The diplomacy of art

There generations. Tatiana Kolodzei, her daughter Natalia and granddaughter Anna.

Tatiana Kolodzei was born in Sofia in 1947, living in Moscow since 1948, she moved to the United States during perestroika. Who is this grand dame behind the unstoppable Kolodzei matriarchy?

With the most cursory read into the details of her life, you can almost place Tatiana Kolodzei, Russian art collector and co-founder of the Kolodzei Art Foundation, through the company she has kept over many years. The artists, the collectors, Soviet “royalty”, aristocrats and American business people: Chudnovsky, Shekin-Krotova, Dodge, Sherbatow and so on. Yet, she defies expectation, she is different, she has distinguished herself against the odds. As a female art collector during the late Soviet era, she was a lone figure without parallel for the default voice of the Russian art underground was resoundingly male.

There is one person in particular who helped her to forge her path in the art world during her early adult years, Soviet mega collector George Costakis. As a child, she talks of being ferried from one music or dance class to the next as part of that great Soviet/Russian education (my Russian friends today are among the most tigermomish I know) and it was not until she first entered Costakis’ apartment that she had a sense of being in the right place at the right time. Like when the fractured worlds of a teenager suddenly converge to bring about a sense of growing identity and selfhood. For some, this takes decades or never happens, for Tatiana at the tender age of seventeen, she found her life’s metier. That “becoming” turned into a kind of continuous thread, which still weaves today down the generations, with her work continuing through her daughter Natalia Kolodzei - and even her granddaughter Anna.

Kolodzei is a Polish name which unusually does not decline in the Russian language in the feminine form, as it is considered a word of foreign origin. The Kolodzeis are a rare dynasty. Art dynasties are the exception to the rule, as children of collectors often rebel against their parents’ obsessions for art or their tastes are radically different. The Kolodzei sphere of interest remains steadfastly focussed on non-conformist and Russian contemporary art. Through the family’s US based public foundation, which was set up in 1991 in memory of her father Alexander Kolodzei, known by insiders for its logo inspired by Lilya Brik’s revolutionary call for books to educate the masses, it is a charitable enterprise to raise awareness of Russian post-war underground art, more a mission than a collection today.

All of the Kolodzei legacy, in many ways, has survived against the odds. Tatiana’s beginning was beset with family tragedy: her father who had fought for Russia on the front during the Second World War was executed by Stalin during a purge targeting those who had been abroad as being potential spies. She is still not sure who is buried in his grave in Moscow. Born in Sofia, Bulgaria, she grew up in Moscow. Her mother passed away when Kolodzei was in her 30s.

“The word, ‘abstraction’, you were not even allowed to say it out loud,” she says of the Soviet times she lived through, before she and her daughter eventually moved to the USA during perestroika. It is hardly an exaggeration; it is easy to forget how crazy it all was. The Bulldozer exhibition in 1974 has gone down in history as one of the most fraught events between the artists of the underground and Soviet authorities, when art works were physically destroyed. Undeterred, before the dust had even settled, together with Talochkin, the following year, Tatiana Kolodzei organised an exhibition at the House of Culture at the VDNKh in Moscow for underground artists, in part to remember what had happened. It was not only the background which was challenging: it was the height of summer, during a heatwave and they were not allowed to open the windows during the set up. There were countless interferences by the authorities and set backs until the exhibition finally did open, in the end just one day late. It was during this time that Tatiana Kolodzei also introduced American super collector, the late Norton Dodge, to the underground circles and, thus, sparked off one of the most important collections of non-conformist art in the world.

After she moved to the USA, the cultural events and exhibitions have continued until now, even in her mid 70s, as she says of her days: “My diary depends on the art projects that I organise together with Natalia my daughter.” In the beginning, it was about promoting Russian contemporary art abroad, but quickly they also recognised the need to promote this art within Russia itself, where it had been long destined for obscurity and where art education needed to be reformed in the wake of perestroika. One of the most critically acclaimed exhibitions among the dozen or so they have organised since the 2000s, both in Russia and the West, was the first ever retrospective of the painter Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013) at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

Besides touring and sending paintings from the collection on exhibition around the world in group and mixed shows, they advise and support around two hundred US based, European and Russian collectors, who are interested in Russian contemporary art. They have collaborated on a curatorial and educational legacy project with the Zimmerli Art Museum, in which they have carried out over eighty interviews with artists from Moscow and St. Petersburg, as well as Russian artists living in the USA, which were included in Norton Dodge’s collection. It is something of a historical archive.

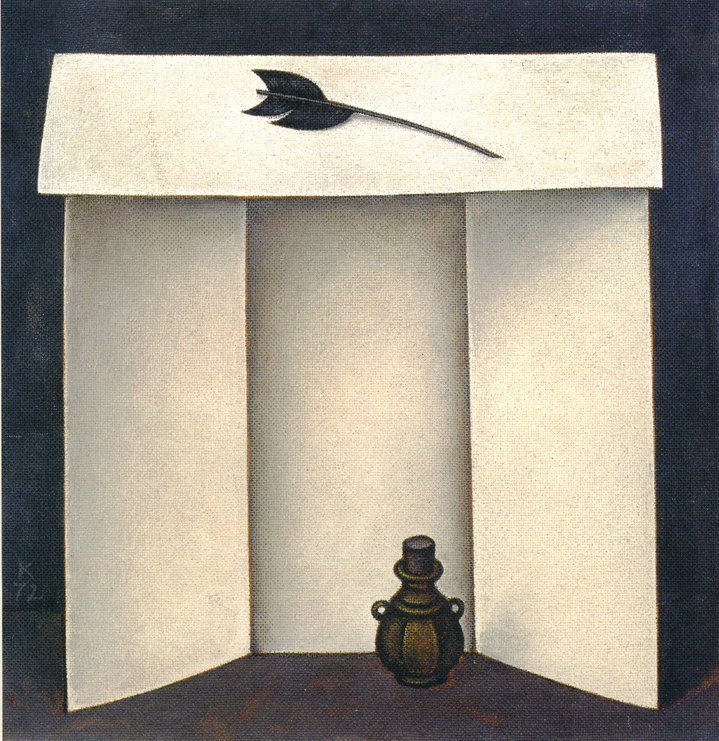

As for their art collection, it has never been about buying and selling, cleaning out the old for the new, as many collectors do. “We have never sold anything,” says Tatiana Kolodzei. It is a collection which is still growing, now numbering around 7,000 works. The core includes paintings, sculpture and graphics by classic underground Soviet artists, such as Ilya Kabakov (b.1933), Erik Bulatov (b.1933), Eduard Steinberg (1937–2012), Dmitri Plavinsky (1937–2012), Anatoly Zverev (1931–1986), Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016) and Ernst Neizvestny (1925–2016). She mentions historical works such as, a still life by painter Dmitry Krasnopevtsev (1925–1995), which she says was shown in the apartment of Svyatoslav Richter in the early 1960s. Her first acquisition was a painting by Boris Kozlov (1937–1999), which she was given as a gift by the artist when she married Leonid Talochkin in 1967 (divorced in 1969). In 1974,artists gave her gifts for the birth of her daughter Natalia, simply because they did not have anything else. For two decades, the collection was just shown to friends and family, there was no public interest. They lived in a communal apartment, the art acquisitions growing exponentially like the fairy tale of the magic cooking pot, you can imagine it literally taking over not only her own living quarters, multiplying, lying in piles under the bed, but perhaps you would open a kitchen cupboard to find a piece of art stuffed in there? The art collecting was all absorbing; she was happy despite the deprivations of the late Soviet period. “I did not drink coffee for 20 years, I just did not have the time to go out and look for it.”

The Moscow art world is notoriously tough territory, legendary for its internal divisions and there is a lot of ideological infighting. Tatiana Kolodzei always preferred to seek out what she calls artistic personalities and individual talent irrespective of the direction or movement they espoused, creating a diverse collection more representative of an era rather than one movement. When it comes to an art collection, this more intuitive, subjective approach can be both a strength and weakness, in the end, it is a personal vision. The collection continues to grow today, most recently they have focused on acquiring and promoting the work of female Russian artists and are exploring the crosscurrents between art and technology. With Tatiana’s granddaughter Anna already posting Anna Kolodzei Days of Art videos on You Tube, it seems that this matriarchal silver fox’s legacy is far from over.