Oleg Tselkov: don't believe, don't fear, don't plead

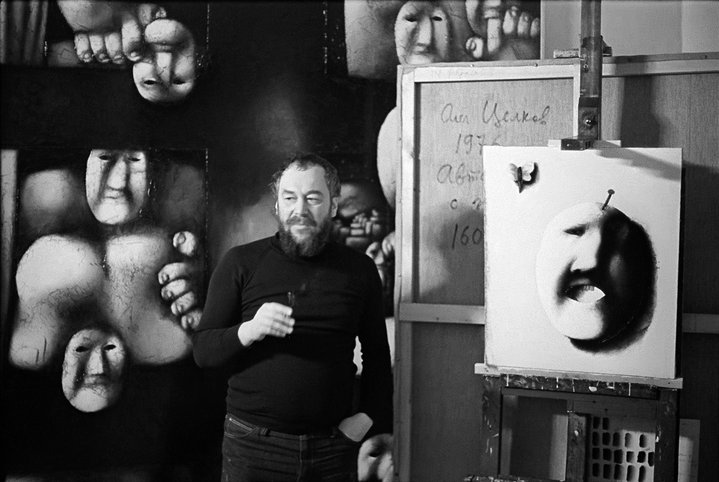

As a friend of the late Oleg Tselkov and an admirer of his work, art collector Igor Tsukanov writes on the life of this artist whose haunting, colourful figurative paintings continue to challenge us. A major retrospective opens at MMOMA this March.

Oleg Tselkov (1934–2021) became interested in drawing as a child. Despite his lack of basic training, at the age of fifteen, this self-taught artist was awarded a place at the famous Moscow Art School. The originality of the young man’s talent was obvious. Later, Tselkov said that it was at that point, in the late 1940s, that the basic principles of his creativity were developed in relation to the free form and bright colours of his images. After finishing art school, in the 1950s, he twice tried to continue his education in art institutes, but was thrown out both times. His art and his behaviour were too unusual for academic institutions. As a result, Tselkov received his higher education at the Leningrad Institute of Theatre and Music, where he trained as a set designer. Having created a number of sets for the theatre, he devoted himself to painting, gradually finding his theme and developing his artistic method.

In the 1950s, Tselkov made a whole series of works in the aesthetic of the Russian avant-garde, but no more than fifteen have been preserved. He put the rest in an enormous sack and submerged them in the Moscow River, considering them to be imitations. Two wonderful examples of Tselkov’s avant-garde works are ‘Matador and Bull’ (1957) and ‘Two Women’ (1958). Even in these paintings, brutal colour prevails in Tselkov’s palette. There are no subtle tones and transitions.

In the summer of 1960, there was a breakthrough in his work — Tselkov created ‘Portrait’, a painting with two faces. “It was a revelation,” admitted the artist. “I saw the image in a dream and, in the morning, I started work. For the first time (and I was the first), I accidentally ‘pulled away’ from the face which is ‘in the image and likeness’ and revealed a FACE. I was absolutely astonished… in it were imprinted the millions of years lived by humankind, as if I was in a dark room feeling the walls, the wardrobe, the bed and suddenly found the door handle. I opened the door and saw the light.” The artist was sure that he had turned his own page in the history of art. “As fate would have it, I was the first artist to create a face in which there is no idealisation. A face in which there is no trace of the likeness of God.”

Soon, Tselkov would bring together his characters into a single type reminiscent of his own face: rounded, with a snub nose, narrow eyes and a bald head. The first such type appeared in ‘Portrait with a Flower’ (1962) and was reinforced in the legendary ‘Group Portrait with a Watermelon’ (1963). In his memoirs, poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko recalled: “When, in 1964, in the studio of artist Oleg Tselkov, I showed [well-known American playwright] Arthur Miller the manuscript of my poem ‘Bratsk Station’, dotted with the red pencil of the censor, he was amazed. How is it possible to write in such circumstances? Who are the people that torment you this way? I pointed to Tselkov’s painting, in which self-satisfied creatures were using knives to hack at the living body of a cut watermelon.” Miller thought for a while and then, without negotiating, bought the work for an unprecedented price that Tselkov came up with at random.

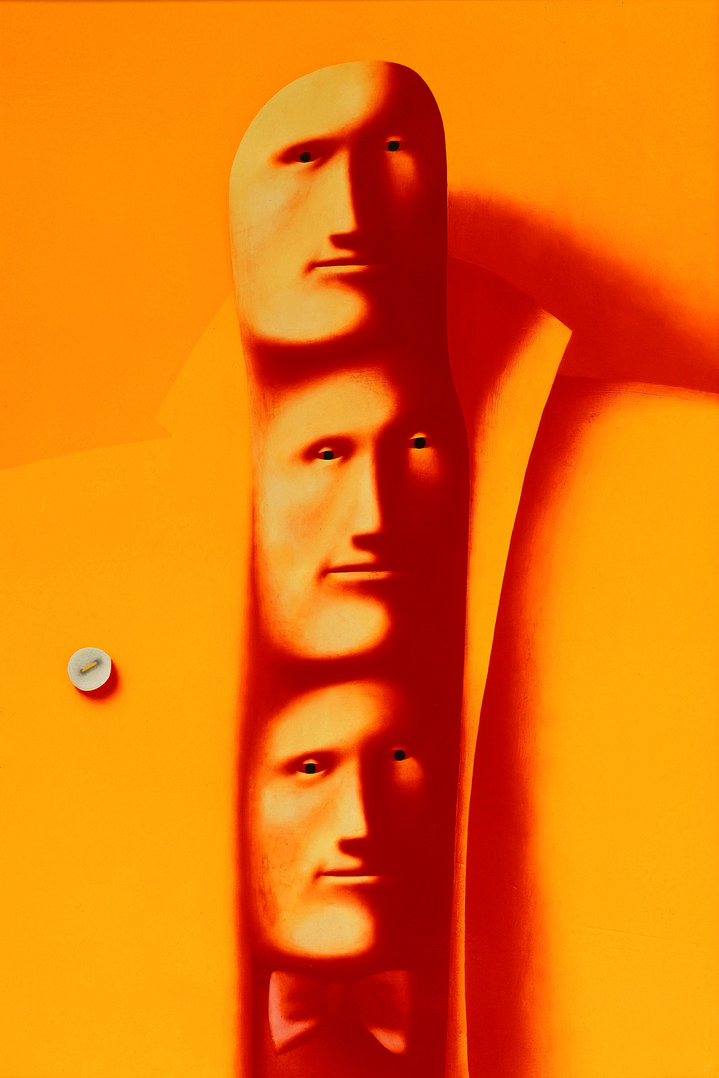

Tselkov dedicated the next 60 years of his career to his character. The details varied: the subject of the paintings changed, the palette evolved, the dimensions grew dramatically. In emigration, from the end of the 1970s, the artist began to introduce surrealist motifs into his canvases, creating multi-headed or multi-eyed figures, or figures with a head between their legs or with a nail or a safety pin in their head. But, the basic theme remained unchanged: the study of the other side of the human personality, which includes egotism, anger and melancholy. The image of a man alone with himself.

Tselkov admitted that his characters were born of the high concentration of evil that surrounded him in the USSR, but he categorically denied that the images he created were caricatures of the transformation of Soviet people into homunculi. “I don’t have any concrete problems with a single person, but I do have a very concrete problem with the mass of people who put each other down, torment each other and kill each other. I have the right to have that problem with the past, the present and the future.” In his works, the artist expresses his rejection of the society of “little people”, who exist in every time period, and the way of life they create. They are static, wooden and, like their way of life, eternal and this makes them truly frightening. Erik Bulatov notes that “there is no satire in Oleg Tselkov’s paintings. He says nothing about the time or the place where they live. They have a different nature, it’s about physiology. They are the result of that dreadful, dark origin that is hidden in the soul of every person. A literary analogy would be Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The eponymous hero Jekyll sets loose his innermost conscious and subconscious desires incarnated in the form of Mr Hyde. However, Hyde turns out to embody neither light nor beauty, as Jekyll hoped, but rather vileness and evil”.

The dominant theme can be found in different periods and a whole range of compositional and colouristic resolutions. In the 1960s, Tselkov surrounded his “tribe as yet unprecedented” with sets, drapes and flowers. From the 1970s, his compositions became simplified and only single objects remained: a knife, a button, a glass, a pear, a candle, a shovel, an axe, a guitar and so on. Tselkov’s bright colour palette also changed. In his portrait series, vibrating fiery red shades began to take precedence (Self-Portrait with Rembrandt on our Birthday, July 15, 1971). The forms became more rounded and smooth and graduated transitions appeared. The work with colour became more complex. In the 1980s and later, Tselkov completely rejected mixing colours on the canvas and began to use no more than two or three basic spectral colours (red, yellow, green, violet). By employing intense scumbling he achieved a new depth of colour. As in the works of the old masters, a particular internal light emerges from his canvases, one that cannot be captured by the camera’s lens. Often, the artist creates on the canvas a disharmony of colour combinations (violet and green, for example), taken to a visual extreme. The viewer becomes absorbed in the colour of his paintings, as if in a special airy element that is transformed into painterly flesh.

In numerous interviews Tselkov denied that his predecessors or contemporaries had any influence on his work. “I never had a favourite teacher or an authority… I dreamed this all up myself,” he liked to stress. But, in conversations about art, he admitted that he liked Malevich’s late works, the bodily forms in Rubens’s paintings and the chiaroscuro of Rembrandt’s canvases. He was relatively knowledgeable about the works of Fernand Léger, Francis Bacon and Diego Rivera. He instinctively sensed a connection to the lonely genius Vincent Van Gogh. For me, the artist’s creative testament is the work ‘Five Faces’ (1980). He placed his characters in an undefined space, from which they look at us in a phosphorescent light like envoys from space or from eternity, asking the unexpressed question: “Who are you and why are you here?” Oleg Tselkov, who felt that he was “not from here, a stranger”, sought answers to these questions his whole life and sent from afar ‘a tribe as yet unprecedented’, which we and future generations must come to know.