Philanthropist and art collector Andrei Adamovski champions Ukrainian Art

Entrepreneur, philanthropist and art collector Andrei Adamovski was born in Bishkek in the Soviet Union, and he has lived in both Moscow and Kyiv. He spoke to Russian Art Focus about his passion for monumental sculpture and Ukrainian cultural advocacy.

A child of the Brezhnev years of stagnation yet with a flourishing artistic counterculture, during the 2000s Andrei Adamovski evolved as a collector along familiar lines. First came a love for classical 19th century Russian and Ukrainian old masters, a mix of realist and salon figurative art, the artists he had grown up seeing in museums and childhood textbooks. Then came modern art, mostly both Russian and Ukrainian. Eventually his tastes scaled up: he discovered contemporary art, fell under the Duchampean spell recognising that a work of art does not have to be something ingeniously made, but as he puts it, ‘you need only to be able to explain why it is a masterpiece’. He has an openmindedness unusual for his peer group, where there is still a strong conservativism and resistence to change in the arts, a legacy from the Soviet times, something he has overcome.

Adamovski was born in the Central Asian city of Bishkek, capital of Kyrgyzstan, a mountainous ‘stan’ with glaciers and wildlife trails in the nether reaches of the old Russian Empire, later Soviet Union, a place with breathtaking rural beauty yet a fragile economic and social infrastructure. His father was a journalist, they had books on art and literature at home and throughout his childhood he travelled a lot, visiting museums which sparked off his interest in art. He started his professional life as an applied maths teacher at Kyrgyz State University until new opportunities for private trade came with perestroika. In 1990 he moved first to Moscow then settled in Kyiv, his fortunes changed for the better throughout the 1990s when among other initiatives, he founded a telecoms company which he subsequently sold. Thereafter there was a stint in the oil business, and since 2007 he has been mostly focussed on local real estate projects in particular shopping malls. He has just turned sixty this year, and has two grown up children, Dmitry and Jacob.

By nature he strikes me as an introvert, he is mostly softly spoken and reserved, not someone who talks for the sake of it. However, he is hospitable, and art for him came naturally as a social activity: very quickly after starting to collect art he became involved in art philanthropy, it was not a gradual shift. I visited him in Kyiv in December last year when he had an exhibition of work by Victor Sydorenko (b.1953) ‘Year Zero, The Idea of Light’ at M17, a contemporary art centre he founded over a decade ago in the centre of Kyiv. It takes its name from a Soviet designed aircraft which can fly faster than the speed of sound and was once nicknamed the Mystic-A. Before visiting the art centre he invited me to his house. A vast winter garden boasting an indoor sculpture park which once was a tennis court is in the front courtyard where he exhibits works by both international and local sculptors such as Anish Kapoor (b.1954), Wolfgang Stiller (b.1961) Oleksandr Sukholit (b.1960), Zhanna Kadyrova (b.1981) and Nazar Bilyk (b.1979). As you enter this private world, you feel a bit like Alice who has eaten the biscuit and shrunk in size; there are trees interspersed with sculptures, you begin to lose a sense of normal perspective. This is a very personal vision, there is humour and fun in his choices, yet he has serious social ambitions to create a sculpture park in the centre of Kyiv. It is, he says ‘a dream’.

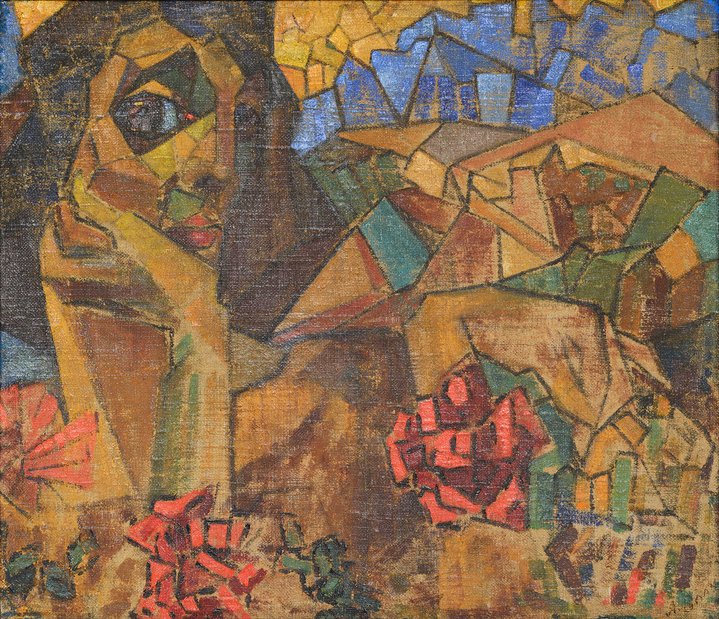

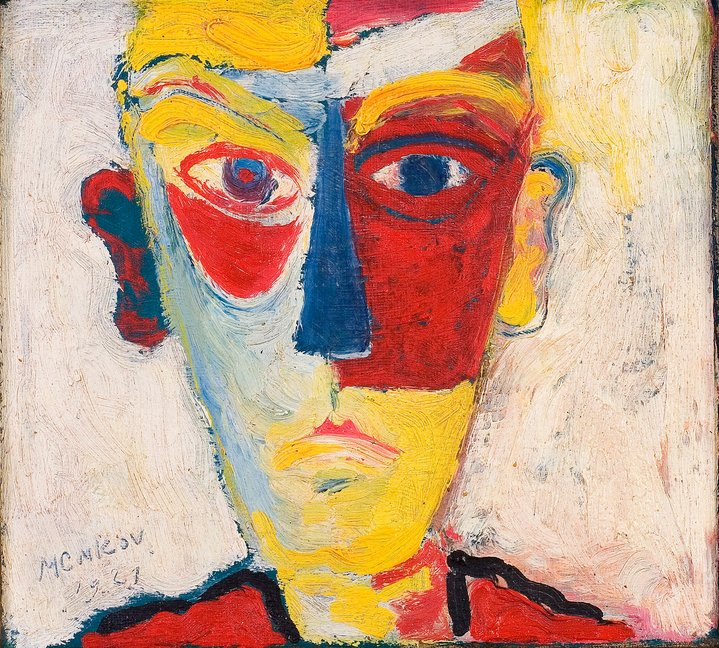

Hightlights from his art collection were shown at the Kiev National Museum of Russian Art in 2009. He has not sold off parts of his collection as his tastes have evolved and he still enjoys the classical paintings he first bought as a new collector which hang on the walls of his large Kyiv mansion, in fact he says he likes them more and more as the years pass. Indeed the centre of his house is taken over with Russian classics, large canvasses by marine painters Ivan Aivazovsky (1817–1900) and Alexei Bogoliubov (1824–1896) dominate the living and entertaining space. There are paintings by Natalia Gonchrova (1881–1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964) as well as the Ukrainian modernist artist Oleksandr Bohomazov (1880–1930). Most of them he bought from Russian auctions in London or New York, such as Yuri Pimenov’s (1903–1977) ‘Morning Washing’ painted in 1959 which he acquired at Sotheby’s in New York over a decade ago.

Athough he is no native of the Ukraine, settling there in his thirties, he has long passionately championed Ukrainian modern and contemporary art. He sees the Ukraine as a nation of highly talented, educated people where there are great artists, most of whom have only meagre support. His M17 cultural space is focussed on the education and promotion of Ukrainian art at home, the supersonic aircraft mascot behind the name tells you something of not only his ambition as an agent of social change but of the measure of the task ahead of him, it is a personal crusade. Of his space, he sees it ‘as an experimental space purposed to transform Ukrainian society through artistic processes. I believe that culture can change people and was inspired by examples of many famous collectors: Peggy Guggenheim, John Paul Getty, they all later turned from collecting to institutional activities. It is important not only to collect but to exhibit, research, communicate and educate’. The space closed indefinitely in February this year, and since then Adamovski has refocussed his energies in looking for opportunities to promote and raise funds to support Ukrainian contemporary culture abroad.

The current political situation has led to a heightened sense not only of the differences between Russian and Ukrainian cultural identity, but has brought about a need to recognise the nationality of Ukrainian artists formerly incorrectly considered Russian, a distinction Western museums and commercial art galleries and auction houses in the West have not made with any consistency or clarity until now. It is a fraught task: many of these Ukrainian artists were born in what was the Russian Empire at the time. Adamovski espouses the argument that the Ukraine’s contribution to the Avant-garde is a collective legacy that has been erased by art historians and museums. Since around 2018 with a project titled ‘Avant-garde Searching for the Fourth Dimension’ Adamovski’s activities at M17 have increasingly been focussed on the Ukrainian avant-garde as much as its contemporary artists. He sees the avant-garde as a continuing force today, the term has relevance for him: it’s a way of life, of looking at art, and for him it still embodies a real progressive and visionary attitude today.