Sergei Limonov: сollecting art in St.Petersburg

In St. Petersburg, a city where the natives, and particularly the local arts elite, are always keen to tell you that they live in a “city-museum”, Sergei Limonov is a representative of a new generation of art collectors.

In the West, if we’re asked to conjure up an image of a Russian art collector, one of two characters quickly spring to mind – either it’s a Bond villain, stroking his cat, surrounded by masterpieces, as he hatches a devious plot to take over the world, or a crass, nouveau riche oligarch snapping up football teams and superyachts, along with assorted artistic trinkets at the world’s leading auction houses.

Quietly spoken and dressed with understatement, Sergei Limonov, a man who is gradually establishing himself as one of Petersburg’s most dedicated and thoughtful collectors, paints a more nuanced picture.

Under the Soviets, officialdom, the party line and rigid institutionalization of the visual arts left little space for private collectors and patrons of the arts. That meant, according to Limonov, that collectors in the post-Perestroika era have largely been starting from scratch

“There was no real tradition of collecting in the Soviet Union, so Russian collectors are like children. What’s more, they’re children born into an orphanage, without parents to guide them,” Limonov says, speaking in a rooftop restaurant in the heart of Petersburg.

Limonov does admit that for the new generation of Russian collectors, the learning curve has been steep, with bumps along the way. “The collectors are feeling their way into developing a strategy for collecting. They started merely with their tastes – what they like, what they don’t like. Then they became more systematic, they started to do a lot of reading, they became more erudite and informed. Nevertheless, I can see in my own case and among my colleagues that we often started out with some fairly odd purchases.”

Economic factors have also played a major part in the development of this new generation of Russian collectors. In the mayhem of the 1990s, the era of “primary accrual of capital”, as Limonov puts it, using a popular Marxist euphemism for the brutal, smash-and-grab tactics of Russia’s first wave of capitalists, collecting was the preserve of the lucky few.

In the decades that have intervened, a middle class of sorts has been established, allowing more modest collectors to enter the market.

“As this class has become more prosperous, it realized that it doesn’t need a fourth black SUV or to travel to expensive resorts – all that becomes very repetitive. Why open a third restaurant? Or service a 300th client? The novelty dies out and you start looking for something more. I think that Russia is on the verge of a real development in its art market and collecting.”

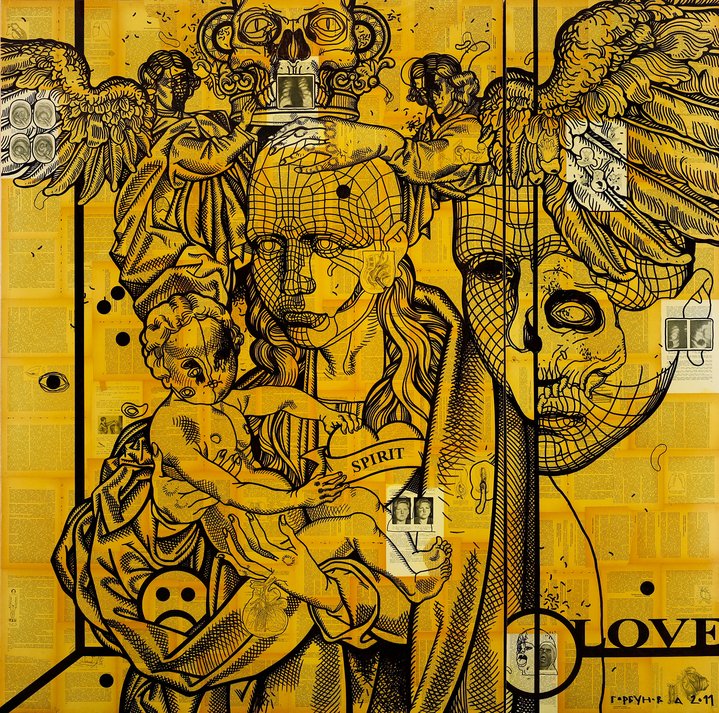

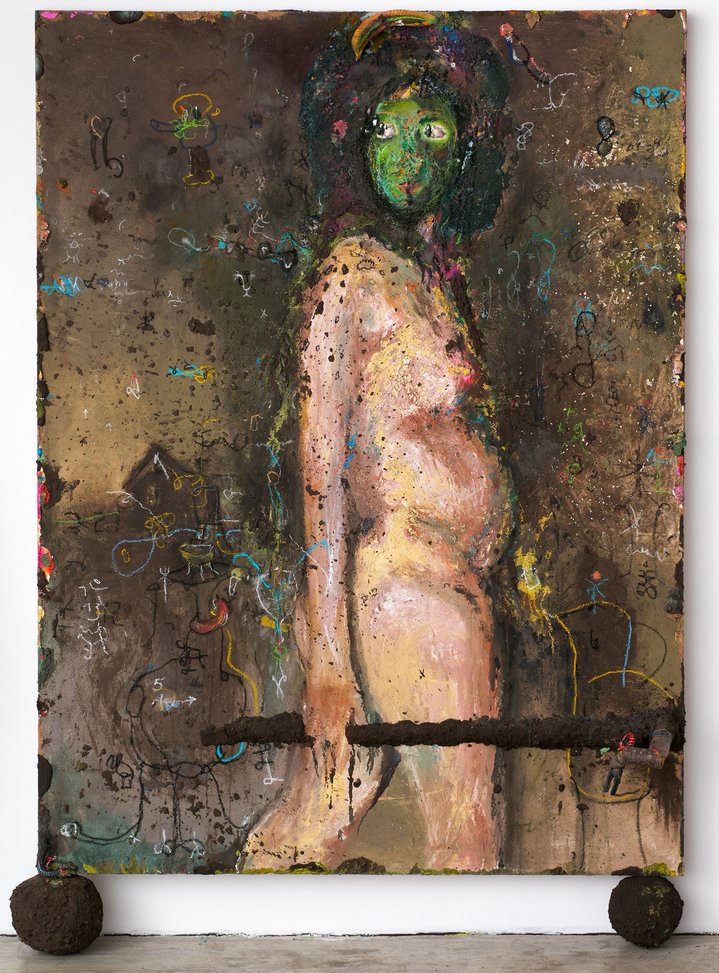

Limonov’s preferences and principles are clear in his collection, perhaps best exemplified by the first work he shows me – Leonid Tskhe’s (b. 1983) ‘Place for the Scarecrow’, a disturbing, distorted figurative image bordering on primitivism – and by the other artists he lists, such as Nestor Engelke (b. 1983) and Alexander Tsikarishvili (b. 1983). “I try to collect tough art that may repulse you initially, but you have to overcome that for the art to push you to a new level. That’s the real catharsis and joy that comes from a work of art.”

This drive to challenge himself through his selections can be seen in his guiding principles – Limonov avoids buying works by established, deceased artists (“too easy”); he is keen on abstract works that won’t limit his response to themes and figures that are depicted too literally; and he believes that the mark of a true collector is someone who buys large installations that can’t be hung on a wall to match your living room carpets and curtains.

The latter principle is perhaps best exemplified by his appreciation of the works of Petersburg’s ‘Sever-7’ (‘North-7’) group of artists – unwieldy, immersive installations that verge on the shambolic with a wealth of disparate, smaller works within them that call out to be studied in greater detail.

For Limonov, they are demanding works that force spectators to develop, drawing on their own creative potential – something that is entirely in keeping with his own approach to collecting. “You need to find an outlet for your creative impulses, so what do you do?” he asks. “You don’t paint that well, the poems you come up with aren’t that good, you can’t shoot a film. Collecting itself, however, is a way of realizing that potential – the process of making a choice becomes creative.”