Olga Kisseleva: deciphering the talk of trees

This eco-minded Russian artist living in France has created a ‘social network’ for plants, while working on projects that verge on art, as well as scientific research bordering on science fiction.

Olga Kisseleva’s (b. 1965) conversion to contemporary art happened when she was still a student. It took place in one of the storerooms of the Hermitage Museum, the former Winter Palace of the Russian Tsars in St. Petersburg. She was then studying at the city’s Vera Mukhina Higher School of Art and Design, which could not afford to even buy a slide projector. Because of that, some lectures took place in the palace’s vaults, where students accessed the paintings stored there. Kisseleva was particularly fascinated by the way her teachers could decipher the meaning of a Flemish still life by interpreting the objects represented in it. They were, in fact, symbols, often even moral warnings. A toppled goblet could, for instance, symbolize life’s impermanence and so on.

Although she was fascinated by painting, it was not her element. Soon after she graduated, Kisseleva developed an unstoppable interest in less traditional media. She was instead more attracted to a medium which used a language that was less elitist, such as the one of computers and other analogue or digital devices. She continued her studies, developing step by step her signature approach that sees the artist in constant dialogue with the scientist and the technician.

Her first mark was a pioneering book she wrote about video and computer art. In 1999, she founded and directed the first Art & Science programme at the Art Department of the Sorbonne University in Paris.

Her keyword is “Ecology”, but for her, that term goes far beyond taking care of nature. It implies instead an analysis of the complex ways how various species, including human beings, cooperate and compete. Issues of social equality and the way business and political interests manipulate people’s lives, both directly and indirectly, are often the topic of her artistic research.

In the past few years, Olga has been busy building her own Garden of EDEN, an acronym that stands for Ethical Durable Ecology Nature. It is an international project, which investigates the way vegetal species communicate between each other, as well as with other species. It all started with the death in 2010 of a 14th century elm tree in the southwestern French seaside resort of Biscarrosse, 40 km from Bordeaux. That tree was one of the victims of Dutch Elm Disease.

For more than 600 years, that very elm had each spring budded white flowers in the shape of a wreath. According to a local tradition, this strange phenomenon proved the innocence of a young shepherd girl who died under that tree of a broken heart, after the prince to whom she had been engaged to rejected her when evil tongues told him, on his return from a war, that she had been unfaithful. Attempts to grow a new elm from the sprouts of the one that had died all failed.

However, three years later, the town municipal council invited Kisseleva to create a tribute to the dead tree. They expected some sort of sculpture. What they received instead was a miracle. The artist got in touch with France’s National Institute of Agricultural Research and managed to crossbreed the sprouts of the original tree with a Siberian elm, whose great merit is that is does not get infected by the fungus causing that disease.

When the young tree blossomed for the first time, it was obvious it bore no relation to a Siberian elm, but the flowers which were once again white and once again they also sprouted in the form of a wreath.

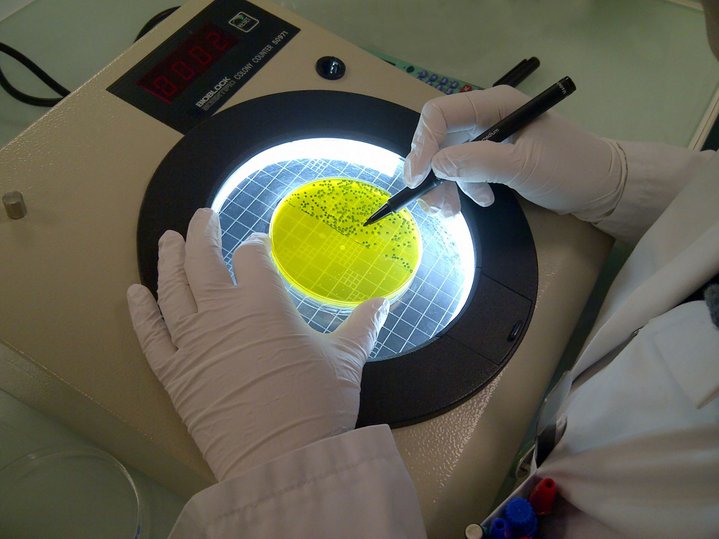

Kisseleva spent a great deal of her time and energy in developing EDEN and learning the language of the plants. Counting on the help of visionary scientists and technicians, she learned that trees can communicate in many different ways, for example, they make sounds and produce different types of gas. They can even change the thickness and form of their trunk. In other words, they can speak. The speed of their communication, however, is much slower than that of a human being. The tree takes half a day to utter a single word. According to Kisseleva, a tree can teach a fallen one how to stand again. This is what spurred Kisseleva and her team to develop a social network for trees that allows trees planted in different corners of the planet to communicate through specially designed and engineered technology.

EDEN has been shown in many countries across the globe. In February 2021, it will make its debut in Australia, as a part of a group exhibition called ‘Tree Story’ at the Monash University Museum of Art in Melbourne.

Kisseleva has strong and radical views about how art should be used.

“Biennales and museums should not be perceived as a mausoleum, or a Mount Olympus. Neither getting a work of art shown at a biennale, nor preserving it in a museum improves the world. To me these places are artistic (infra)structures, the equivalent of a laboratory, that allow you to explore the world around you, conduct experiments and create functional prototypes, the most successful of which can, in one form or another, get out of this artistic world and move into our everyday life,” is how she puts it.