Premonition of Catastrophe: the art of warning by Russian-Ukrainian artist Vita Buivid

Vita Buivid was born in the Ukraine, made her artistic career in Russia and now lives in the Netherlands. For many years she has been working on projects that give political conflicts a personal dimension.

When I asked her about her national identity, Vita Buivid (b. 1962) appeared confused. “I cannot answer who I am. My mother was Ukrainian. My father was a Pole from Lithuania. I have a Russian passport, dedicated 25 years of my life to Russian culture and became a part of it!”, she confessed to me during our recent Skype conversation. The artist was born in Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnipro) in 1962 and moved to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) at the age of 28. “I dreamt about it since I was a five-year-old”, she says. In the days when the Soviet Union still existed, her story was a quite common one. Young artists from all over the country tried their best to settle in Moscow and Leningrad, lured by the rich cultural life of those cities. “I did not relocate to another country, I just moved from one city to another. And I did fit in very well. Even when I moved to Moscow later on, I was still considered a St.Petersburg artist. Nobody would have thought I was in any way connected to the Ukraine.” Nevertheless, her visual language, her habits of perception and expression were formed in the Ukraine, she admits. The vibe, the colours, the exuberance of her works belied the artist’s origins. “For St.Pete, everything in my work was over-the-top. In the 90s I added colourful hand-knitted frames to my photographs – this was considered kitsch.”

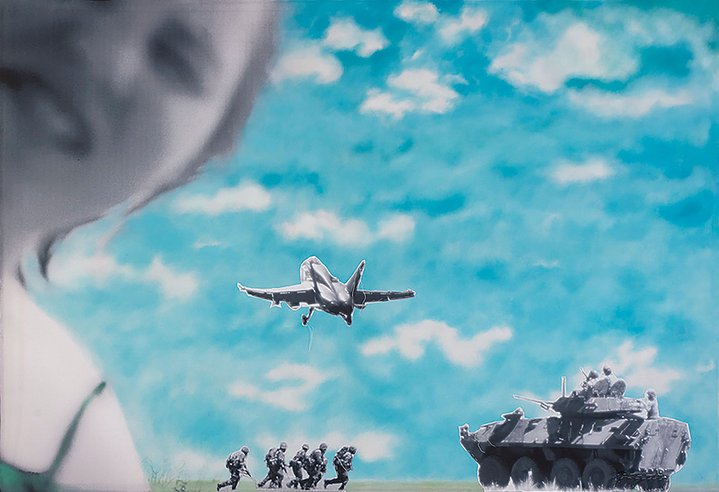

Yet, as time went by, something else surfaced in her projects, a kind of anxiety Buivid herself could not quite grasp or understand. “I don’t like to call it a premonition because it sounds crazy”, she confessed somewhat self-consciously. “But it just keeps recurring, over and over again”. It crept into the idyllic images of “How I Spent My Summer” (2008), a project that was nominated for the prestigious Kandinsky art prize. It was based on the photographs that Buivid took in a Young Pioneer camp in the Ukraine when she was just 10 years old. Back then, her father dismissed the snapshots as “nothing special”, yet the artist’s elder sister kept the negatives and gave them back to Vita many years later. “It was an utterly strange gift”, the artist recalls. She printed them out on big stretches of fabric and began to paint in oil over the prints. Then, something unexpected happened. “One day, an artist friend Gosha Ostretsov dropped by and said: ‘Stop this! It’s too beautiful. An artist should not be so obsessed by beauty’”. Buivid started thinking about this casual remark. “And then I printed out images of soldiers, helicopters and other military stuff and stitched them over these ‘beautiful’ images. God knows why. Maybe it came from the news, I don’t know”. Back then, a conflict between Russia and Georgia over Southern Ossetia broke out. The threatening images are stitched very loosely to the background so they can be removed easily. “Pull the thread and you can restore peace!”.

Then came the ‘Spy-mania’ series with lavish bouquets of flowers and James-Bond-style accessories such as cigarette cases, and sunglasses. Created in 2010, it precursed the hunt for spies and “foreign agents” that followed the mass opposition rallies of 2011-2012, when up to 100,000 Muscovites flooded the city’s streets protesting against forged parliamentary election results and Putin’s third presidential term. Buivid rarely addresses painful issues of war and peace, aggression and justice directly. She prefers to use the language of symbols and allusions instantly familiar to anyone who, like herself, spent their childhood in the USSR. Her ‘Artek’ (2014) installation evokes memories of a Young Pioneer camp in the Crimea with its dormitories emptied at the end of school vacations. Yet at the same time empty beds and rolled mattresses are reminiscent of a military barrack.

Buivid’s most heart-piercing project, an installation called Comfort Food, was created in 2014, when the Ukraine lost control over the Crimean peninsula and conflicts in the Lugansk and Donbass regions (parts of the Ukraine with predominantly Russian-speaking populations) began. “My mother’s 90th anniversary was coming. I wanted to be in Dnepropetrovsk for the birthday party, yet she kept calling me and asking me not to go. She was afraid that a train trip across the Ukraine might be dangerous for me, because of my Russian passport. Eventually, I gave in. I did not go to celebrate my mother’s 90th birthday with her.” Buivid has found a simple yet striking way to express her feelings. She bought a carton of frozen vareniki (stuffed dumplings filled with cherries) and nailed them to the wall. As they warmed up, red cherry juice began to drip down on the floor. There was a personal memory behind the bleeding dumplings. Buivid’s grandmother had a house in Dnepropetrovsk with a big cherry tree in the yard. As a child, she used to spend the summer there. “There was always an endless wait for the cherries to ripen. We waited and waited. But, finally, I was given a glass can with a rope which I could hang on my neck, and was allowed to climb the tree and pick the berries. My grandmother used them to make vareniki.” Miraculously, the installation survived for almost two months at Buivid’s solo exhibition at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art. “They kind of mummified”, the artist recalls.

Yet, time has come when no food – or other distractions – can bring her any comfort. Buivid came to the Netherlands to study at the Dutch Art Institute almost four years ago and stayed there after her graduation, and her elder sister still lives in Ukraine. Even now, she refuses to leave as she consider herself and her husband, who is recovering after chemotherapy, too old and infirm for the journey. “My sister tells me that they are better off in their apartment, it’s warm and they have some stocks of food”, Buivid says, adding that Dnepropetrovsk was not bombed as heavily as other cities but nobody knows how long this will last. She still uses the old Soviet name of the city that she remembers from her childhood. “I call them every day and they are all very depressed. This is so hard for me because there is no way to help them. They don’t want me to send them money. It’s useless because there is no money left in the cash machines over there. I am feeling totally helpless sitting here in safety, because I can’t help either my friends in the Ukraine, or my friends in Russia. But I can read news from both sides. It’s devastating.” The only people she can help at the moment are refugees from the Ukraine. Buivid, who has a good command of Ukrainian, works as a volunteer translator. “Of course they all speak Russian, but now it’s the language of the enemy for them. They are much warmer to people who speak Ukrainian,” she observes. It grieves her that many of her colleagues share the same sensibility. “It makes me sad, when Ukrainian professionals in the cultural sphere call to boycott Russians, to exclude them from cultural life everywhere. This is horrible, but they are bombed right now, so nobody can blame them for making such statements. These days it’s impossible to blame anybody for anything. We should not blame people for not going out to protest, for not doing this thing or that”.