Polshchikov as an Adept of Inhuman Perfection

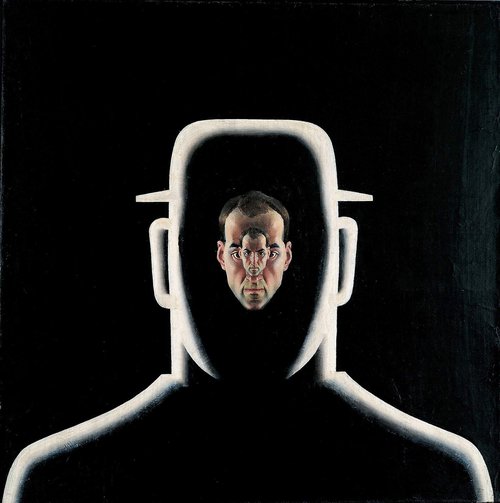

Pavel Polshchikov. Surveyor. Exhibition view. Moscow, 2025. Photo by Andrey Kazyulin. Courtesy of the artist

In ‘Surveyor’ at Moscow’s Gallery Devyatnadsat’, Pavel Polshchikov maps the terrain where geometry becomes meaning – combining gnostic symbolism with mathematical exactitude. Art critic Sergey Khachaturov traces how the artist connects object-oriented philosophy to the Soviet-era quarrel between physicists and lyricists, revealing a practice that is both conceptually charged and meticulously constructed.

Moscow’s artist-run Gallery Devyatnadsat’ (Gallery 19), known for platforming ambitious experimental work, presents Surveyor, a solo exhibition by Pavel Polshchikov (b. 1998). After my encounter with it, I concluded that Polshchikov, an adherent of ambivalence in art and life, finds himself at the crossroads of two systems. In matters of testing artistic practice using science, artist Pavel Polshchikov aligns with the principles of object-oriented art. Simultaneously, his work is a vivid continuation of the ideas of the second Soviet modernism, with the famous romantic dispute between ‘physicists and lyricists’ of the Thaw era during the 1950s and 1960s.

The exhibition resembles the backroom of a liminal network space. The gallery is located in the industrial zone of the historic Lefortovo district on the high bank of the Yauza river. A small warehouse space converted into a jewel-box gallery with a cubic room and corridor. In the room there is a round window at the top. The ceiling is slanted, on brackets. Such a mysterious ‘crooked little house’ is the perfect location for an intellectual puzzle with art objects or exhibits – ciphers, signs, clues. An enlarged copy of an ancient engraving hangs on one wall in the corridor: coiled within a triangle is the serpent-like false god Yaldabaoth with a lion's head. In Gnostic sects he is seen as the creator of the material world, who imprisoned human souls in the cages of the physical body. According to Polshchikov’s thinking, he himself locked himself into the triangle of the Euclidean plane.

Where does the title ‘surveyor’ come from? The artist explains: “In a sense, the surveyor is me, because as an artist within this project I work remotely, living in Paris, not seeing the works themselves or their final assembly in Moscow in person, and essentially also engaging in measurements, spatial design and so forth. Rooted in the surveyor’s craft – where practical geometry originates – the exhibition is dedicated to geometry as practice. And in a sense the viewer probably also becomes a surveyor. The surveyor is a character who unites, and this metaphor generally captures the essence of my project.”

Geometry and cells are fundamental concepts for this laboratory-exhibition. Guided by Proclus Diadochus’s commentaries on Euclid’s ‘Elements’, surveyor-Polshchikov establishes mobile, penetrating connections between chaos and order, the material and the incorporeal, the concrete and the abstract. A sheet with ruled squares and a hallucinogenic, infrared portrait of Hermes Trismegistus are hanging opposite the serpent-jailer of souls. It too is reproduced from an ancient treatise. The presence of the ‘Thrice-Greatest’ (Trismegistus) prophet and astrologer, who linked the pagan and Christian worlds, pleasantly liberates the imagination on themes of magic, alchemy, the secret encrypted in the obvious. From the threshold of the room one can see part of another engraving enlarged to the size of a fresco. At the top the Sun, below the Moon amongst crossed wings.

The meaning of the emblem, according to the artist: what is above, is also below. In the full version of the engraving from a 1624 treatise, Hermes Trismegistus holds a model of the celestial sphere and points to this emblem. Video screens punctuate the room. Over layers of noise, interference and footage from a rubbish tip, geometric figures and lines are inscribed. Among them is the golden-ratio spiral – after Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), the German Renaissance artist inclined to astronomical and astrological experiment – constructed from quarter-circles set within squares. It vividly demonstrates how in each cell of existence, entropy and chaos are tamed by the logic of perfect geometry. This layered shimmering space consisting of several images makes the observer’s position unstable, spectral. A follower of object-oriented theory, a reader of the works of philosophers Graham Harman, Quentin Meillassoux, Eugene Thacker, Polshchikov liberates an object beyond our comprehension from the captivity of limited logical notions about the cause-and-effect relationship of the ‘real order of things’. As with the speculative realists, space, numbers and matter escape our rational control. The game of divine order and its disappearance, not created by us, plays itself.

One might wonder with which artists Pavel Polshchikov is in dialogue? He reflects: “I wouldn’t claim any dialogue with specific artists. In hindsight, the closest affinities are Piet Mondrian and De Stijl, and Emma Kunz – set against the counterpoint of John Urho Kemp, the outsider savant of numerology and measurement.”

One object at the exhibition particularly attracted me: an office set square is leaning vertically against the wall. One side, ruled with little squares, rests on the floor. Imagine this: the length of this side of the set square matches exactly the length of the floor tile. Such an improvisation indeed seems to promise the delectable prospect of observing harmonic proportions everywhere and in everything. I recalled a scene from Bertolucci’s film ‘The Dreamers’ where the action takes place in the home of a French intellectual during the liberal revolution of 1968. A simple naive American student has come to visit him and his children. Whilst the father, resembling Barthes and Foucault, holds forth about laws and civil society, the student take out a lighter and begins to apply it to all the objects which are on the table. Everywhere there is a system of geometric relationships of parts to a whole, individual segments to a length, radius to diameter. In the end, interrupting the professor's clever speeches, the young American exclaims “isn’t this a miracle – everything, despite our will, is interconnected, subject to harmony and equilibrium!”

I thought about this film in connection with the Soviet 1960s and the romantic themes of ‘second modernism’. Perhaps inevitably, Polshchikov’s ‘Surveyor’ turns us towards this tradition as well, particularly to the debates between ‘physicists and lyricists’ of the second Soviet modernism of the Thaw era. The Constructivists of the 1920s already wanted to uncover the immutable mathematical laws in the creation of form. History remembers the Second Exhibition of the Society of Young Constructivist Artists of 1921, an exhibition which gathered together the core of the movement - the working group comprised Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958), Konstantin (Kazimir) Medunetsky (1900–1935), Vladimir (1899–1982) and Georgy Stenberg (1900–1933), and Karl Ioganson (1890–1929). The exhibition featured boldly twisted spirals, framework modules, abstract reliefs and paintings placed freely in space. Today they would be perceived as the coolest design objects, but to the young Constructivists such an association would have seemed insulting (though at that time in Russia the word ‘design’ was not yet in use).

Already in their first laboratories the Constructivists gave lessons in thinking that remain vital to this day: skills in the project assembly of time and space. Every form at the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) exhibition had a purposeful logic: there were no decorative embellishments. The tectonic properties of composition were revealed through an analytical method of working, and construction was built by principles of economy and efficiency (i.e. coefficient of performance). Alexander Rodchenko created series of forms made by the method of recursion: he traced, cut out and inserted one into the other identical figures decreasing in size towards the centre of a sheet of plywood. A three-dimensional module of such figures floated beneath the ceiling, reminiscent of alchemical emblems from engravings by the aforementioned Albrecht Dürer. The artist calculated the dynamic and static characteristics of form, its ability to hold balance, to reveal its volumetric-spatial qualities. Finally, all modules were created with the practical purpose of being useful in the national economy. The Constructivist conveyor belt of life-creation wanted to work without interruption.

In the Thaw-era 1960s, a passion for deciphering the world’s ‘wise geometry’ gripped specialists in the natural and technical sciences, many of whom were fascinated by theosophy and religious art. There was, for example, the theory of perspective developed by physicist-mechanic Boris Raushenbakh, one of the founders of Soviet space exploration. Alexander Pankin (1938–2020), a unique artist, and an architect by training fascinated by the conjugations of geometric orders of the world, and at his zenith during the Thaw era, modelled universal geometric connections within life and art. He wanted to mathematically calculate inspiration, to compute (or read) the ‘Black Square’ using Fibonacci number sequences.

In Pavel Polshchikov’s work, the reversible interplay of intuition and logos persists, though it undergoes a series of transformations. Meta-irony and speculative realism create a clear critical distance. Yet the tension between competing sign-systems for representing the world remains – held in a markedly romantic register, as if inherited from earlier generations.