Pavel Otdelnov: future ruins

A Russian artist glimpses history in the making by exploring the country’s ugly side – from toxic industrial wastelands to city landfills.

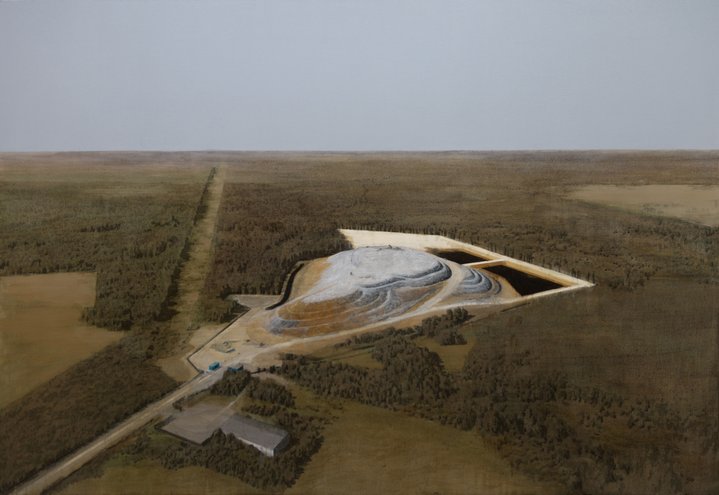

Seen from high above, a massive, sculpted ziggurat rises out of the dense pine forest that stretches to the horizon. At first glance, clean, architectural lines in this work ‘Landfill Alexandrov’ by Russian artist Pavel Otdelnov, almost mask the fact that the towering mass is simply tonnes of garbage, packed into a landfill site.

But the other painting in his exhibit for this year’s Moscow Biennale zooms in on the same landfill and here it’s an uncompromising, hyper-real view, showing a cluster of dump trucks lost in a vast sea of rubbish. In ‘Landfill Timokhovo’ flecks of coloured plastic give way to an unnatural grey-on-grey horizon of flattened garbage that is entirely man-made. It’s a chilling vision, but one that reflects one of the most hotly-debated issues in Russia today: how to dispose of the waste generated by its new consumer society. Otdelnov joins that debate in his latest work. He filmed an investigation into where his own trash went after he threw it away, producing an 18-minute video ‘The Trash Trip’, which plays alongside his paintings in the new wing of Moscow’s State Tretyakov Gallery, as part of the current Biennale.

The artist attached GPS satellite trackers to his garbage; one was stuffed inside an old bread roll, another encased in bubble wrap and a third placed in a discarded soap box. Otdelnov charts their progress with cool detachment. He narrates in matter-of fact style as we see the flashing GPS signal travel from his courtyard trash container to the waste plant where workers sort rubbish by hand (selecting only about 10 percent for recycling) and finally to the landfill in a forest over 200 km from Moscow. It’s a personal story, but one Otdelnov scales up with devastating effect. “As an ordinary person, a citizen, I live here in Russia and I do this each day,” Otdelnov told Russian Art Focus. “Near me, there are a million people, doing exactly the same thing without really thinking about it.”

Following local protests in 2018 against the noxious effects of waste sites around outer Moscow, city authorities began transporting trash further afield to neighbouring regions and even as far as the Archangelsk one in Northwest Russia.

When residents of Shiyes, a village in a region located over 1,100 km from Moscow, discovered plans to locate a new landfill on their doorstep, they set up a protest camp to stop construction of the facility, which is due to process 500,000 tonnes of the capital’s waste each year. Local officials, eager to fulfil orders from the capital, called in security groups and there were sporadic clashes with local activists as plans for the dump went ahead. It’s a sensitive topic for the Kremlin as the strategy of exporting rubbish seems also to have exported protests to these new locations. The plight of Shiyes has struck a chord with ordinary Russians and thousands of people across the northwest joined protests this summer.

“Of course, it’s awful and I completely sympathise with those people who are protesting against this landfill site,” Otdelnov said. He watched intently during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s annual call-in this year, expecting a response to the Shiyes garbage protests, but none came. “He avoided it because it’s not a popular subject,” Otdelnov said. “Besides, I think he supports building a landfill in Shiyes. That’s why he didn’t talk about it.”

Reflecting on past political power is familiar territory for Otdelnov, whose haunting landscapes often reflect the breakup of the Soviet Empire and Russia’s search for a new social and economic path. But this is the first time he has made an artistic intervention into a live political controversy. In Russia, this carries a degree of risk.

Otdelnov says this step into “social consciousness” was important for his development as an artist. He points to a politically-engaged art tradition in Russia, from the 19th century ‘Peredvizhniki’, who staged mobile exhibitions “for the people” outside Moscow and St. Petersburg, to the revolutionary art of 20th century Avant-Garde. But he claims he is not worried about repercussions, because his aesthetic treats the personal experience of ordinary Russians with a sense of distance, thereby removing it from everyday politics. It’s a balance between detachment and personal involvement which he seeks in all his work.

“I look at what is going on as a person on the inside and as if I am also at one remove… as if it was another civilisation, not the one I am part of,” Otdelnov explains. “To me it’s important to have that viewpoint. Art makes this perspective possible.”

Art critic Ari Akkermans says the work on show at the Moscow Biennale marks him as “one of the emerging voices in contemporary Russian art”. He argues that Otdelnov’s brand of “melancholy realism” is right on trend, as global contemporary art rediscovers figurative painting. “Otdelnov represents a kind of renewal of figurative painting… something unseen in Eastern Europe for a long time, where it’s usually conceptual/abstract art that leads, followed by a kind of ironic realism… His paintings are not just historical scenes, but have a very emotional connection. It’s a personal story,” Akkerman argues.

Earlier this year, in a solo show with the title “Promzona” at Moscow’s Museum of Modern Art, Otdelnov dug deep into his own personal history and that of the city where he grew up. Born into a Soviet-era ‘labour dynasty’, Otdelnov drew on stories of his family, three generations of engineers who worked at highly polluted chemical factories of Dzerzhinsk, to examine what he described as “the ruins of a Soviet mythology”.

In ‘Promzona’ (which translates as “Industrial Zone”), Otdelnov’s huge, photographically-precise canvases showed the now abandoned factories where his family once worked, interspersed with everyday objects and stories of their lives. His exploration of Russia’s Soviet industrial past shows how its mythology failed to translate into reality for the ordinary people working in often dangerous and toxic environments. And yet growing up in Dzerzhinsk, Otdelnov says he felt it was an optimistic place. Born in 1979, just over a decade before the Soviet Union collapsed, he traces his first exposure to art to his father, who would often illustrate explanations of how science worked. “He would tell me stories and draw them. He showed me how to put out a fire; he made drawings of how big machines worked,” Otdelnov recalls. He remembers, too, how his grandfather tried to direct Otdelnov’s early artistic career. He disapproved of young Pavel’s dark comic-book illustrations and would buy him brightly-decorated colouring books. Pavel didn’t take the bait and simply coloured the drawings in black.

“He was fighting against the blackness, he wanted my drawing to be more optimistic, but it didn’t work,” says Otdelnov, remembering how offended he was when his grandfather found another use for his dark drawings. Those were the days when toilet tissue was in short supply in Soviet households, Otdelnov chuckles.

Today he says he is ready to leave the ruins of Russia’s Soviet past behind, to look further at the “present-day ruins” of landfill sites being constructed every day at huge speeds. It’s history in the making, on a human scale. The story of our civilisation will be told by archaeologists of the future, sifting through these sites to piece together a picture of people’s lives through the garbage they threw away, Otdelnov explains. “It’s a way of looking at history so you can touch it… offering not the big narrative, or big historical concepts, but reflecting history through your own reality.”

Promzona project by Pavel Otdelnov: online version

Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art

Moscow, Russia

31 October 2019 – 22 January 2020