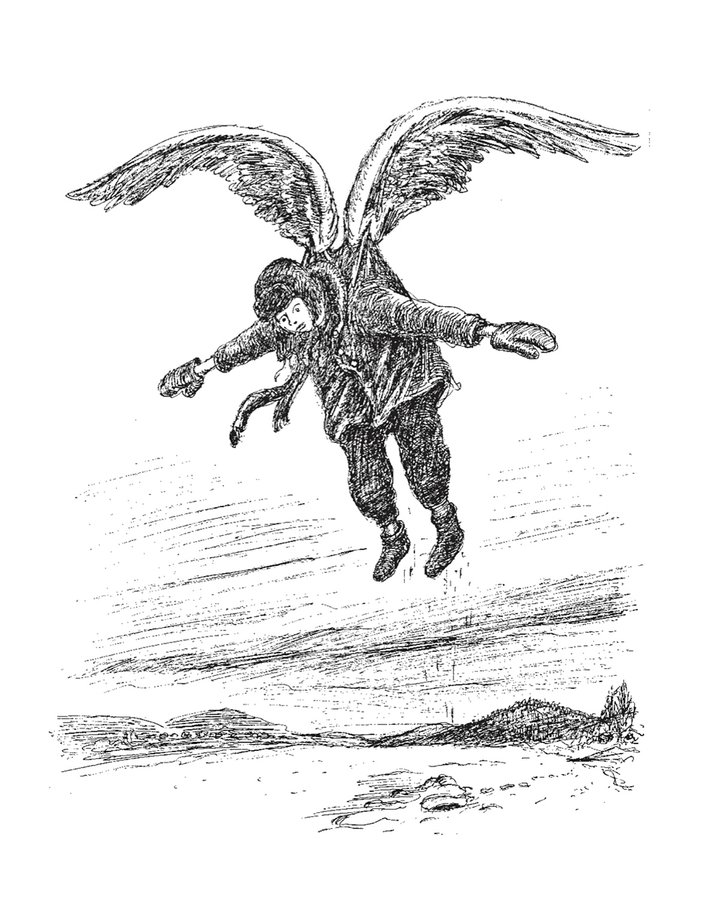

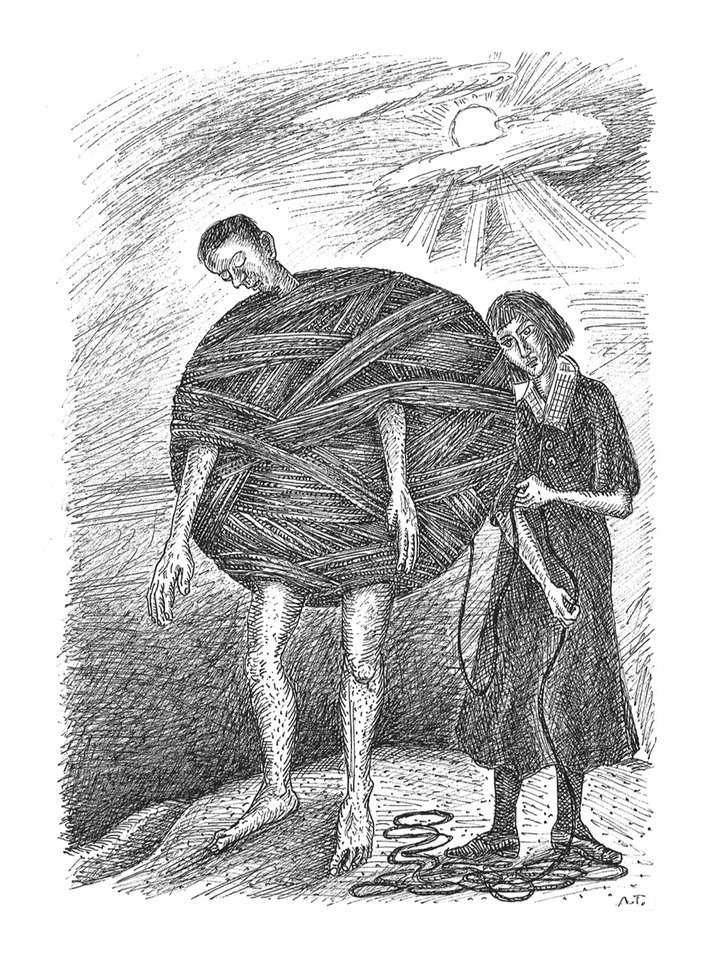

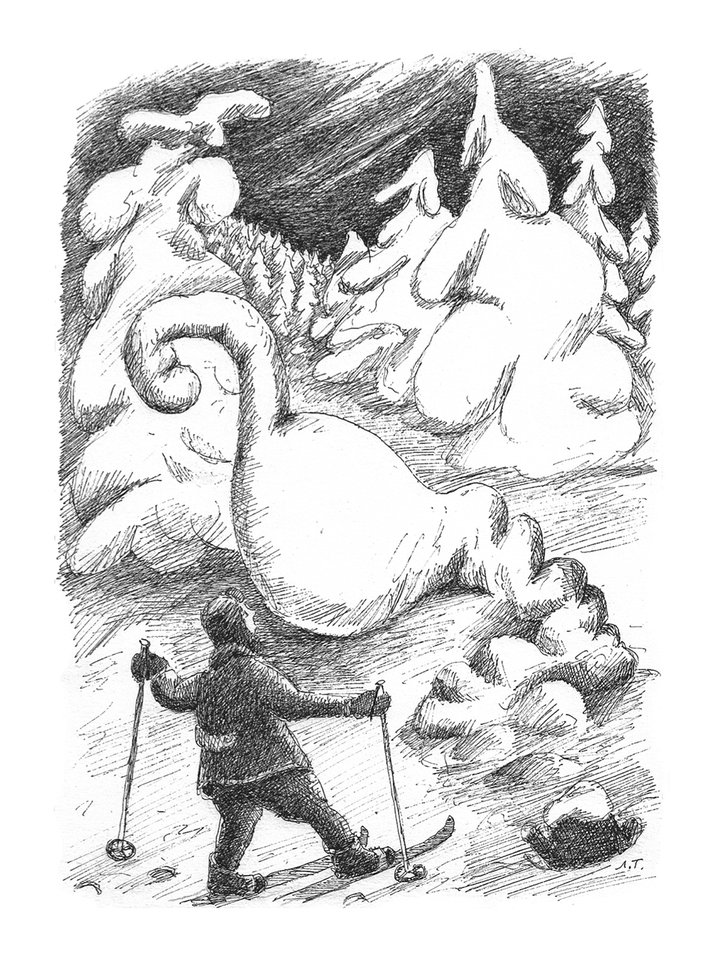

This is a typical Tishkov palimpsest. In his work, multiple layers of meanings and memories always overlap in unexpected ways. The novel, released by the Moscow’s NLO publishing house and illustrated by Tishkov himself, recounts a fictional version of his childhood. It is populated by real people, the author’s relatives and neighbours, but also by surreal creatures stemming from his various artistic projects.

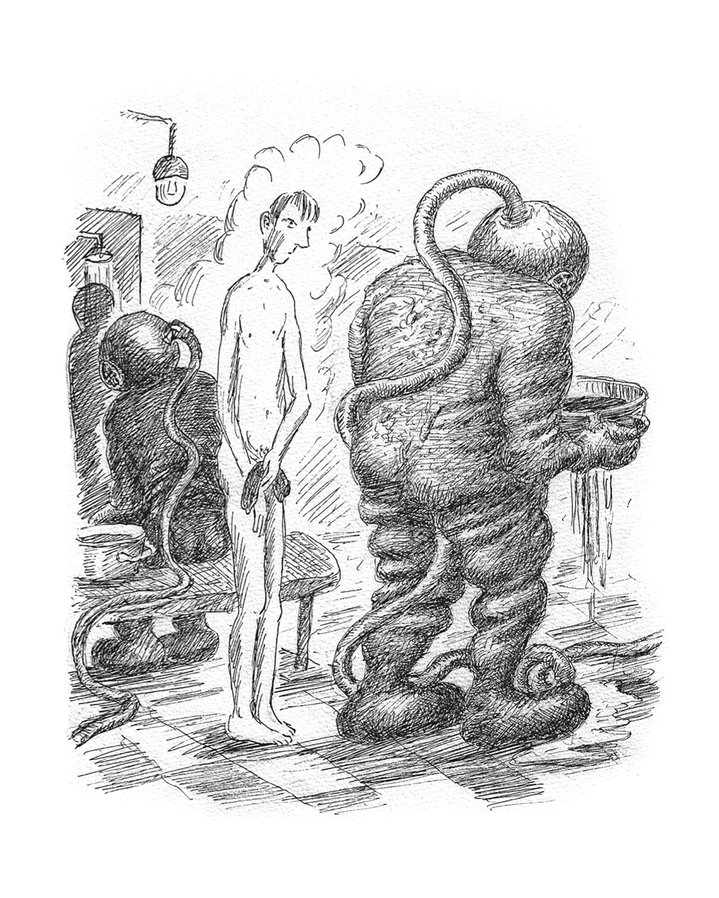

Trained as a doctor, Tishkov never enrolled into any art academy. He very early began a successful career as a newspaper cartoonist while still an undergraduate medical student. It ended abruptly when he sent a caricature to a contest in West Berlin. Tishkov was from that moment excluded from the state-controlled Soviet press. In the 1980s, he got acquainted with the Moscow Conceptualists who recognized in him a kindred spirit. Like them, he adored the album genre. “I have always enjoyed telling stories. For me, a single drawing is simply not enough. I need to make a whole series of them,” he says. He copiously filled albums and artist’s books with comics-like stories about mythical creatures, deep sea divers, mischievous “dabloids”, who looked like red human feet with tiny heads, walking stomachs and even a community of people living in elephants’ trunks. All these convoluted narratives about inhuman races had a common, surprisingly human touch, a curious mix of absurd wit, poetry and inner sadness.

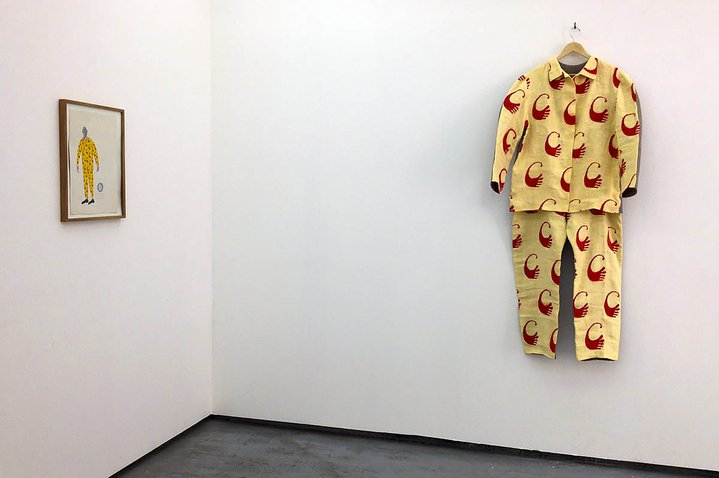

“For me, a story always starts as a text with illustrations,” Tishkov says. Later it can evolve into textile works, bronze sculptures, light objects, paintings, installations, videos and even theatre performances. Such opportunities began to open in the 1990s. After the fall of the Soviet empire, underground art was finally recognized both in and outside Russia.

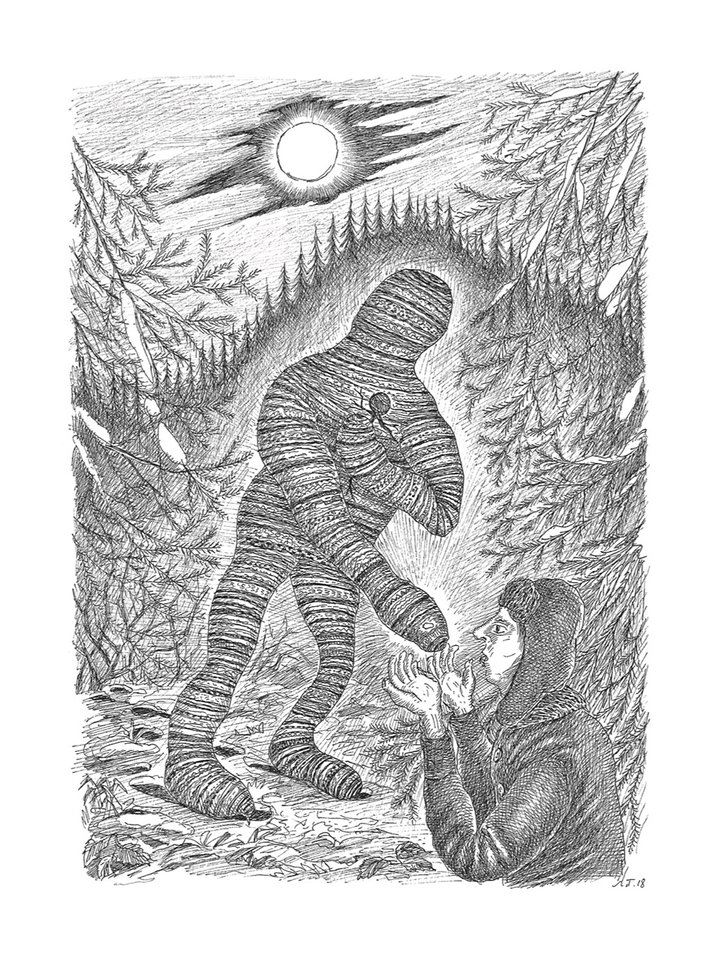

“For me, as a conceptual artist, the medium is not as important as the message,” Tishkov explains.“Yet when I use any materials or found objects, I pull all the scraps and bits of meaning out of them. Old rugs, torn clothes, used household stuff. For me everything is a text.” He is almost obsessed with things bearing traces of his own family history. “Sometimes it gets absurd,” he admits. “Once I needed a window for an installation and I travelled 200 kms to pull out a window from an old house I owned in the countryside”. His most heart-piercing work ‘Viazanik’ (‘Knitling’), is an overall designed by Tishkov and knitted by his 85-year-old mother using scraps of her deceased relatives’ clothes.

Tishkov is not as fascinated with words and wordplay as the Moscow Conceptualists. “Poetry is a universal thing. It is above language and nationality,” he says. His most poetic on-going project ‘The Private Moon’ stems from his own childhood in a lakeside town in the mountains, and nevertheless resonates with viewers in different parts of the world. “I keep different versions of this installation in America, New Zealand, Europe and Asia. That makes the logistics so much easier: no fuss with the customs,” the artist explains.

The magic of the Moon rekindled once again in his latest project in Japan, part of the Ichihara Art x Mix Triennial. Tishkov planned to adorn seven railway stations with light installations dedicated to celestial bodies. “Train passengers would feel like astronauts travelling to the Moon.” The Triennial was however postponed until 2021, due to the coronavirus pandemic. But the artist, confined to his Moscow apartment, does not rage against the lockdown. It’s the hypocrisy of the art world that bothers him most. “All these art centres, museums and galleries are so worried about themselves and their own future, but they should think more about the artists, most of whom live in penury in Russia. Support them, hand out grants or buy their works. After all, art institutions cannot exist without artists.”

During the lockdown, Tishkov launched a new project together with a Moscow printing workshop Piranesi Lab. He is going to publish some of his albums from the early 2000s as a series of limited edition prints. “Art should be affordable for all people, not only for oligarchs. It should hang on the walls of teachers, factory workers, software engineers, retired people,” he believes. “Art is not about the market and money. It is about ethics, fantasy and the human condition. For me art is first and foremost a dialogue with people. If their hearts respond to it, it’s much more important than any sale.”