Peter Belyi and the archaeology of the present

Peter Belyi. Photo: peterbelyi.com

The Romans invented concrete as a building material and the ruins of the Roman Empire are part of European culture. But in the work of the Russian artist Peter Belyi, this material plays a special role cementing fragments of history which are otherwise rapidly dispersing. His latest installation is a reference to Shakespeare's tragicomedy ‘The Tempest’ and in harmony with Baroque aesthetics: a restless, unstable and expressive perception of the present.

As for many Russians of his generation, Peter Belyi's (b. 1971) life has been torn into several eras. Born into the family of a famous artist in the USSR, he received a traditional Soviet art education, but then Perestroika happened, and the world changed radically. In 1993, he enrolled into Camberwell College of the Arts in London and lived in England for six years. ‘We had Tracey Emin and Paola Rego coming to lectures and it was all rather weird, but I had absolutely no appreciation for contemporary art at all. I used to go to the graphic studio early in the morning and work there all day and into the night making lithographs and engravings and it was the happiest time of my life. It coincided with a flowering of the Young British Artists, of Charles Saatchi and the Sensation exhibition. My development as an artist was not in sync with the times. I was moving at my own pace. At the time it all seemed like a sham to me….I had to re-evaluate all my previous artistic experience in Russia and learn to understand and accept other values’.

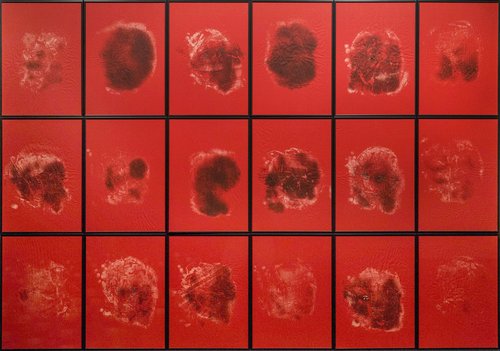

However, Belyi’s artistic career in England did begin to take shape through printmaking. The British art world also has its own characteristics in which the conservative Royal Society of Printmaking and contemporary art coexist, in parallel. ‘I started making large scale prints to understand the possibilities and abilities of printmaking. The format is a traditional limitation for this genre and that's what I started to break down: I made prints directly on the ground, using a concrete shaft. The idea was to put graphics on a par with monumental painting’. All the works were figurative and had a narrative. And it was at this point that nostalgia for his homeland, which had fallen on hard times, suddenly surfaced. Planes and ruins appeared in Bely’s drawings. ‘After all, my generation grew up on the ruins of the Soviet empire, and the poetics of ruins surrounded us, the debris of our former greatness was sticking out from every corner. It was a generational trauma incarnate’.

In 2002, Peter Belyi finally returned to Russia. It was a completely different country, where the ‘fat oil years’ had begun and a whole generation of new art institutions and private galleries had grown up. In order to find his place in this new world, he had to re-explore and understand it. ‘I went to the Guelman Gallery because I had read in a newspaper that it was the 'new Russian Gagosian'. But it didn't turn out like that, I have hardly found the basement gallery on Malaya Polyanka street and didn't even enter into any negotiations. Six months later, Marat Guelman called me himself, because he saw my graphic works. But at that time I was already making the transition from prints to three-dimensional installations’. (Marat Guelman was declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities. - Ed.)

The first installations Belyi made were connected to Soviet domestic life. They were giant towers made from mayonnaise jars which were filled with fake blood, tears, oil and water. This early project was called ‘The Dictator's Dream’ and each tower was dedicated to a historical villain such as Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini and Mao. It was a way to personally revisit and relive 20th century history.

His transition from graphics to installations was somehow gradual and unobtrusive. ‘I was deeply inspired by Ilya Kabakov. He was then at the peak of his form and fame, I saw several of his big projects in Europe. He also started out as a graphic artist, but later started using the language of installation. That is to say, like me, he had come from a rather conservative Soviet education and trauma, but he was able to convert that into a completely clear and distinct contemporary language.’ One of Peter Belyi’s early total installations, ‘The Watchman's Dream’, was clearly influenced by Ilya Kabakov, with its lyrical hero and the sense of staging. For the artist this period was important, yet ‘educational’, adding: ‘We were all self-taught in Russia, the new world of art only opened up after Perestroika’.

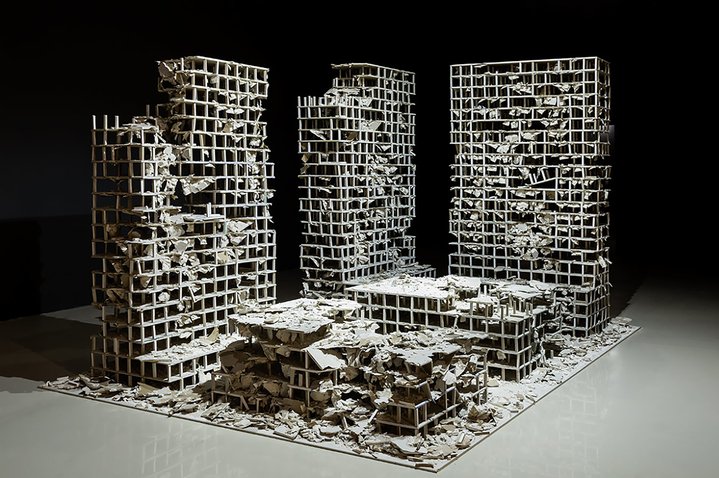

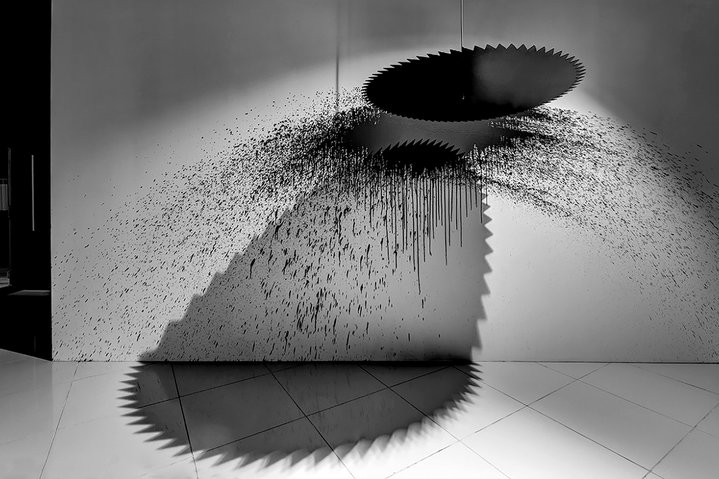

Over the past two decades Peter Belyi has made projects using the most diverse of materials: old roofing tin from houses in St. Petersburg in the ‘Unnecessary Alphabet’; he modelled architecture from found vintage slides in ‘My Neighbourhood’; he assembled the ‘Pinocchio Library’ from huge pine planks that for centuries had been languishing in old houses due to be demolished; there was the ‘Dangerous Zone’ installation built from plasterboard and then partially destroyed, the large-scale ruin of an entire city block. In 2010, Belyi received the prestigious Sergei Kuryokhin Award for his project ‘Explosion’, assembled from old, broken planks, but literally stopped time, hovering in space, somehow dynamic, yet still.

From 2010 onwards concrete started to appear in Belyi’s arsenal of materials. For many art critics and historians, this material is associated with modernism and contemporary urbanism, with angularity and brutality, but Peter Belyi somehow found a baroque nature in it. ‘It is a very charismatic but eccentric material. It took me ten years of experimentation to find what I was looking for. Concrete is a plastic material, just like clay, that has a certain shape by itself, once it is thrown on a plane. But reinforced concrete has iron hidden inside it. Unlike clay it has a strictly geometric orientation and looks like a rendering of the rays coming from an angel in a Renaissance painting. And so I understood that concrete is a baroque material. Its tectonic bubbling is in dialogue with the bubbling of clouds and water, because they are different stages of the same essence: ice, water and steam.’

Which takes us to water itself, because Belyi’s new concrete installation gurgles and overflows in rivulets of small fountains. And it is important to understand that the fountain is a special symbol in the pantheon of Soviet Culture and recreational parks. The strict asceticism and modesty in the private life of the ‘builders of communism’ contrasted with the baroque excesses of public areas, such as so-called culture parks or underground metro stations (which looked more like underground palaces). Later, flowerbeds and fountains even reached residential areas, but during perestroika it all fell apart and abandoned megaliths of the past became commonplace. And now, in Belyi’s installations, they have came to life again, in a traumatised form. ‘The fountain is a symbol of urban melancholy and infinity. It's well known that you can look at flowing water endlessly. It is known that the magnetism of flowing water is an endless flowing, and a kind of stupor in which a person looking at the moving water masses slows or stops time. But it is just as important to me to show a viewer how the ordinary and inconspicuous can reveal its aesthetic potential. You think, as a result, 'I used to walk past that every day and never noticed it!’

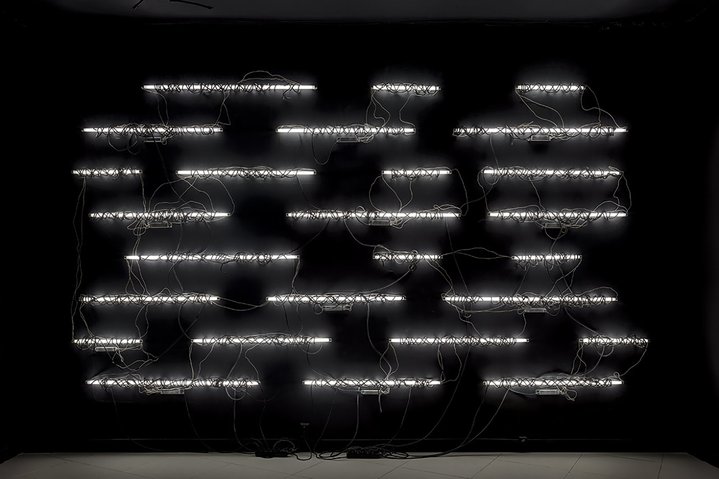

This new project has a similarly baroque structure yet its made of simple elements including concrete, iron barrels, fountains and the sound of flowing water. It is an exuberant installation, yet minimalistic, just like Italian post-war Arte Povera objects, which Russian people understand well and to which they feel a natural affinity. But here there is an additional element. After a long time of working exclusively with objects, Peter Belyi has come back to conventional ‘painting’, creating large-format monotypes, rolled on an etching press. These monotypes are suspended in space, visible from both sides and positioned as sculptures. There is hypnotism in the black colour with its large range of grey tones. His monotypes keep all the hallmarks of graphic art, painting and sculpture, but what dominates is experimentation with materials and techniques to invent new methods of hand printing on a large scale. In the end, the untrained viewer still believes that ‘an artist is someone who paints pictures’. Here although conservatism seems to be rewarded, the untrained viewer actually falls into a trap.

Everything moves in spirals and the current exhibition project, The Tempest, curated by well-known St. Petersburg artist and curator Alexander Dashevsky (b. 1980), is also connected to the notion of a spiral. You see a spiral both in the graphics of a poster design, and as an object in the exhibition. On closer inspection you see that this object is made literally using one sole gesture: a car tyre is cut and unfurled in the form of an S-shaped spiral, and inside it there is a gurgling fountain. The artist saw an everyday functional object with a story, altered it just a little and this object turned into an artwork, rich with meanings. It is as if the viewer, already having accepted the ‘painting’, has to accept that too.

As the artist explains, ‘My artistic DNA is minimalism. This approach came to me originally as a kind of adolescent protest against excess. The language of Soviet and Russian art is quite obscure. We don't have a lot of artists who express themselves clearly and distinctly. So Arte Povera and American minimalism are very important to me as a methodology, as something to keep in mind all the time, as an ability to speak in an extremely concentrated way. How does the baroque coexist with minimalism? I always hold onto minimalism as a measure, a kind of gold standard that allows you to remove all unnecessary things and get to the heart of an idea. Because there is always the danger of getting carried away with the material and drowning in it. To create extra tension, I invited the curator Alexander Dashevsky, whose creative method is diametrically opposed to mine. As an artist he likes theatricalisation and builds spectacular installations made out of works by other artists. My exhibition approach is totally different, but I find it interesting that a person with such a powerful antithesis appears in the project. Here it was the theatrical baroque that was important, rather than a minimalist, carefully calibrated asceticism. As a result, the work opens up to a wider audience, because the language I want to speak is quite complex. The viewer in Russia still doesn't like minimalism and asceticism’.

Peter Belyi’s latest exhibition opens at a challenging time for Russian art and culture in general. Many artists have fallen into a state of inactivity and depression, and many art critics believe that in the prevailing conditions exhibitions are impossible. In response to this, William Shakespeare, one of the true great connoisseurs of the human soul, already long ago gave us his advice:

‘There be some sports are painful, and their labor

Delight in them sets off; some kinds of baseness

Are nobly undergone; and most poor matters

Point to rich ends.‘

But we can also find answers to the predicament of the present in old native folk wisdom: ‘Sow your rye, even if you are about to die’. Yes, today these are tragic circumstances, but we are not derivative of our circumstances, we can think about and change our circumstances. As Peter Belyi says: ‘For the last six months we have all been in a state of shock, and in my case, the reaction was not apathy, but incredible artistic intensity. I started making new work and maybe it wouldn't have happened if we hadn't experienced such an emotional shake-up. It's like dealing with the death of a loved one, when the shock is so strong that you emerge from the experience completely changed. And in order to save yourself, you have to keep doing what you can and are able to do, there are no other tools.’

The Tempest. A solo exhibition of Peter Belyi

St. Petersburg, Russia

September 8 – October 29, 2022