The Art of Balance: Nemkova’s Sculptural Dialogues

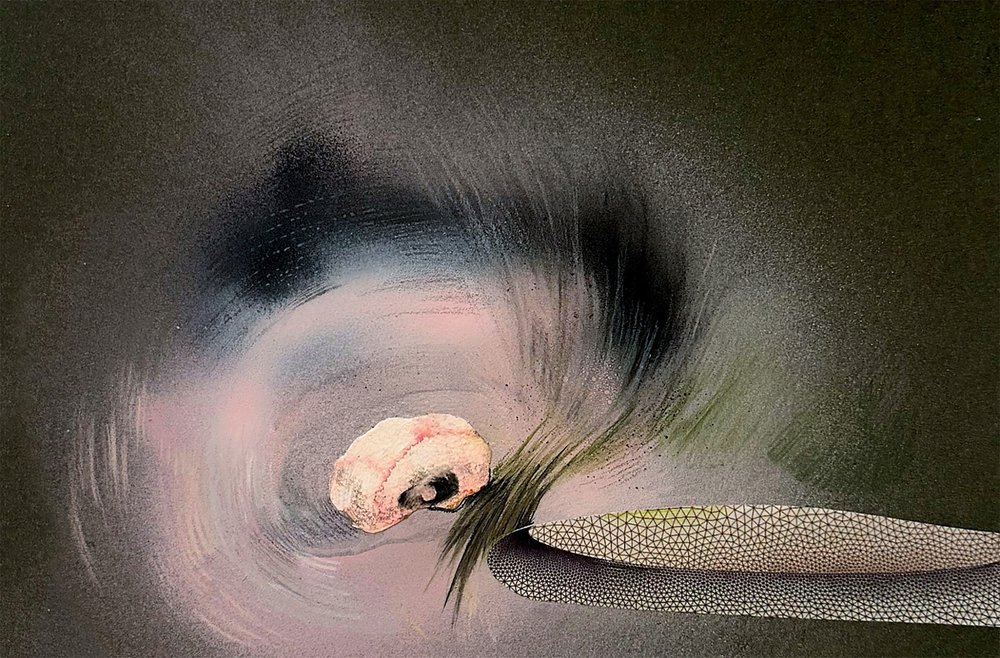

Elena Nemkova. Brain Factory. From the series 'Brain Factory and Landscapes'. Courtesy of the artist

Elena Nemkova’s artistic practice is a dialogue between creator and material, where patience and intuition guide the process. For her, art is not about control but about listening and allowing each work to evolve naturally until it reveals its own identity. At her solo exhibition Broken Instincts, now on view at Spazio C.O.S.M.O. an artist-run space in Milan, sculptures resist immediate revelation, mirroring her belief that art like love demands patience, discovery, and an ongoing dialogue with matter.

“Making art means immersing oneself in the essence of the material, engaging in a dialogue that is not about imposing one's will but about a mutual exchange of listening and respect. This process closely resembles dressage, the equestrian discipline where rider and horse perform predetermined figures moving in harmony resulting from deep understanding. Here, training is never about force; instead, it relies on a delicate balance — guiding while also responding to the horse’s subtle signals. Too much rigidity leads to resistance, while complete surrender results in a loss of control. Art follows the same principle. At its core, the creative act is never a solitary experience but a continuous unfolding within and through others”. In her own words, Elena Nemkova (b. 1974) tries to define what it means for her to create as an artist.

Born in Tajikistan to a Russian mother and a father of Finnish descent, Elena Nemkova grew up in St. Petersburg and has lived in Milan for the past twenty-five years. She admits, she has never felt fully rooted anywhere. This perpetual state of being a “foreigner everywhere” has profoundly shaped her artistic practice. Yet for Nemkova, identity is more about family than nationality. Growing up in a family of scientists has played a crucial role in shaping her worldview as an artist, though her relationship with science as an artist is nuanced rather than straightforward.

Despite coming from a family of scientists, she does not see herself as a science communicator through her art. Today, science has become a kind of new religion influencing every aspect of contemporary life. “When it comes to progress, true innovation happens in science — particularly in technology and medicine — as seen in the constant release of new products and treatments designed to improve, simplify, and extend human life. Science offers hope, motivation, and even consolation. In this sense, calling it a religion is not entirely wrong”. However, as an artist, clarifies Nemkova, science is not merely a subject to be explored with aesthetic curiosity but a deeper means of understanding human existence. “An artist working with science is not someone posing in a lab coat, holding test tubes. Rather, they are someone who studies, refining their perception of what it truly means to be human—something we know much about, yet still understand so little”.

For Nemkova, being a professional artist is, above all, about learning to train one’s inspiration rather than relying on spontaneous bursts of creativity. Everyday experiences, even the most mundane, can spark inspiration, but it is only in the studio, “an intimate, deeply personal space where time loses meaning” that intuition takes shape. At the same time, being an artist means living with heightened sensitivity, where every external stimulus has the potential to provoke an intense emotional response. “Being an artist,” she explains, “means living with the ‘condition of flayed skin,’ where anything that isn’t smooth can sting, triggering a deep, sometimes painful, reaction”. One of the most valuable lessons that years of practice teach an artist is patience, the ability to wait for a work to reveal itself fully. “Sometimes, you suddenly sense that something isn’t right, that the piece is asking to be left alone. You have to listen. It’s a meditative tension that can last for years. Then, one day, without warning, the dialogue resumes, and within a couple of hours, the work is complete”.

Nemkova’s artistic practice is rooted in an ongoing dialogue with matter—whether it is concrete and tangible, like sanguine pencil, watercolours, metals, and minerals, or more abstract, as in performances that in any case involve interaction with physical objects. “In the end,” she says, “a work of art is a three-dimensional form of dialogue with matter”. Material is not something to simply be shaped; it must be listened to. The creative process is a delicate balance of guidance and receptivity, leading to a pivotal moment when the material resists—a sign that the work has developed its own identity, its own will. This epiphany marks the moment she knows she has succeeded, even if completion is still some time away. Such an approach underscores a fundamental belief: only the artist can truly hear what the work has to say. More than that, the work itself is alive, having absorbed, through touch, the oxytocin released by the artist during its creation. “An artwork is an active entity that continues to live beyond the studio,” she explains. This philosophy is why Nemkova never delegates the execution of her pieces to artisans working from her sketches or models. Even when an assistant is involved, each work remains shaped entirely by her own hands.

A signature element of her practice is the visible presence of the creation process itself—technical edges, specks of colour, smudges, and even fingerprints are not flaws to be hidden but integral parts of the work. She also extends this idea to her installations, believing that marks left on walls or surfaces during the placement of a piece should stay there, as they are part of its evolving presence. When collectors acquire her work, Nemkova either provides them with detailed instructions for installation or oversees the process herself. Fortunately, she notes, “In recent years, the way people collect art has changed. Today’s collectors understand that the act of installing a work is part of the experience of owning it”.

At the same time, Nemkova resists the constraints of the neutral, sterile environment of the white cube. Her current exhibition, ´Broken Instincts´ unfolds in a single attic room, accessible only via a steep staircase and lit up so as to leave many areas in the shadows. A less curious viewer might struggle to locate all eight sculptures on display. But this mode of presentation is intentional—Nemkova believes that art should not always reveal itself immediately and entirely. Instead, it should be experienced and discovered gradually, evoking an emotional ebb and flow between fear and joy. This dynamic mirrors the process of falling in love—a journey marked by uncertainty, anticipation, and revelation, a constant oscillation between happiness and apprehension. In a way, all of Elena Nemkova’s works seem to be infused with the same chemical and biological phenomenon that we call ´falling in love´.

A perfect example of this is her work ´While I Was Not in Love, I Knew Very Well What Love Is´. In this piece, Nemkova uses gallium, a metal with a melting point of about 29–30°C, to create sculptures shaped by individuals experiencing emotional turmoil, some even undergoing psychological or psychiatric treatment. The warmth of their hands transforms the metal, making it a physical metaphor for the fragility and volatility of love itself.

Ultimately, art—like love—is never a matter of willpower alone. It arises from a complex, partly chemical interplay between matter, emotions, and time.