Rostislav Lebedev: dark mirrors and a laugh for our times

One of the prominent members of the Sots-Art movement has unveiled a new solo exhibition at Moscow’s pop/off/art gallery.

The first time I saw Rostislav Lebedev’s work, I was caught off-guard. In 2009, he made a series of painted black lacquer boxes titled ‘Treasured Fairy Tales’. Now saccharine souvenirs decorated with scenes from Russian folktales, the boxes have a deeper history as an affordable medium for distributing and popularizing academic painting in the late nineteenth century. In the Soviet period, the practice became a secular activity used to reemploy icon painters from Vladimir Region. The delicate borders and detailed, intertwined scenes on such boxes entice viewers to look closer, as I did. On one of Lebedev’s boxes, I noticed a field of phalluses. On another, squirming in the background, were copulating animals.

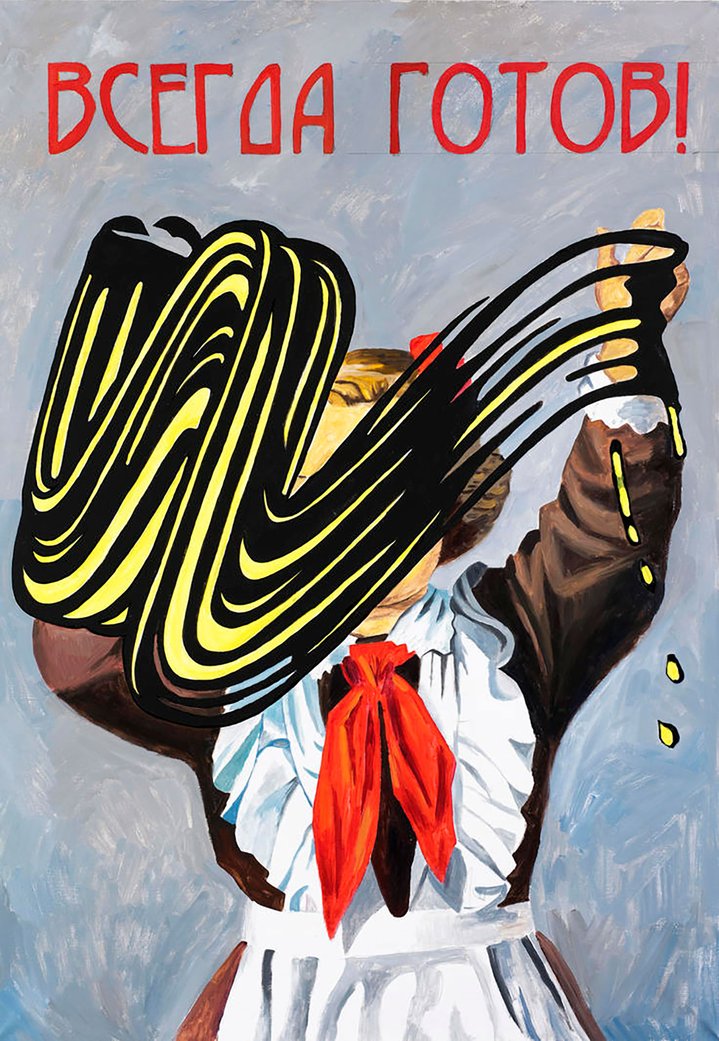

“The hardest part was finding someone to paint them,” the artist said with a chuckle in our recent conversation in his studio. Because many of the workshops’ commissions now again include icon painting and come from government institutions and the Orthodox church, several painters turned Lebedev down, citing concerns about losing larger contracts. Knowing this context sharpened what felt like an adolescent joke into a critique of the borders of the sayable. This margin — where serious critique and shallow quips overlap — is the space Lebedev loves to inhabit. The current exhibition at pop/off/art Gallery, titled ‘Between Propaganda and Frivolity’ features Lebedev’s latest efforts to slide along the ideological contours of our present moment with his traditional mix of images and wordplay. There is a painting of Donald Trump screaming. A funeral scene for the late Russian rock star Viktor Tsoi. Even the blanket that your grandmother’s had for decades.

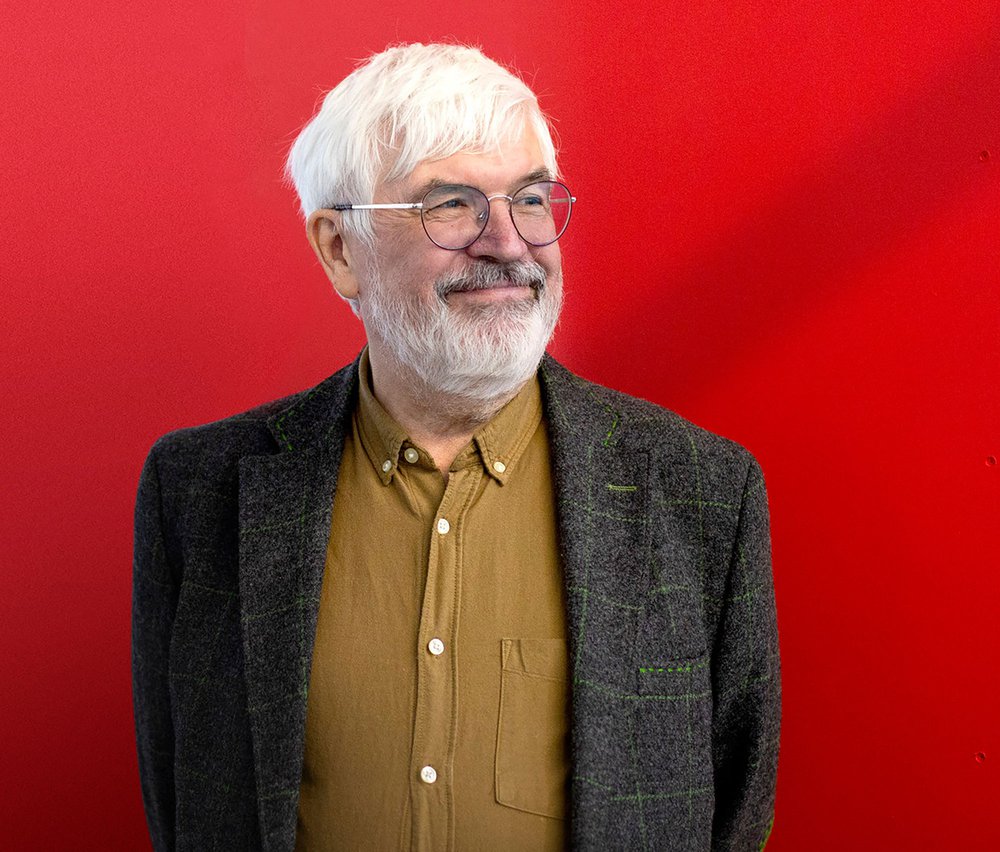

Lebedev (b. 1946), who just turned 75, comes from a generation of unofficial Moscow ‘Sots-Artists’. In the late 1960s, he joined what later became known as the ‘Ulitsa Rogova’ Group, where he met with artists Boris Orlov (b. 1941), Dmitry Prigov (1940-2007) and Igor Shelkovsky (b. 1937), among others. From the early 1970s, they began making slogans and stock images of the Communist Party and Socialist Realism the fodder of their work. “I actually didn’t like the name Sots-Art,” he told me. “This was [Vitaly] Komar and [Alexander] Melamid’s idea. I suggested something like ‘beyond Socialist Realism’.”

Lebedev played a key role in distributing Pop Art among his peers, translating Lawrence Alloway’s 1974 book American Pop Art. He eventually went to New York in 1989 and 1991. “This was the first time that I felt valued as an artist,” he said. “Though people there didn’t say anything in particular, it was about how they interacted with me. They respected what I was doing, rather than just saying, ‘Oh, an artist, he’s just over there drawing something.’” One of the key works in the current exhibition is a wooden triptych, at the centre of which is a grey board with the phrase “РАНЬШЕ БЫЛО ЛУЧШЕ” (“Everything was better back then”) painted across it in faded, stencil-like lettering. Was it? When I asked him about his relationship to the Soviet Union, his otherwise effulgent pace of storytelling slowed. “You know, I do not really have anything good to say. In the 1990s, things were very difficult. Now, it is in a way even harder, because we have begun to return to the Soviet Union. Back then, it was difficult for me to live. I wouldn’t want to return to that now.”

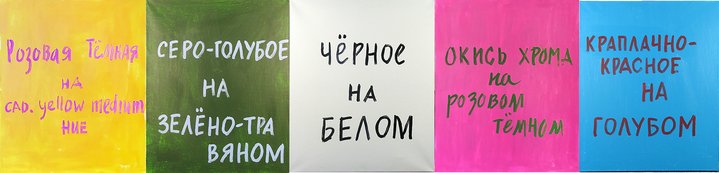

Lebedev’s works reflect the conflicted relationship that his generation maintains with their past in the Soviet system — one that is often inflected by the hazy, obscuring lens of nostalgia, tainted by a roller-coaster of economic and personal tragedies and opportunities during the transitional 1990s. These stark letters thus seem to externalize things that many people have long internalized, like desires and one’s relationship to authority. One thing that Lebedev does clearly carry with him is the aesthetic strategy he developed in the 1970s. “I felt in the 1990s that the system was changing, that we were going backwards in time. And I was ready. I already had an approach,” he said. Yet, if present-day Russia still carries many of the desires, social traumas and political links from the Soviet era, the world today is also a radically different one. Social media, global capitalism and travel, racial injustice, environmental crisis: these are just a few of the forces that are hybridizing the world, reshuffling the staid binary of East/West and exchanging putative centres and peripheries. For this reason, the one-two-punch of flipping slogans and images — which cut brilliantly deep through the ideological binaries of the Cold War era — today risks being a reductive aesthetic strategy.

For this reason, a work like ‘Fresh Air’, in which a housewife gazes out of a window into a white nothingness, feels too simple. What is this housewife seeing? Lebedev might counter that this question is the precisely the point of the work. “Art doesn’t answer questions, it asks them,” he told me. The rough black-and-white painting of Tsoi pursues that approach. Copied from a photograph of the death of Stalin, it replaces his name with that of Tsoi, exchanging one myth for another. It is a common human response in a moment of crisis to waver between laughing and crying. Lebedev’s surfaces, bright colours, and quick wordplay seem intended to expose the darkness of our cultural slipstream, but also to pull us out of them. One wonders what would happen if Lebedev took to the digital era of memes, transforming his paste-ups of paint and collage for wry snippets of pixels and headlines. “For me,” he said, “art is a kind of self-preservation. When it’s funny, it’s not scary anymore.”

Rostislav Lebedev. Between Propaganda and Frivolity

Moscow, Russia

April 13 – May 20, 2021