Tamara Zinovieva’s Adventures in Automatic Drawing

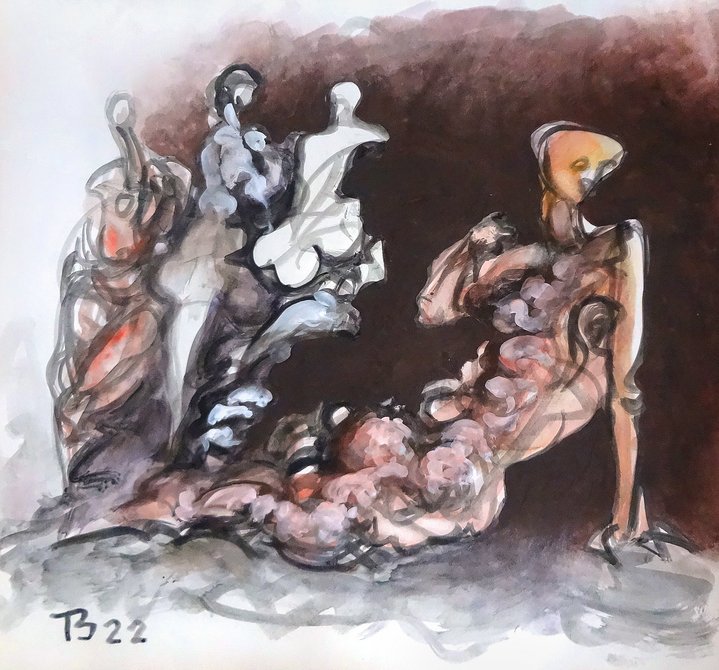

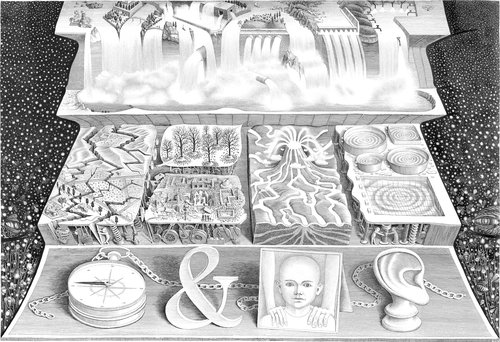

Tamara Zinovieva. Untitled, 1996. Courtesy of the artist

This Moscow artist has developed an original style and method of drawing in which, she claims, the brain is not involved at all.

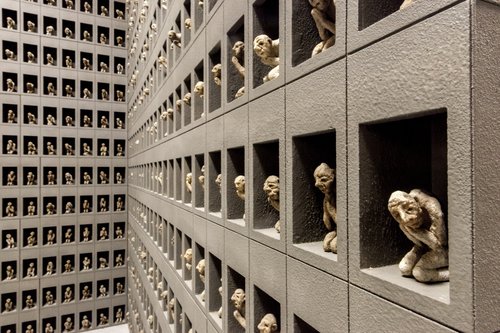

Tamara Zinovieva’s apartment in a residential block on the outskirts of Moscow is cramped with her artworks and contains enough material for a couple of museum retrospectives or at least a dozen gallery shows. Zinovieva (b. 1954) works using different techniques, some of them invented by herself. She adds a layer of watercolour on top of gel-pen drawings, and then another layer of graphics, and so on. She carves elaborate sculptures out of blocks of foam plastic - discarded packaging of electronic home appliances. She captures the sound of music performed live at jazz concerts in her drawings so accurately that musicians recognise the compositions immediately and often want to take them home. “Most artists like to draw musicians performing, and I prefer to draw their music. The biggest challenge for me is to transfer a linear structure of a melody into a spatial one of a drawing,” she says. She posts new works on social media regularly. All this looks like a harmonious and fulfilling artistic career. Yet Zinovieva’s path in art is anything but a typical success story. For decades, she dwelled on the margins of both official and underground Soviet art scenes, and after the collapse of the Communist regime, she has been largely ignored by both big state-run institutions and the nascent art market of post-Soviet Russia.

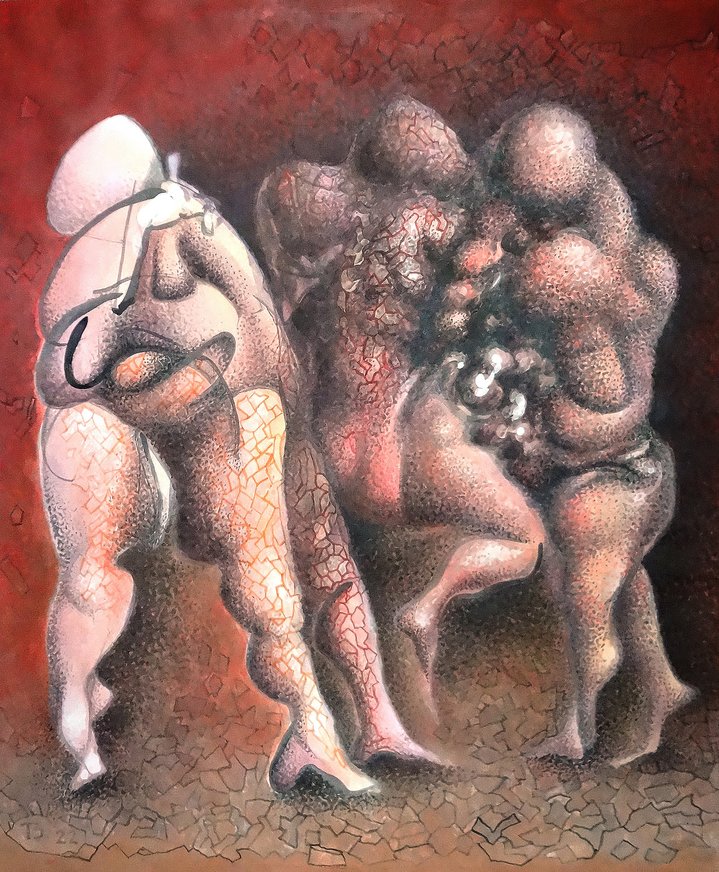

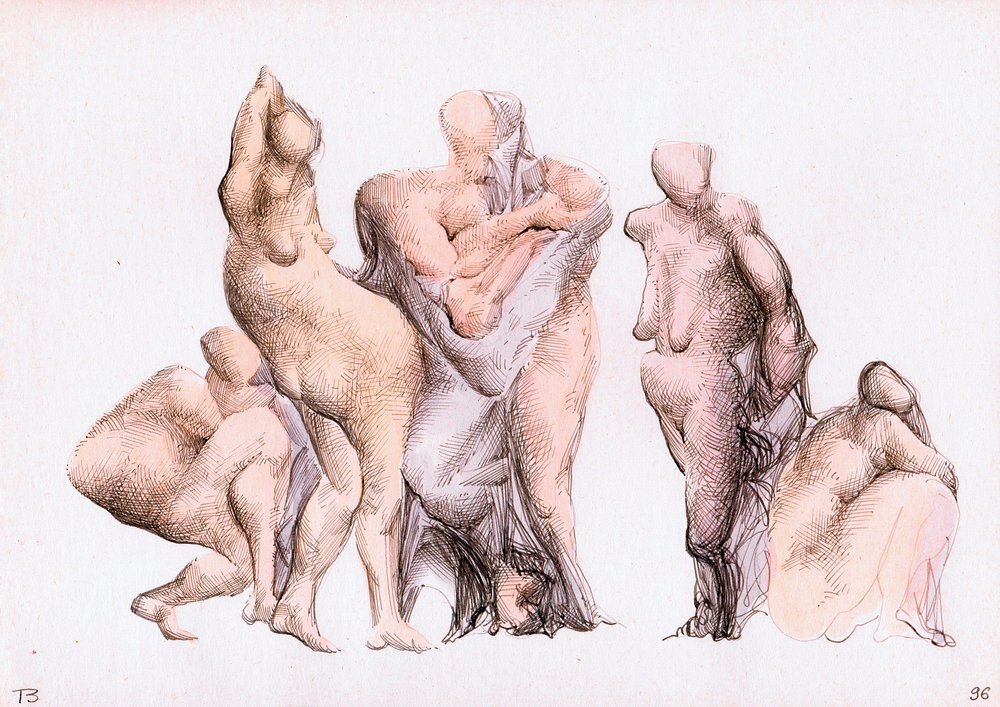

Zinovieva was born into a typical family of the Moscow intelligentsia, her father was a philosopher while her mother worked for the state press. “The first art I saw in my life was by Ernst Neizvestny – those big, heavy bodies,” – she recalls. Her father Alexander Zinoviev and the renowned sculptor of the nonconformist generation were good friends. “We would come to his studio where Dad and Neizvestny would drink booze and philosophise, while I was looking at the sculptures”. She began to make sculptures herself at the age of seven or eight, cutting them from pieces of driftwood she found on the beach during a seaside summer vacation with her parents. She never received any formal art training, dropping out of drawing classes where her parents enrolled her as a teenager. “I did not see the point of going there. I could learn it all myself from textbooks”. She still keeps many paintings from her teens and early twenties, astonishingly virtuoso yet wavering in style, from Fauvism to Realism to something close to German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) of the 1920s. Among them are portraits of her grandfather, a retired KGB officer, and her grandmother, made in the unusual technique of painted inverse bas-relief “in the ancient Egyptian fashion”, but carved out of foam plastic. Yet the idea of making art her profession did not occur to Zinovieva at the time. Her major at Moscow State University was Art History. “This was a tragedy of my life, I would have chosen archaeology but my mother objected”, she says. Later on, she started to join archaeological expeditions in Ukraine and in the South of Russia every summer as a staff artist. There she was doing meticulously accurate technical drawings of archaeological finds. That was how she made her living for many years, along with occasional contributions to the Decorative Art magazine. “Because of my father, nobody would hire me for any job, and when they did, they fired me very soon after,” she explained. Alexander Zinoviev, who had a different family by then, turned from a well-reputed Soviet professor with somewhat unorthodox views on Marxism into a dissident. He was exiled from USSR in 1978 for his novel ‘Yawning Heights’. Published in Switzerland two years earlier, it was a biting satire of the Soviet lifestyle.

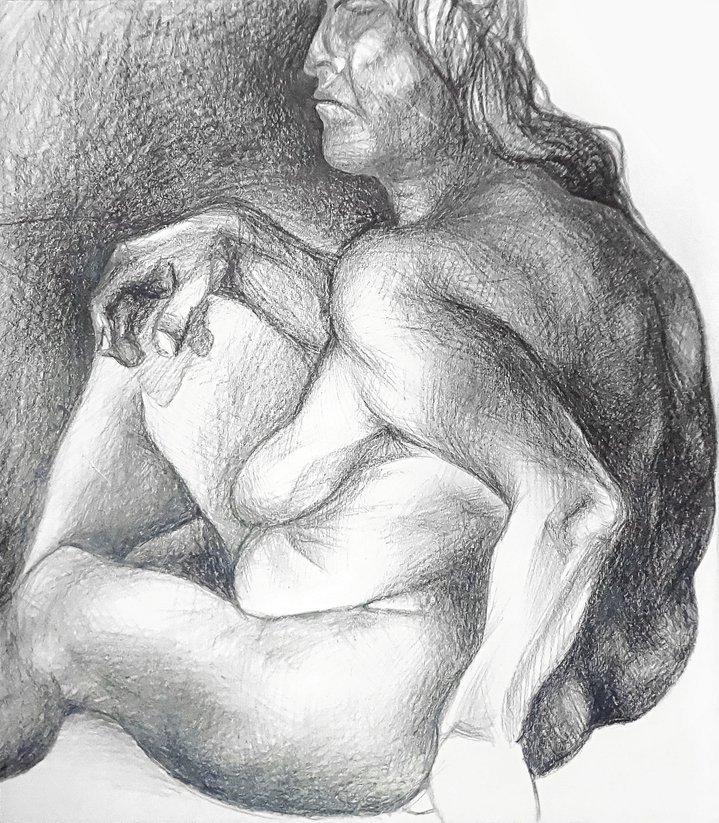

Zinovieva’s work in archaeological expeditions was a rigorous training for her hand and eye and it generated the habit of realism that she strived to overcome in her art. “When I draw from nature, it always turns out very accurate, and that’s not what I want”, she says. After a brief period of experiments with Primitivism, in vogue at the time, Zinovieva finally developed her distinctive style. It evolved from doodles she used to make absent-mindedly during lectures or tedious meetings at her job at the Ministry of Folk and Decorative art. “When I’m drawing, my brain is not involved – I can do two jobs at once, make art and think about something else, for instance, my college course programme”. (She managed to get a job teaching computer literacy to students in the late 1990s). In essence, it is automatic drawing in its purest form. “I never realised that until I read a book on Surrealism. Then I thought: oh, that’s what it’s called!”

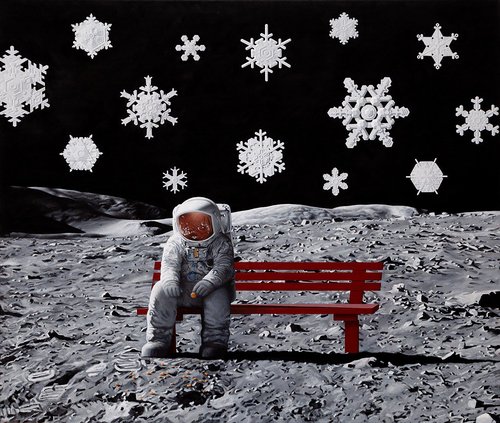

However, she thinks her style is closer to New Figuration than Surrealism. “In Surrealism, the subject-matter is important, one has to invent a visual metaphor.” This approach is completely alien to Zinovieva. “If I needed to invent a metaphor I would express it with words.” Gradually, the random lines and curves drawn by her pen evolve into figures that look semi-abstract yet vaguely anthropomorphic, full of volume and life. Sometimes, she adds colours to them and most often these are the hues of the human skin. A tiny person with a boyish figure Zinovieva creates paintings and graphic works that celebrate the flamboyant, curvaceous human body in all its gravity, imperfection, and vitality. Zinovieva counts herself among “artists with a sculptor’s mind”. Emotionally, she perceives the image she creates not as a combination of colours and lines, but as an object standing out against its background. Sometimes, allusions to the compositions of classical paintings can be traced in her works, revealing her background as an art historian. These references are not deliberate, they surface from the subconscious. “It may start relatively figurative and then become quite abstract, or the other way around”.

One would think that with her style and her family background, Zinovieva would blend seamlessly into the nonconformist art scene of her time. But, although she visited underground art exhibitions that took place in private apartments, she never became a part of the circle. Zinovieva lived a solitary life, and not by choice. Life was harsh in the Communist paradise where even the basic groceries and consumer goods were hard to come by. “I never had time to hang out with other artists back then. My mother worked long hours in editorial offices so I had to hunt for food in stores all over Moscow and sew clothes for both of us. Everyday life was exhausting,” she recalls. It was not until late 2010s that she found an artist community she could join. Called Lega, it is a space in the centre of Moscow, where a collective of like-minded artists periodically puts up group and solo exhibitions. When I attended the opening of a show where Zinovieva took part, one of the guests tried to pocket one of the exhibits, a notebook full of her drawings. “He would have walked away with it if I had not stopped him”, the artist told me triumphantly. It seemed to me that she was genuinely flattered.