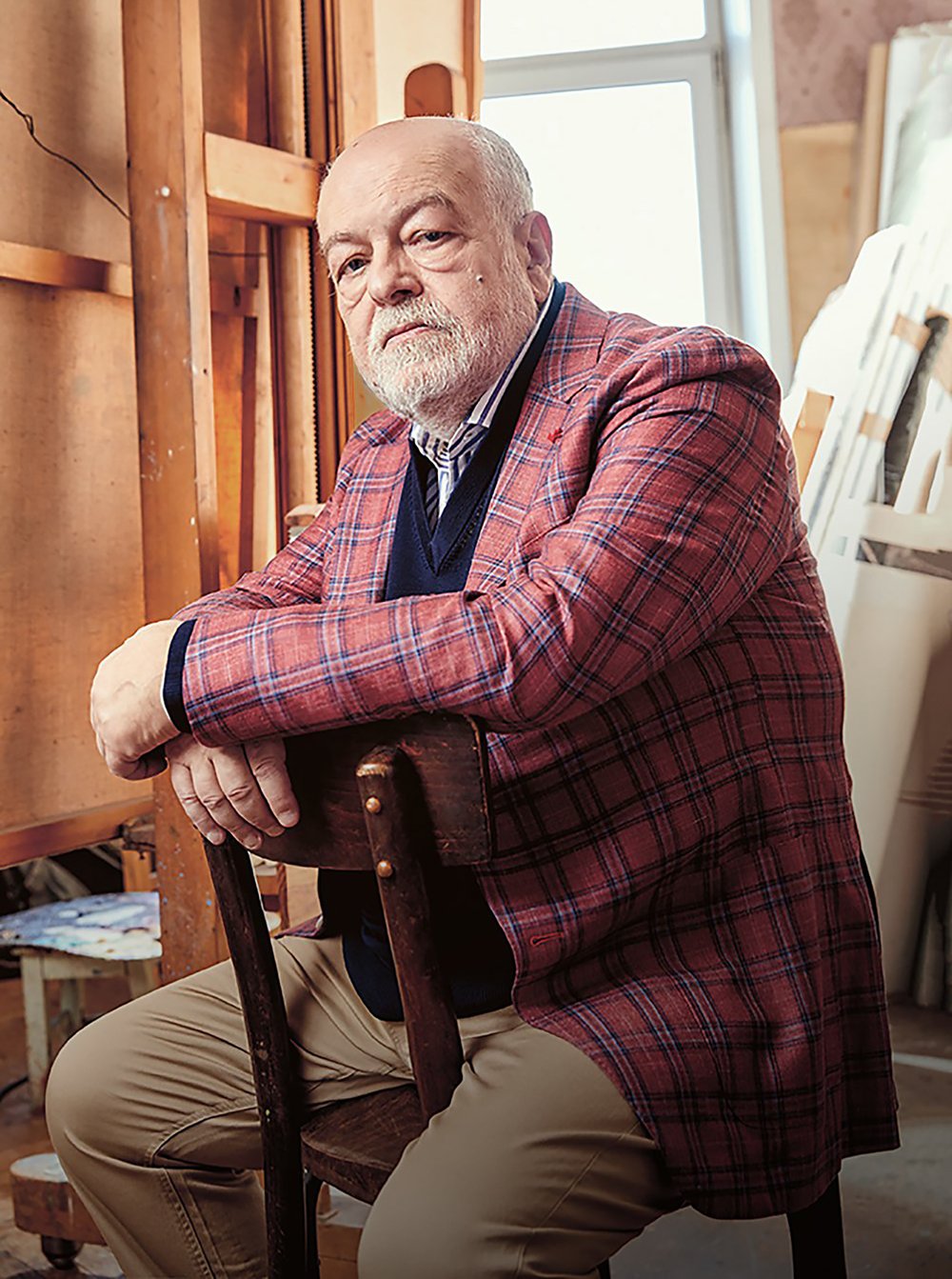

Semyon Faibisovich is a misfit and he's proud of it

Photo by Pavel Krukov. GUM-Red-Line project. 2019

Faibisovich’s entire biography is a series of negations and contradictions. He belonged neither to the Moscow Conceptualists nor the Sots-Artists, and he disagrees sharply with their relationships to their Soviet subject matter.

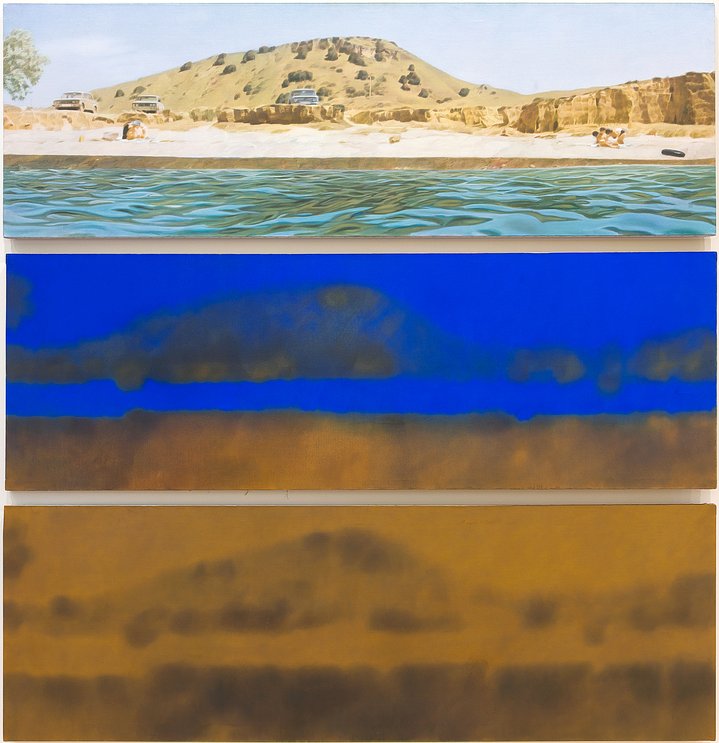

Instead, he “followed his own path,” remaining an outsider among his Moscow compatriots until his work was discovered by Western collectors at the Gorkom of Graphic Artists, the city’s first sanctioned space for “unofficial” art. He was not trained either as a graphic artist or a painter; he preferred to remain an autodidact, with an air of cheeky juvenile abandon, working first from books and newspapers, then using his own photographs. He recorded everything that caught his keen and observant eye.

He found solace not among the artists of the September 1974 “Bulldozer” exhibition, but at Moscow’s Pushkin Museum’s famous 1975 exhibition of contemporary American art, where he first saw works by famous photo-realists like Chuck Close and Richard Estes. Having begun similar experiments of his own many years earlier, he was pleasantly shocked: they were “demonstrating a language, and I wanted to learn (so as) to have a conversation in it.”

Having spent the majority of the last three years in his new home of Tel Aviv, Faibisovich is now returning with a bang: in late March, the New Tretyakov Gallery, one of Moscow’s foremost museums, will host a massive retrospective of the artist’s work, his first major exhibition since his “My Moscow” show in 2017.

Visitors will be treated to a longitudinal look at Moscow over the years, stretching from his observations before the rise of perestroika to his most recent documentations of a Moscow that is slipping away through our fingers. The irony should not be lost that it comes on the heels of a colossal show by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, some of Faibisovich’s greatest competitors — if not in style, then in market share.

Nearly two months before the exhibit opens, I sat with Faibisovich in his Moscow apartment. The space itself seems to have escaped the progress of time. It feels ageless but certainly not new, like a time capsule of the Moscow in his paintings. Faibisovich himself is quiet, even shy, as we sit down in his kitchen, which was always the heart of any Soviet home. Unassuming though he may seem, his sharp curiosity quickly shows through.

Before I could even get my first question out, he wants to know all about our publication: who our audience is, how long we have been around, and how well-acquainted I was with Russian art. He picks up on my accent immediately, and later on, he’s quick to share stories about his brief time in New York in the early 90s.

One would be forgiven for considering Faibisovich a documentarian. He is loath to indulge in nostalgia, but he is quick to decry the “cleansing of [his] Moscow,” seeing the endless march of “flagstones, asphalt, and fences” as an assault on the city that has served as his muse through decades of regime change and his own movement around the world.

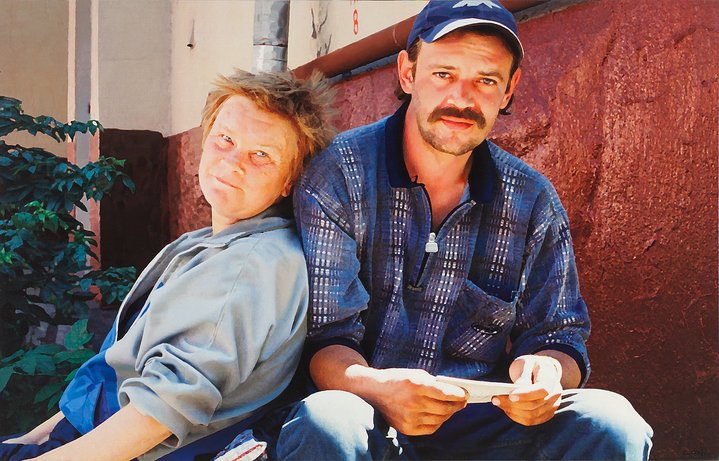

“Everyone else, including (Moscow’s ex-Mayor Yuri) Luzhkov, was only concerned with façades," he said. Even Stalin gets an unexpected bow. “Behind all the horrors that he built, there was still life in the courtyards. There were cracks in the asphalt, bird droppings, poplar fluff. It was always the garbage and the vacant lots that attracted me. And now...there's nothing to work with anymore. No bums, no homeless dogs. Everything has disappeared, the stands, the kiosks, any semblance of private life." Indeed, these marginal characters are consistently the ones which fascinate Faibisovich the most, even as those margins continue to recede further and further from the public eye.

He is careful to stress the equanimity of his relationship with the city. Regret as he may the changes that he sees, he draws a line between himself and those artists who would take a more active hand with urban “interventions.” He wants to remain a passive observer, even as he watches the changes wrought by Moscow’s current administration as it whittles away at the cracks and corners that he so treasures. Sad as it is to watch, he does not believe that it is the duty of artists to guard either their work or their inspirations. “The artist is doomed to solitude,” he says.

When he was first approached by Western collectors in the midst of perestroika, he went through a “nerve-wracking process” as he learned to part with his works. However, he came to see that giving away as the essence of the artist’s work.

The only thing sharper than Faibisovich’s eye is his tongue. The artist stopped painting for 12 years, from 1995 to 2007. What caused the break was what the artist perceived as a narrowing of the market, inspired by an effort to present to foreign critics a “unified front” and a non-existent single artistic movement in Russian art. Faibisovich saw a need for independent and unbiased opinion writing and took up the pen rather than his brushes at the high point of Russia’s former independent media in the 1990s before the wind changed.

Faibisovich is loath to be pinned down in any one place or time. He recounts how he left New York in a hurry back in 1990 after his gallerist at the time, Phyllis Kind, tried to explain to him the realities of staying consistent in the New York art market. He speaks about the irony of how, “in the Empire of Evil, I had done exactly what I wanted...then ended up in their Little Apple, and there, in the Empire of Freedom, they were trying to tie my hands.”

The natural response to a meeting with Faibisovich is to search out the Moscow whose disappearance he bemoans. Indeed, walking out of his apartment, I was surprised to see stray cats warming up underneath the engine blocks of the cars in his courtyard, and was lucky enough to take an aging trolleybus back to the metro station.

Describing some of his early subjects, he recounted the scene he would see daily while using public transport on his way to the center of Moscow from Yasenevo, a distant southern suburb of Moscow. “The face of those people was the face of power itself. But there were two worlds: the world of the buses from Yasenevo in the morning and the internal world. One was created by the Bolsheviks, and the other — by God. They exist in parallel, and every once in a while, the world of God peeks through to give the former some sort of justification.”

Although hard to see from within the modernized confines of the Moscow of the powers that be, Faibisovich continues to search for that hidden touch of the divine — even if he has to do so alone.

Obviousness. Retrospective of Semyon Faibisovich

Moscow, Russia

27 March – 28 July