Rustam Aliev: showing Russian art on the European border

Dairy tycoon Rustam Aliev is building a private museum of Russian art at the country’s westernmost outpost, Kaliningrad – the birthplace of Immanuel Kant.

Rustam Aliev has taken a long path through the history of Russian art in building his collection. It moves from the 19th century, to Socialist Realism, to Soviet Nonconformism, arriving just now at contemporary art, which will be a cornerstone of his Russian Centre of Art, a short walk from the tomb of philosopher Immanuel Kant in Kaliningrad.

As he builds his private museum in Russia’s westernmost city that used to be the German city Königsberg, scheduled to open at least in part by the end of 2024, his goal is to bring young people geographically cut off from the rest of the country to Russian art.

Kaliningrad is 1,250 km to Moscow, approximately the same distance to St. Petersburg, and due to covid restrictions, international borders have to be crossed to get to “the mainland”, as Kaliningraders call it, “we can’t drive there, but only fly or take the train, or a sporadic ferry to St. Petersburg,” he says. “Our Kaliningrad youth is Europeanized. There is a reason for this. Before Covid, families would drive to Europe every weekend. It’s 300 km to Warsaw and Vilnius and 600 to Berlin. Everyone traveled around Europe a lot. It is much cheaper, faster and more convenient than traveling to Mother Russia.” As a result, “our children do not know Russian art,” he says, compounded by the fact that “we have no strong museums” in Kaliningrad.

His parents were among Soviet settlers in the Kaliningrad region after it was taken from Germany in 1945. When he was a child in the 1960s, “there were still destroyed buildings,” recalls Aliev. In the post-war years, authorities had focused on putting up housing, rather than museums.

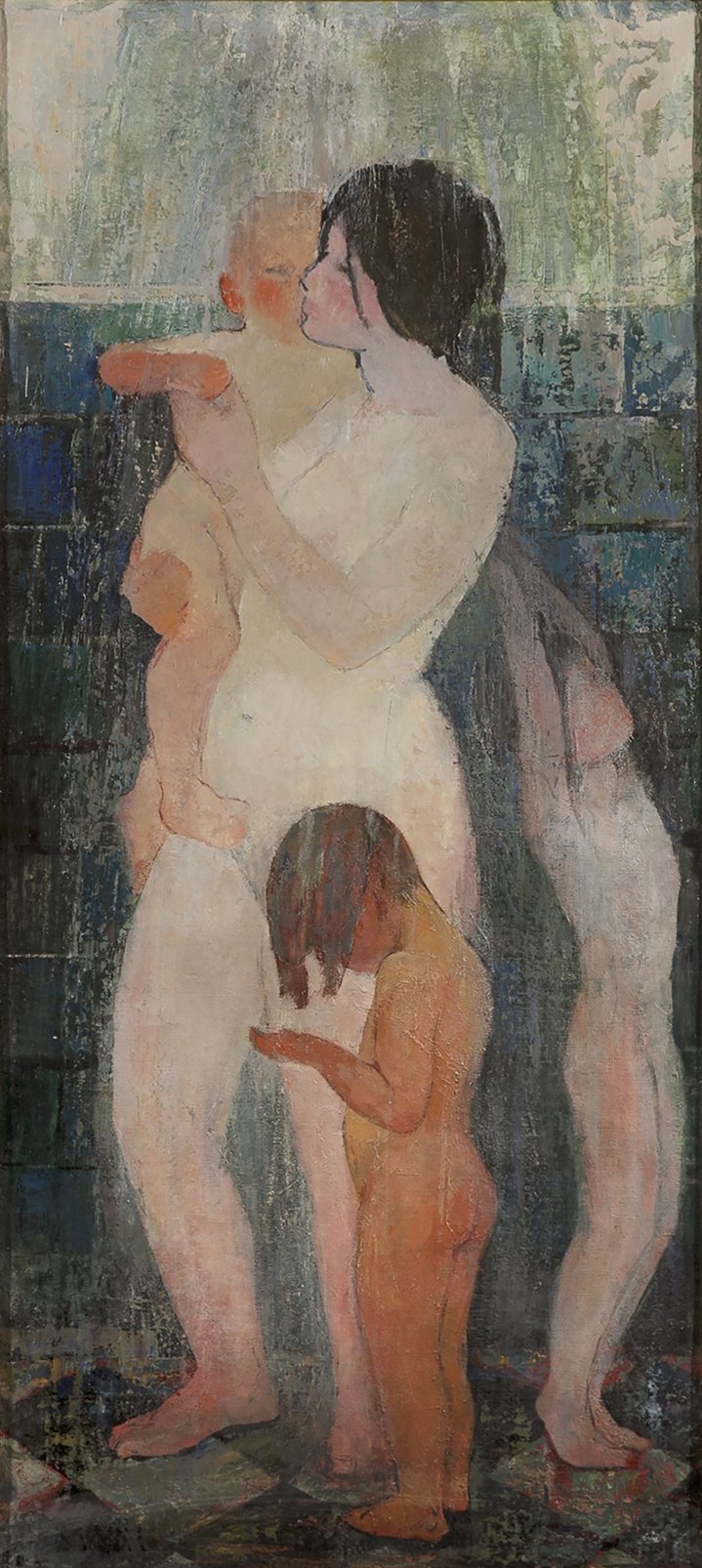

With rare exceptions, Aliev has practically stopped buying works of the 19th century Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers) movement of realist artists. He is seeking out Socialist Realist works, which are hard to find, because they are mostly in private collections and museums.

Aliev recently made major purchases of paintings by Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021) at auction and from the late artist’s family and other nonconformists at Sotheby’s and Christie’s and “one of the best works of [Vladimir] Dubossarsky (b. 1964) & [Alexander] Vinogradov (b. 1963)”, the former artistic duo, ‘Big Paradise’ (for 239,400 GBP at Sotheby’s, June 2021).

“I love the work of [Oleg] Vassiliev (1931–2013) and [Erik] Bulatov (b. 1933),” he says of nonconformists in his collection, which he has documented in a new catalogue. He bought Bulatov’s ‘Urban Painting’ at Sotheby’s in December 2021 for 189,000 GBP and Vassiliev’s ‘Figure in a Circle’ at the same sale for 220,500 GBP. “I buy, first of all, what I like. Even if I don’t understand art at some stage, I try to figure it out, because if I had been asked three years ago if I would buy nonconformists or contemporary art, I would have said, ‘keep it away from me!’ Now I understand that it is needed. I am starting to look at acquisitions not as a private individual, but as the head of a private cultural enterprise, the Russian Centre of Art, where I am starting to understand that, while subjectively I might not like it, the collection must be formed, because there are people who do like this.”

Kaliningrad’s governor Anton Alikhanov has allocated riverfront land for the Russian Centre of Art near the Königsberg Cathedral where Kant, who never traveled out of the city, is buried. Moscow’s State Tretyakov Gallery will soon have a space nearby, too, a part of a regional cultural centre showcasing federal arts institutions. The sites are both near the stadium built for the 2018 World Cup hosted by Russia.

Aliev, who grew wealthy as the owner of a dairy conglomerate, is self-funding the construction of his approximately 16,000 sq. m. centre (with about 5,200 sq. m. of exhibition space, plus a bookstore, cafe, lecture halls, a studio for classes and an underground garage). He restored a German villa in Kaliningrad as his home, now a tourist attraction. For the art centre, he was inspired by the concrete of the James Simon Gallery on Berlin’s Museum Island designed by David Chipperfield Architects. The pandemic interfered with plans for Polish and German specialists to work on the building to properly process the concrete and attain the correct light colour tone. Only the fifth Russian firm he turned to has more or less succeeded with the technique, he says.

“We have to go along this path, or wait three years for the borders to open and will they even open in the way we were used to before the pandemic? No one knows, but we must build,” he says. “We have made modest progress. The rate of construction is very slow, but I’m not upset because after all it’s not a commercial project first of all. Secondly, there are no loans. I am building 100% with my own money.”

The Kaliningrad region (population just over one million) has become a major tourist attraction for Russians during the pandemic, drawing a record of nearly two million visitors in 2021, the governor said in December. Aliev acknowledges that “people from Russia come to Kaliningrad not to see Russian art but to see Germany” in the form of a trophy acquired by the USSR. The Russian Centre of Art will devote about 700 sq. m. to Königsberg art, which he collects, including works of teachers and graduates of the Königsberg Art Academy and from the pre-war artists’ colony at Nida, a village on the Lithuanian side of the Curonian Spit (the other side is part of the Kaliningrad region). He also intends to work with Europe, although there might be obstacles.

“There must be art history collaboration,” he says. “Often, politics interferes in art and tempers all of this. I don’t know the position of the authorities, to what extent they will be favourable to this question. I can’t even say. Of course, if there is a possibility, we will do this and everyone will welcome our collection going to Poland, Germany, Lithuania or some collection coming from there for temporary exhibition. I can’t even answer this question, because it doesn’t depend on me to a large extent, but on the position of the authorities. It is a complicated situation. We all know this very well.”

Aliev sees the need for contemporary art through the prism of his older children. (He is involved in a highly-publicized custody battle over his small daughter).

“I realized that my children know nothing about Russian art, but know European art very well, because they have studied or are studying abroad,” he says. “They see a lot, are taken places, but they are taught and given European material.” He has taken them to Moscow and Petersburg’s central state museums to fill the gap.

In St.Petersburg, he also made a point of visiting Erarta, Russia’s largest private museum of contemporary art, and was stunned by the number of young people there looking intently at art that “they can’t see in their smartphone”, a phenomenon he wants to repeat at the Russian Centre of Art.

“I see why classical, academic art is not interesting to children. Before, there were no cameras, no smartphones, so artists captured a beautiful moment, a beautiful landscape, painted it and people hung it up in their homes,” says Aliev. “Now, this is all in the past. Now, everyone can download all these beautiful landscapes in the world. So they see all of this. It’s not interesting for them to see the same thing on the wall at home or in the museum. It’s interesting for them to see something unusual, some kind of created art object, made not by nature, but by man. And everyone does this differently.”