Street Artist Slava PTRK on Nightmares in Broad Daylight

Slava PTRK in collaboration with Vladimir Abikh. Street Dirt. 30 portraits on board: dirt on latex paint, cellotape, 120x180 cm. 46 photo portraits: digital print, 35x40 cm. Yekaterinburg, 2013–2015. Courtesy of slavaptrk.art

This Russian artist who fled to Montenegro last year, has unveiled a new exhibition in Budva, a piercing commentary on the current tragedy unfolding before our eyes.

A derelict ruin of a church, walls precariously cracked and broken, paint peeling in layers and overgrown with moss and weeds from the inside stands with its gasping windows like empty eye sockets, in the middle of nowhere. Upon closer look there are rhythmical black markings around the inner perimeter, it is dripping paint as if fired from a machine gun, but get even closer and you will see within these splashes the silhouettes of multiple non-existent candles – a kind of anti-shadow, defined only by the surrounding blackness.

This powerful image of dark and light, is part of Russian street artist Slava PTRK’s (b. 1990) (declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities) latest ‘black series’, created since moving to Montenegro in the autumn of 2022. Now numbering over a dozen such interventions in found environments with black paint, “it is about my inner feelings and emotions in reaction to what is happening, but rather abstract,” explains the artist.

He creates an immersive conceptual space in a fine balance between existing environment and street art alteration. And yet, most viewers, and his thousands of subscribers will never see the piece in reality — it might likely be soon destroyed – but will live on forever in virtual archives. This bridge between the extremes of physical and virtual space is common for most contemporary street artists.

Slava PTRK began his experiments as a teenager on the streets of his provincial hometown in the Urals. But having moved to Ekaterinburg and enrolled to study journalism, the potential of street art to convey messages began to crystallise. His first work in the genre of social commentary was Kirill piggy-bank, a stencil of the Russian orthodox church patriarch portrayed with a hand dropping a coin into his head. “That’s where it all began and could have ended if it had been in 2018. But in 2010 there were no laws on insulting the feelings of believers, and other damned initiatives from our state”. So, everything went smoothly. PTRK was part of a street art boom in Russia throughout the 2000s and the next decade developing from graffiti to more conceptual projects, including such artists as Tima Radya (b.1988), Kirill Lebedev (Kto) (b.1984), Misha Most (b.1981), Vladimir Abikh (b.1987).

Yet PTRK’s personal journey and journalistic background, took him on a trajectory of social and political commentary. For example, in Vladivostok a series called ‘Obstacle Course’ shows images of wheelchairs and buggies on the city’s many dilapidated staircases with no ramps, pointing to the negligence of city authorities. In 2015 in Ekaterinburg, he used old crutches and walking sticks he bought online to write on the façade of the city’s hospital ‘Land of opportunities’. The ironic critique was removed the following day and he gave away the crutches to those who needed them.

In the project ‘Street Dirt’ (2013–2015), together with Vladimir Abikh, portraits of the homeless were outlined with water repellent paint and placed along the streets of Moscow to be splattered with mud and hence reveal the image of these city tramps, invisible, ignored and likened to dirt.

An iconic project in 2018 which gained much attention took PTRK away from graffiti into performance. ‘Fuck It Let’s Dance’ arose as a somewhat lyrical work, involving a hundred performing dancers filmed waltzing in the Ekaterinburg snow and eventually stopping in a textual formation to spell out the work’s title. Yet its message, “that you need to remain optimistic in any situation, no matter what happens around,” seems a lifetime away from today’s realities.

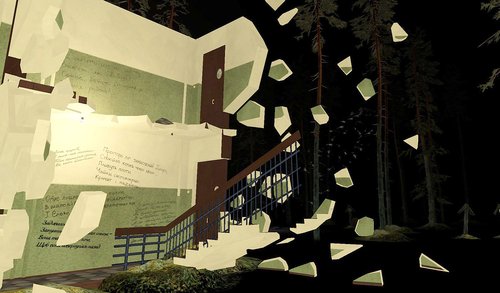

By contrast, the project ‘1999’, done in collaboration with the indie music group SPBCh in 2019 is pertinent to the current context. It is a two-part project, the first of which takes the form of research in which the artist collected interviews with Chechen war participants taken by their relatives. This material was then used to create a multi-layered installation incorporating quotations from these witness accounts into the setting of a derelict army base, intertwining the fabric of these two narratives, deliberately stylising the Chechen quotations to the patriotic war rhetoric in the original building. Thus, for example, a soviet banner with a quote from Suvorov “All the firmness of military government is based on obedience, which must be kept holy.” Hangs above an inscription in a similar font added by the artist from their research materials “when an order is given, the soldier does not know whether it is a crime or not.”. To say that this project is relevant today is to say nothing. It rings with a piercing resound. Unbelievably for today’s context, an exhibition of this project was mounted by a gallery in the fashionable Winzavod art factory in 2020.

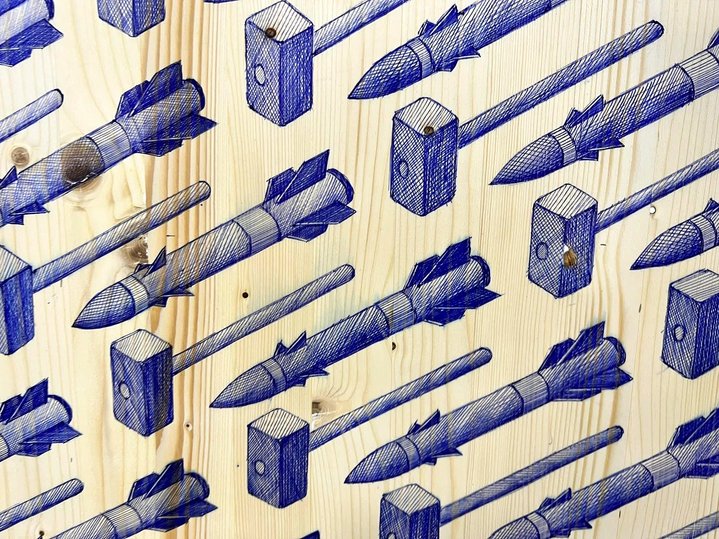

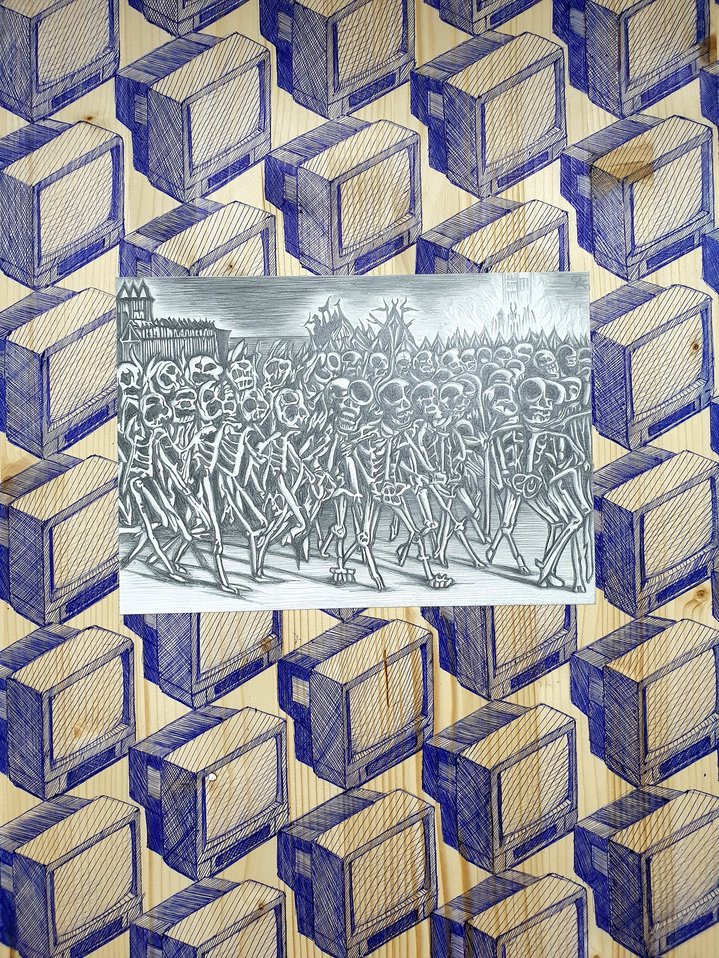

Like many of his contemporaries, in 2022 Slava PTRK left Russia. His latest show ‘Dreams of Reason’ opened in the new Montenegro European Art Community gallery and will run until 15th of May. Going by the motto ‘don’t get used to it’ the artist presents an array of imagery triggered by perception of events from the frontline. Obsessively scratched into wooden panels with biro are repetitive patterns of soldiers, weapons, and trenches. Pinned to the blocks are A4 pencil drawings of AI generated images alluding to the propaganda on TV screens. Zink box cut-outs are strewn across the floor evocative of coffins and the throwaway attitude to people’s lives. Wax seals (a pun on clichés, the Russian word shtamp is the same) of Russian/Soviet popular mentality plugging black bullet holes around the gallery walls are not immediately obvious. A further room shows a large screen of an edited video of the Sims life-simulation videogame where the characters are put in an air raid situation, hiding on the floor. While driftwood in front of the screen is arranged like corpses.

The show is a patchwork of obsessive recurring thoughts which haunt the artist like so many of us trying to piece together from the barrage of fragmented information our shattered world and worldview, an impossible task. The exhibition is not one cohesive artistic expression, and it is not intended to be because we are all still in the thick of it. As an accompanying text written by Daria Epine concludes: “What brings us here, and how do we keep our eyes open while the black, sticky goo continues to drag us down into the abyss?”

Slava PTRK. Dreams of Reason

Montenegro European Art Community

Budva, Montenegro

18 April – 15 May, 2023